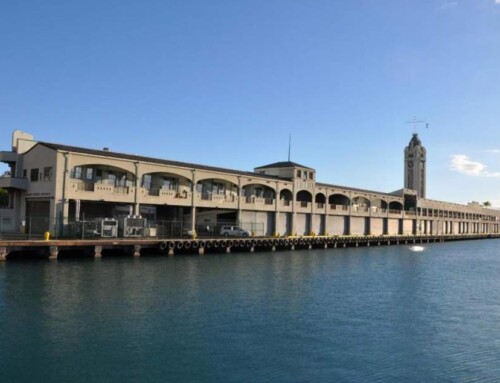

The Natatorium is back in the news as the newest addition to the National Trust for Historic Preservation’s list of “National Treasures”. Trust executive staff is in town this week to launch the campaign. Read the full story from the Star Advertiser below.

Click here to read more about the history of the Natatorium.

National treasure

A long-suffering landmark receives added recognition, renewing debate over what to do with the historic site

By Allison Schaefers

Honolulu Star Advertiser, May 21, 2014

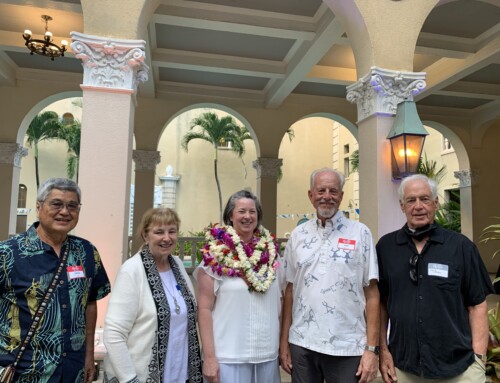

A nearly three-decade battle to preserve the neglected Waikiki War Memorial Natatorium is getting added ammunition from the National Trust for Historic Preservation, which is adding the landmark to its list of “national treasures” — a move that harnesses the support of thousands of preservationists from coast to coast.

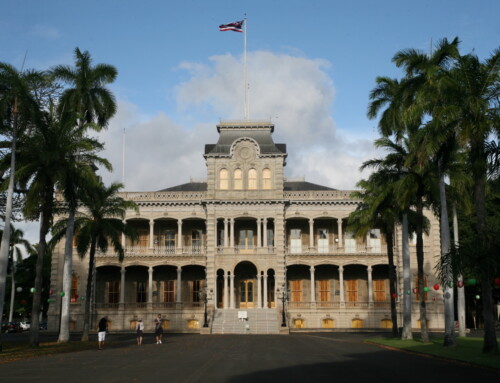

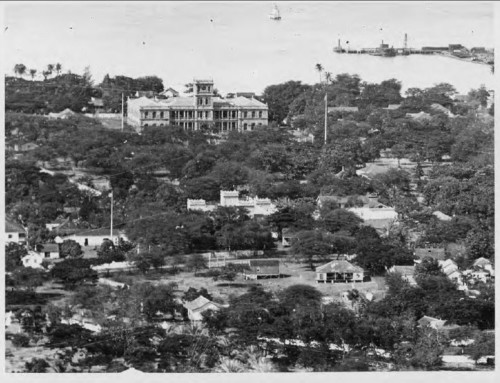

Built in 1927, the Natatorium’s memorial arches, 100-meter saltwater pool and stadium bleachers were meant to honor Hawaii’s 10,000 World War I veterans. It has been recognized as an architectural landmark on the National Register of Historic Places and for a few generations was the place where Hawaii residents learned to swim and great watermen like Olympic medalist Duke Kahanamoku and his contemporaries trained. However, those glory days ended in 1979 when the Natatorium was closed due to disrepair.

The trust’s new campaign aims to present alternatives to an $18.4 million plan announced in May 2013 by Gov. Neil Abercrombie and Mayor Kirk Caldwell to demolish the pool and bleachers and develop a public memorial beach at the site, said David J. Brown, the National Trust’s executive vice president, who plans to announce the designation in Honolulu on Wednesday.

“The Natatorium is an important war memorial from a period that Hawaii has lost a lot of its history. … It really has the opportunity to be the place that continues to honor the service of WWI veterans,” he said. “We think a restored Natatorium could once again become a place of recreation, recuperation and reflection.”

Caldwell and Abercrombie have said their plan would be better for the community than spending the estimated $69.4 million it would take to fully restore the memorial.

AT A GLANCE

Waikiki War Memorial Natatorium

>> Built in 1927 to honor Hawaii men and women who served in World War I

>> Consists of a 100-meter saltwater pool, stadium bleachers and Beaux Arts arches

>> After decades of debate, Gov. Neil Abercrombie and Mayor Kirk Caldwell joined forces last year to announce plans to demolish the crumbling pool and stadium, replace them with a public beach and move the arches inland.

The Natatorium is the latest on a list of about 45 historically significant places that the trust has made a commitment to preserving in the three years since it began its National Treasures Campaign, which secured $2 million from program partner American Express. “We started the program about three years ago as a way to go deeper and provide more time and staff resources and sometimes financial resources to endangered places,” Brown said.

Success stories for trust treasures include Colorado’s Chimney Rock Archaeological Area and Paterson, N.J.’s Hinchcliffe Stadium, one of the few remaining Negro League ballparks, he said. In 2012 President Barack Obama established Chimney Rock as a national monument, and the trust’s efforts at Hinchcliffe recently attracted about 700 volunteers who spent a day shoring up the stadium.

By channeling preservation experts and philanthropists nationwide, Brown said, the trust’s treasures have an improved chance of securing government money, grants and private funding. “We almost always can come in and provide a small-size grant to provide planning help and then work on major fundraising to help local groups expand their community of potential donors,” Brown said.

The nonprofit preservationist group Friends of the Natatorium began advocating for the historic structure’s restoration in 1986 and had seemed to gain traction in 1995 when the trust listed the structure as one of America’s 11 Most Endangered Historic Places. The designation, which does not have as much teeth as the latest one, led to a partial $4 million restoration by then-Mayor Jeremy Harris.

However, more recently the trust’s efforts had become something of an uphill battle as more key decision-makers in Hawaii came to see the crumbling monument as a safety hazard, whose rust-covered walls blighted Waikiki’s shoreline.

Eighty-eight-year-old Fred Wong said he’s optimistic that the new designation will be equally benefical to the Natatorium, which is where he learned to swim as an 8-year-old in 1934 and where he watched exhibitions of his classmate Bill Smith, who later went on to win two Olympic medals.

“We made special memories there,” Wong said, adding that his understanding of the Natatorium’s significance deepened after he spent seven years in the military.

Wong, who has shared his thoughts about the Natatorium in an oral-history video project that will soon be posted on YouTube, said any plan to dismantle the memorial is disrespectful to the veterans whom the Hawaii Territorial leaders sought to honor.

“They wanted to do something really big,” he said. “Now we say that was 100 years ago, we can forget about them. … It’s very much like digging up a grave.”

But Rick Bernstein, who heads the Kaimana Beach Coalition, cautions against getting swept up in the “good old days.” Bernstein estimates that the coalition has been supporting a new beach as a replacement for the “failed Natatorium structure” for the past 25 years.

“We have supported this change because the only alternative in redevelopment of the Natatorium would be a complete demolition of the structure. City engineers estimate that rebuilding it from the ground up would cost in excess of $70 million, and it would necessitate commercialization of the structure to pay for the phenomenal amount of maintenance required to operate a saltwater pool in the ocean if they could even get a permit,” Bernstein said. “The other alternative would be to let the structure continue to cave into the ocean, which would be a risk to life and to the environment.”

He said the coalition wants to see the Abercrombie and Caldwell plan, based on the recommendation of the city-sponsored 2009 Waikiki Natatorium Task Force, move forward. “Making it a memorial beach rather than a memorial swimming pool is the right thing to do for the people and for the ocean,” he said.

In May 2013, Caldwell and Abercrombie proposed razing the swimming pool and bleachers to create open beach space, and moving the arches inland.

City Director of Design and Construction Chris Takashige said Tuesday that Caldwell will wait for the results of the plan’s draft environmental statement, which is slated to be completed before the end of 2015, to determine whether the beach expansion plan is the appropriate path forward.

In a statement Tuesday, Abercrombie said, “We are working and coordinating with the mayor, his administration and the City Council to resolve all outstanding issues with the Natatorium as we wait for the results of the environmental impact statement.”

NATATORIUM TIMELINE

1896: Sanford B. Dole deeds land where the Natatorium now sits to William G. Irwin.

1919: Hawaii’s territorial government buys land for $200,000 from the W.G. Irwin Estate for a memorial park to honor isle residents who served in World War I.

1921: Territorial Legislature authorizes Territorial War Memorial Commission and $250,000 in bonds to build the memorial.

1922: Commission chooses design submitted by Lewis Hobart of San Francisco.

1927: Opening ceremonies include Duke Kaha?na?moku making the inaugural swim.

1949: Natatorium renovated by territorial government for $82,000.

1972: Army Corps of Engineers releases draft environmental statement recommending demolition of Natatorium.

1973: Natatorium placed on Hawaii Register of Historic Places. State Supreme Court rules that demolition of the Natatorium would be an “illegal act.”

1989: City Council mandates that the Department of Parks and Recreation operate the Wai?kiki War Memorial Natatorium.

1998: Funding of $11.5 million provided by the city for restoration of the Natatorium.

1999: The Kaimana Beach Coalition sues the city and the state Department of Health to have the Natatorium classified a “public swimming pool,” requiring a permit from the Health Department. Judge Gail Nakatani grants the plaintiffs’ request, and a restraining order is issued to the city to halt all restoration until a permit is issued. Circuit Judge Gary Won Bae Chang lifts the restraining order and says the city has received all necessary permits for the land portions of the restoration. Work on the pool section remains halted.

2000: The restoration of Phase I is completed.

2002: Final Health Department rules for obtaining permits for saltwater pools go into effect.

2004: City proceeds with $6 million emergency repair of the pool walls. Engineering study concludes that sea walls and decking of the Natatorium are at risk of collapse but that the bleacher structure is in good condition.

2005: Mayor Mufi Hannemann stops all work on the Natatorium.

2006: City orders a study of alternatives for the site.

2009: Waikiki Natatorium Task Force recommends demolition of the Natatorium and construction of a beach.

2013: Gov. Neil Abercrombie and Mayor Kirk Caldwell announce partner??ship to develop a public memorial beach at the Natatorium, including tearing down the pool, relocating the archway and creating a new beach in place of the pool and stadium.

Sources: National Trust for Historic Preservation, Star-Advertiser

____________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Historic Hawaii Foundation 1974~2014 ~ Celebrating 40 years of preservation in Hawaii!

We’re Social! Like us on Facebook Follow us on Twitter

Sign up for our E-news for the latest on preservation-related events, news and issues here in Hawai‘i & beyond.