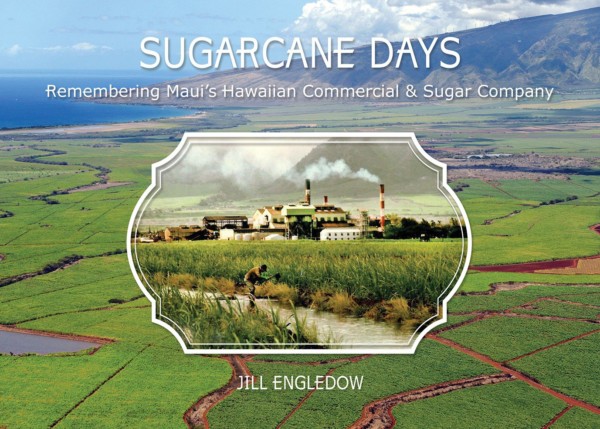

The musing below by Jill Engledow captures the wistful nostalgia of the plantation era and its end. Jill’s recent book, “Sugarcane Days: Remembering Maui’s Hawaiian Commercial & Sugar Company”, is the recipient of a 2017 Honor Award for Achievements in Interpretive Media.

Green cane still grows on fields left fallow by the closing of Hawaiian Commercial & Sugar Co., the last sugar plantation in the Islands. Winter rains have kept the ratoon crop alive on some 36,000 acres of the great plantation begun in the 1870s by Samuel T. Alexander and Henry P. Baldwin and their rival, Claus Spreckels.

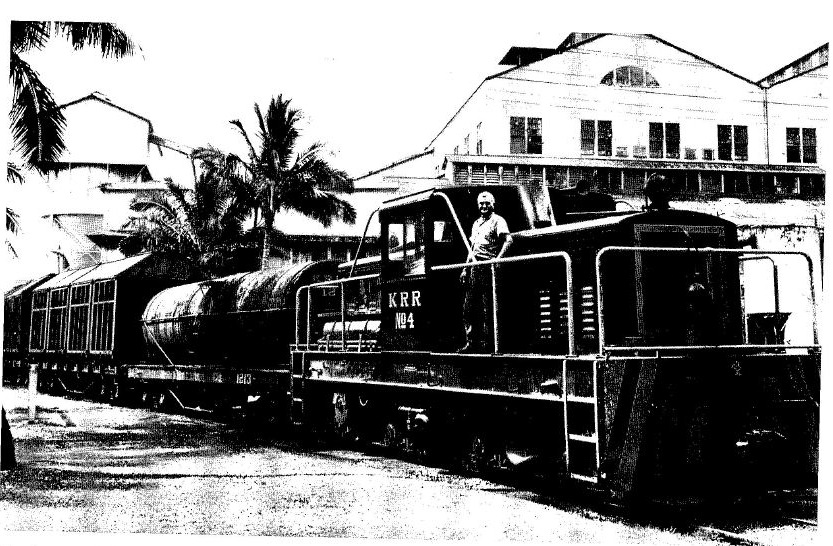

But the old mill is still, its tall stacks no longer sending out the plumes of smoke that acted as a weather vane for generations of Central Maui residents. Six hundred laid-off workers are figuring out what to do with the rest of their lives. Alongside a cane-field road, a couple of out-of-work Tournahaulers stand idle, their chain-net sides examples of the ingenuity of generations of plantation workers who shaped tools and processes to meet their needs. That ingenuity helped keep this plantation in business longer than any other, despite financial losses and ongoing community conflict over cane smoke and the control of water from mountain streams.

Other remnants remain of the plantation life that ruled this island and its neighbors for nearly two centuries–an old market, church buildings, a school, a pool, a post office. Here and there in the fields, a stand of trees memorializes the site of a camp, a village where workers lived, and just down the road is busy Kahului, the town the plantation built to replace those camps.

Across from the mill, two old houses remain, home to the Alexander & Baldwin Sugar Museum. The main building contains displays about the industry that was the engine of Hawaii life for so long, with the house next door acting as an archive. In the museum’s files are thousands of photographs, particularly from the years 1948 to 1968, many taken for the in-house newspaper, the HC&S Breeze. They illustrate the glory days of plantation life, when labor organizing had raised wages, opportunities dreamed of by hard-working immigrant ancestors were bearing fruit, and children benefited from a community that filled their days with activities, education and entertainment.

One picture in particular tells a story. Half a dozen youngsters in shiny new clothes surround HC&S community coordinator (and future Maui Mayor) Hannibal Tavares, each holding a prize won in a “declamatory” contest. Seeing these smiling youngsters reminds one that many of their ancestors arrived poor but ambitious to do dusty and difficult labor in the fields, perhaps never becoming fluent in the language in which their grandchildren would memorize and recite famous speeches. In a few generations of hard work, these families had produced offspring who would go off to university and come home to run Hawaii.

No wonder people of that generation feel such nostalgia for plantation life, for a childhood lived in villages where they ran barefoot, where neighbors shared, and where it seemed sugar would always power Hawaii. Now those children, growing old, mourn the last harvest and wait with the rest of us to see what new crops can be found to fill the fallow fields.

Jill Engledow is an award-winning journalist and author who has lived on Maui since 1968. A former reporter and copy editor at the Maui News, Jill is now a free-lance writer living in Kihei, with a special interest in Hawaiian history. She recently published two new books. Sugarcane Days: Remembering Maui’s Hawaiian Commercial & Sugar Company is a nostalgic picture book featuring images from the company’s in-house newspaper, the HC&S Breeze, from 1948 to 1968. The Story of Lahaina is a short but comprehensive history of the town that has survived and thrived through every era of Hawaii history. It also includes vintage photos.