The Historic Hawaii Foundation Annual Meeting held at Aloha Tower Marketplace on May 11, 2016 was steeped in harbor history. Members were treated to a special presentation and “quiz” about Honolulu Harbor by writer Bob Sigall after which Bruce McEwan, President of Friends of Falls of Clyde, provided an update on preservation efforts for “Falls of Clyde” currently docked at the Harbor. Below, HHF volunteer writer Kristen Pedersen provides a backdrop of harbor history.

Honolulu Harbor: A Brief Overview by Kristen Pedersen

In 1793, when Captain William Brown directed his sailing ship, Butterworth, into what is now known as Honolulu Harbor, he couldn’t have known the influence the harbor would have on the future of the island. Although the crew called it Brown’s Harbor, the captain decided to name the harbor Fair Haven. It eventually became Honolulu Harbor, which is a rough translation of ‘protected bay.’

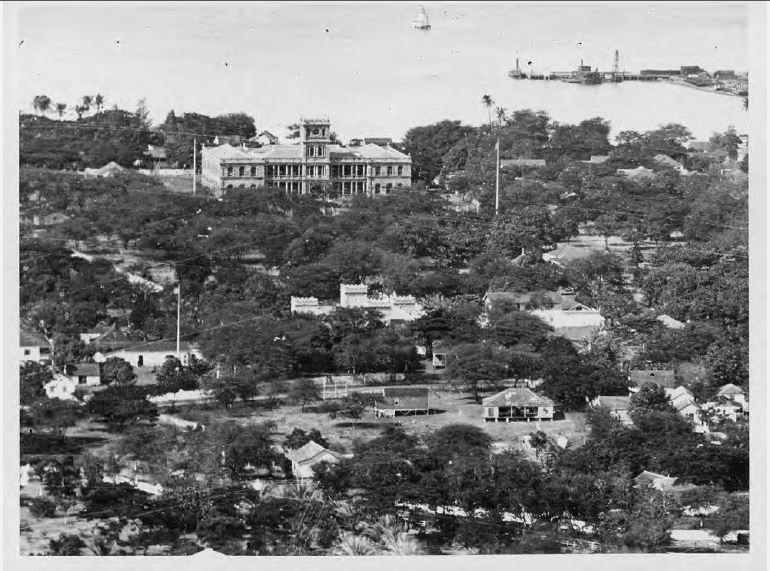

Even then, it was clear that the bay offered an excellent place for large ships to set anchor, and as more trade ships followed in the next few years, a town began to grow up around it. In 1809, in response to the rapid growth of the harbor area and the increase of trade ships docking in the bay, King Kamehameha moved his Waikiki residence closer to the harbor. His goal was to tighten control on the valuable sandalwood trade flowing through the islands at that time.

By the 1820s, whaling ships began to stop at Honolulu Harbor. Shops and businesses such as sail-makers, boarding houses, blacksmiths, laundries, and bakeries were built to support the new industry, and residential neighborhoods for the business owners followed shortly after. The town of Honolulu was growing rapidly, due in large part to the whaling industry as shipping traffic in general continued to increase. Change has been one constant in the life of the harbor, and it came again in the late 1800’s when the shipping focus shifted from whaling to sugar and pineapple products. With more demand for Hawaiian sugar and pineapple, plantations expanded and the need for plantation workers also increased. People from across Asia and Europe arrived to work in the fields, all traveling through Honolulu Harbor. Many of the plantation workers would fulfill their obligations on the farms, then move to urban Honolulu to take advantage of the job opportunities there or start their own businesses.

At this point in history, the harbor was still full of sailing ships, but steam power was on its way, bringing shorter trans-Pacific travel time, more goods and products, and tourists from the U.S. west coast. It was not surprising when the plantation economy was joined in the early 1920’s by the tourism industry. It was common to see cruise ships finding berths in piers next to cargo ships being loaded and unloaded with goods going in and out of Hawaii. The content of the ships was changing, but the effects were the same – more growth and expansion for Honolulu.

Until airplanes began regularly flying to Hawaii, ships were the only way to get everything and everyone to and from the islands. They were also one of the few connections to the outside world for island residents, so when a ship arrived in the harbor, it was news. Hawaii’s newspapers reported the shipping news daily, including details about the cargo, the ships’ timetables, and incoming and outgoing passenger lists. Honolulu Harbor was of primary importance in daily life for decades.

The most recognizable landmark of Honolulu Harbor is the Aloha Tower. The Aloha Tower opened in 1926 after five years of construction, for an enormous cost of $160,000 (over $2 million today). Located at Pier 9, it has continued to operate since 1926, welcoming ships from around the world to Honolulu. It is ten stories high with a 40 ft. flag mast on top. For about forty years Aloha Tower was the tallest building in Hawaii. It remains one of our most charming landmarks and is also on the National Register of Historic Places. By the time Aloha Tower was completed and dedicated, Oahu was already becoming a popular vacation destination for wealthy families. In the 1920’s and 1930’s Matson steam ships docked at the base of the Tower and passengers were greeted with lei, Hawaiian music, and hula. After the attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941, the Tower was painted in camouflage colors so it would be difficult to see at night, and Coast Guardsmen from the USCGC Taney were stationed around the base of the Tower to protect it from potential attack. In addition to the Tower’s paint job, another major alteration to the Harbor occurred in the early 1940’s with the construction of the Nimitz Highway. It was built to serve the military bases and the Honolulu airport during World War II, and it made land transport in and out of the harbor faster and easier.

Today, Honolulu Harbor is administered by the Hawaii State Department of Transportation Harbors Division. It is still an incredibly important part of life in Hawaii as over 80% of our goods are imported. This equates to roughly 11 million tons of cargo every year. People are also still arriving on Oahu through Honolulu Harbor, but now they are on cruise ships instead of sailing ships or steam frigates. Annually, there are approximately 260,000 cruise ship visitors and they spend around $220 million dollars a year in the local economy. Honolulu Harbor is instrumental in the growth, vibrancy, and prosperity of Hawaii, and has been since the arrival of the first sailing ship in 1793.

Click here to view Honolulu Harbor History – A Photo Essay *

(*Mahalo to Matson Archives & the Hawaii State Archives for the photos & Historic Hawaii Foundation volunteer, John Williams, for creating the slide show.)

Kristen Pedersen is a professor in Public Communication at Portland State University. Prior to finishing her PhD, she worked in film and television in Miami, Los Angeles, and Brussels, Belgium. She is a U.S. Coast Guard veteran, an avid researcher, and from a kama’aina family.

Source Material

2014 Annual Visitor Research Report. Hawaii Tourism Authority. Web. 16 June 2016.

http://files.hawaii.gov/dbedt/visitor/visitor-research/2014-annual-visitor.pdf

Aloha Tower. Aloha Tower Marketplace: A Community Revitalization Project. Web. 16 June 2016. http://www.alohatower.com/aloha-tower/index.html

Burlingame, Burl. Aloha Tower: Past and Present. Star Bulletin, 17 August 2003. Web. 16 June 2016. http://archives.starbulletin.com/2003/08/17/features/index1.html

Honolulu Harbor. Hawaii Department of Transportation. Web. 14 June 2016.

http://hidot.hawaii.gov/harbors/files/2012/10/Honolulu-Harbor-Oahu.pdf

Honolulu Harbor. World Port Source. Web. 14 June 2016.

http://www.worldportsource.com/ports/review/USA_Honolulu_Harbor_Oahu_166.php

Kim, Alice. Shipping News. Hawaii Digital Newspaper Project. Web. 18 June 2016.

https://sites.google.com/a/hawaii.edu/ndnp-hawaii/Home/historical-feature-articles/shipping-news

Mak, James. Creating “Paradise of the Pacific”: How Tourism Began in Hawaii. UHERO Working Paper NO. 2015-1, 3 February 2015.

http://www.uhero.hawaii.edu/assets/WP_2015-1.pdf

Spoehr, Alexander. A 19th Century Chapter in Hawaii’s Maritime History. The Hawaiian Journal of History, vol. 22 (1988).

https://evols.library.manoa.hawaii.edu/bitstream/10524/255/2/JL22078.pdf

Thompson, Erwin N. Pacific Ocean Engineers: History of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers in the Pacific, 1905-1980. USGPO: Washington DC, 1985.

https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/011390308

Whaling Industry. Hawaiihistory.org. Web. 18 June 2016.

http://www.hawaiihistory.org/index.cfm?fuseaction=ig.page&PageID=287

Wiegel, Robert L. Waikiki Beach, Oahu, Hawaii: History of its Transformation From a Natural to an Urban Shore. Shore & Beach, 76:2, Spring 2008.

http://dlnr.hawaii.gov/occl/files/2013/08/Wiegel-2008-ShoreAndBeach-Waikiki-history.pdf