Defending the National Environmental Policy Act

August 29, 2020 Sharee Williamson, Senior Associate General Counsel at the National Trust for Historic Preservation

This story was originally published on the National Trust for Historic Preservation’s Preservation Leadership Forum with different images. You can read the original piece here.

Today, the National Trust for Historic Preservation and a coalition of partners filed a lawsuit challenging new National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) regulations issued earlier this month. Signed into law on January 1, 1970, Congress established NEPA to ensure that federal agencies consider the impacts of their actions on the human environment, including both cultural and natural resources. Like the National Historic Preservation Act, NEPA is a procedural statute intended to foster well-informed federal decisions that minimize harm. The new regulations undermine this congressional mandate and severely weaken one of the nation’s strongest environmental laws.

In February, the White House’s Council on Environmental Quality (CEQ) issued a draft of the new regulations. Despite receiving over 1 million public comments expressing concerns about the draft rule, the final regulations are substantially the same as the draft. Some of the most troubling changes in the new regulations are those that make public participation more difficult, give project applicants more control over which alternatives are reviewed, and remove the requirement that federal agencies consider indirect and cumulative impacts, including climate change impacts, when making decisions.

Kalaupapa National Park on Moloka‘i (National Park Service)

CEQ’s purported reason for the rule changes is to remove administrative red tape that allegedly slows down infrastructure improvements and to ensure a “more efficient, timely, and effective NEPA process.” However, expert reports studying the reason for the slow development of some highways and other infrastructure projects have concluded that NEPA is not a significant contributor to delays. Instead, issues like lack of funding and lack of consensus are often the culprit. The new regulations do nothing to address these issues.

Honolulu Rapid Transit (Federal Transit Authority), photo AL Pelerini.

Instead, the new regulations will inject confusion into the regulatory process, which is likely to spur litigation as agencies work to apply these hastily adopted rules. Also, some agencies, such as the National Park Service and the Advisory Council on Historic Preservation, have agency-specific NEPA regulations or guidance that are consistent with the previous regulatory scheme. It is expected that agencies will begin the process of updating these materials to comply with CEQ’s new rules, which will lead to additional confusion and delay.

While the legal challenge to the new regulations will take time to work through the courts, the effective date for their implementation is September 14, 2020. The new regulations also include language that allows agencies to begin applying them immediately to projects where NEPA review is already in progress. This means that historic preservation advocates participating in NEPA reviews will need to take steps now to adapt their approaches to ensure that impacts to historic resources are fully considered.

One major area of concern under the new rules is that agencies may not provide adequate information to the public about upcoming projects, because more projects will be excluded from NEPA review altogether. Any information that is supplied may be less comprehensive, even for projects where NEPA review is still required. As a result, it will be important to be proactive in identifying projects that may have impacts to historic resources. Formal public records requests may be needed more often. Contacting agency personnel directly to learn more about project development may also be helpful.

Advocates should also prepare to encourage agencies to ensure that their decisions comply with NEPA’s statutory mandates by meeting the standards of the old regulations. For example, if a federal agency declines to review a project under NEPA that previously would have been subject to review, advocates can go on record with the agency noting that the new regulations are contrary to NEPA’s statutory text and are currently being challenged in court. Additionally, advocates should be ready to point out that other laws—such as the National Historic Preservation Act or state and local NEPA-like laws—are still in effect.

While the legality of the new NEPA regulations will ultimately be decided by the courts, there is another interesting possible wild card that could result in their revocation. The Congressional Review Act (CRA), passed in 1996, provides Congress with enhanced oversight authority over federal agency rulemaking. It includes a lookback provision that allows a new session of Congress to revoke any regulations issued by agencies during the final 60 working days of the previous Congress. In addition to the CRA, some members of Congress have already proposed including an amendment in currently pending legislation that would prevent federal agencies from implementing the new NEPA regulations. However, given the uncertainty regarding any congressional solution, and the harm that the new NEPA regulations could cause to historic resources beginning immediately, the National Trust will diligently work to overturn the new regulations in the courts.

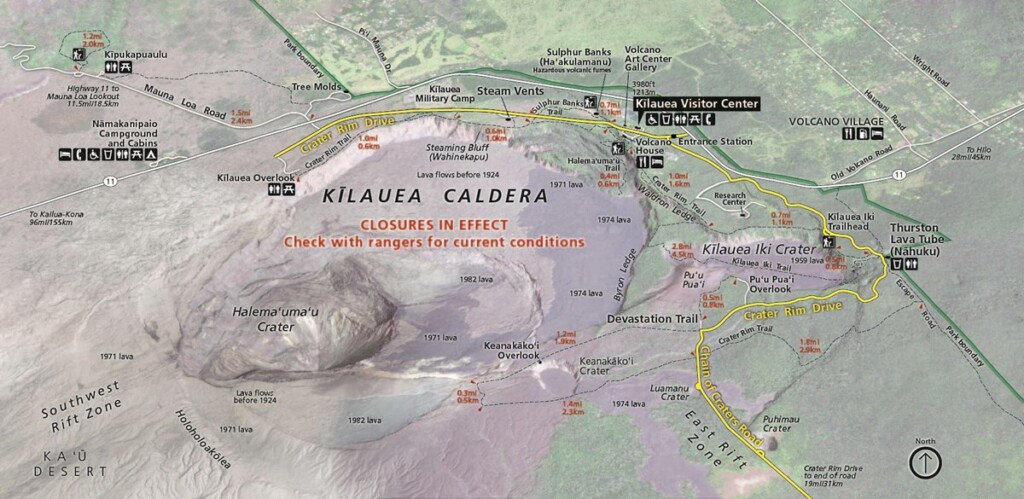

Volcanoes National Park Eruption Recovery (National Park Service)

9/4/20 Update: There have been a total of four lawsuits filed, challenging the NEPA regulations. The National Trust’s was filed in Charlottesville, Virginia, led by the Southern Environmental Law Center, with a coalition of 16 organizations. Another coalition of 13 groups, led by Earthjustice and the Western Environmental Law Center, filed suit in San Francisco. And a third coalition of 9 organizations, led by Natural Resources Defense Council, filed suit in New York. That case has an emphasis on environmental justice. More recently, on August 28 a group of 21 state attorneys general (not including Hawai‘i) filed a lawsuit in San Francisco. None of the other cases have filed for injunctions. A group of nine industry organizations (e.g., Chamber of Commerce, American Petroleum Institute, etc.) has now intervened as defendants in all the cases. On August 25, the Department of Justice and the industry groups filed motions to dismiss NTHP and partners’ lawsuit. A court hearing for a preliminary injunction motion was scheduled to be held today and we are awaiting the results.

Examples of recent federally-funded or managed projects in Hawai‘i that required NEPA reviews include:

- Ala Wai Watershed Flood Control (Army Corps of Engineers)

- Honolulu Rapid Transit (Federal Transit Authority)

- Off Shore Wind Development (Bureau of Ocean and Energy Management)

- Undersea Energy Cable (Department of Energy)

- Queen Ka‘ahumanu Highway (Federal Highway Administration)

- Homeland Defense Radar (Missile Defense Agency)

- Volcanoes National Park Eruption Recovery (National Park Service)

- National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific Visitor Center (Veterans Affairs)

- Military Training at Pohakuloa Training Area and Mākua (U.S. Army)