The encroaching ocean

Two historic places on the Big Island are at risk, a national report says

By Marcel Honoré

Honolulu Star Advertiser, 5/20/14

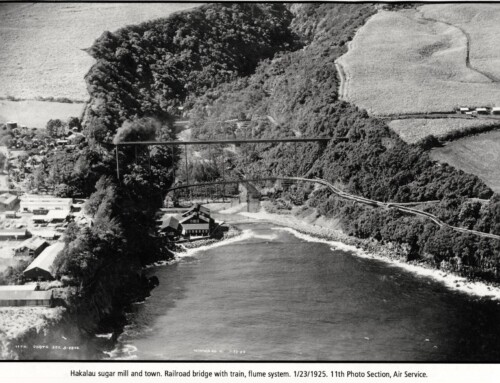

In Alaska, artifacts that show how native peoples first crossed into America from Siberia are jeopardized as the sea ice that protects those ancient objects melts and exposes them to ocean waves.

In Virginia the first permanent English colony in America is in danger of being submerged by severe storm surge.

And in Hawaii two sacred coastal sites that reveal the ingenuity of how the islands’ kupuna once lived and thrived are now threatened by advancing seawater and pounding surf.

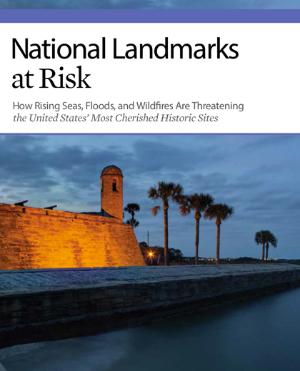

A new report out Tuesday from the Union of Concerned Scientists highlights these and 26 other U.S. historic places put in serious peril by rising seas, fiercer wildfire seasons and other impacts linked to man-made climate change.

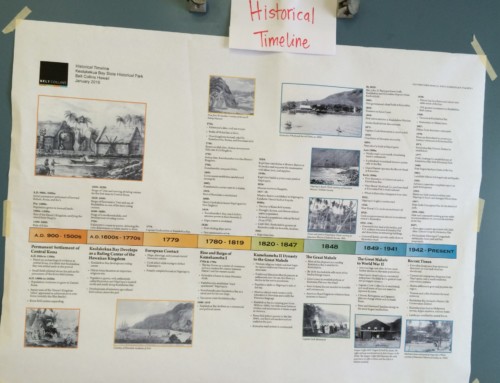

The two Hawaii sites that the report spotlights are national historical parks on Hawaii island’s west coast: Pu‘uhonua o Honaunau and Kaloko-Honokohau.

“For Native Hawaiians these kind of places can’t be restored. They’re gone, they’re gone forever,” said Fred Keakaokalani Cachola, a Native Hawaiian who helped lead the push to make Kaloko-Honokohau a national historical park in the 1970s.

“It’s not just a loss of place; it’s a loss of who we are. How do you measure a loss of that?” Cachola added.

The UCS report is the first of its kind on such sites, representatives of the Massachusetts-based nonprofit say. Other reports, such as those from the International Panel on Climate Change and the U.S. National Climate Assessment, warn of the serious problems ahead due to a warming earth. However, none of them have sections dedicated to these historic sites and resources, said Adam Markham, UCS’ special initiative on climate impacts director.

“They’re places that people care about,” Markham said of the 30 sites that UCS selected. “They tell the story of American history, and if they disappear they cannot be replaced.”

They’re also places, Markham added, where there’s strong scientific data available to chronicle the environmental changes taking place primarily due to man-made emissions.

All but four are in coastal areas that UCS lists as vulnerable to sea rise and stronger storm surge from warming ocean waters.

Sea level has risen about 8 inches globally in the past century, and the rate of rise is speeding up, Markham said.

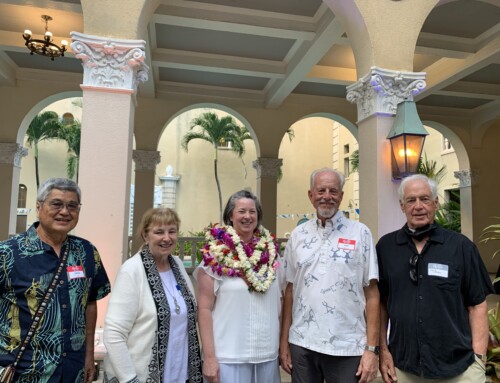

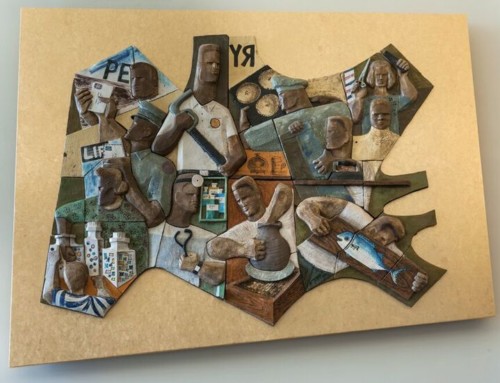

CESAR LAURE / SPECIAL TO THE HONOLULU STAR-ADVERTISER

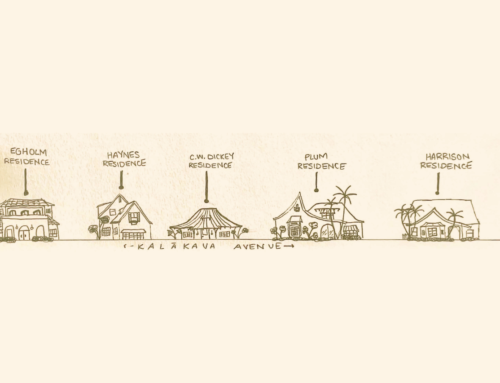

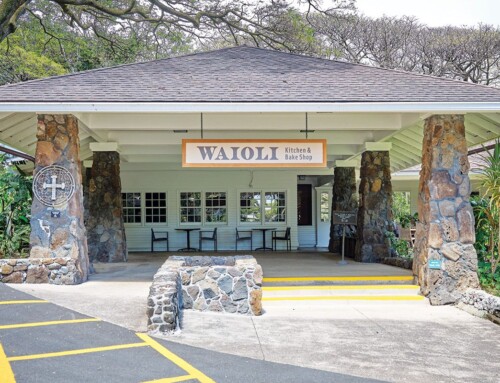

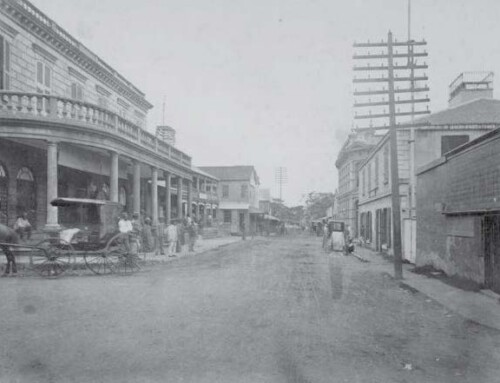

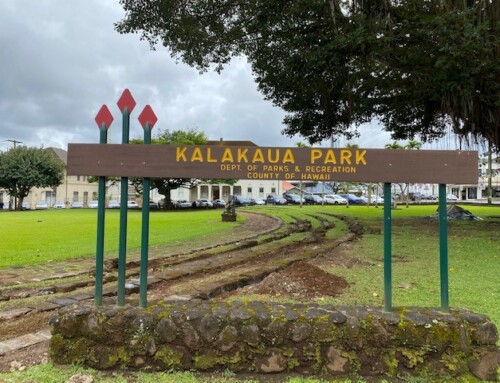

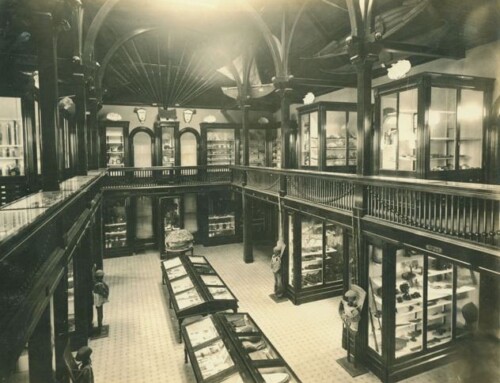

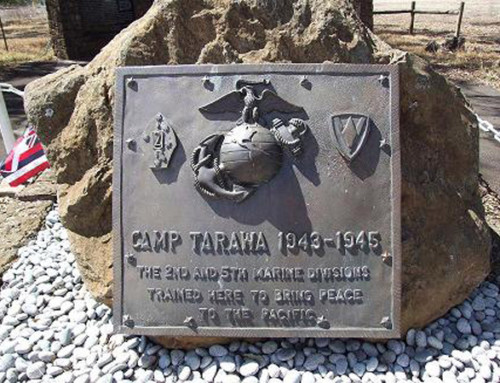

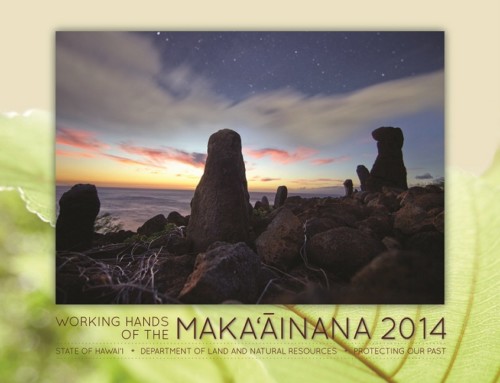

1. KALOKO-HONOKOHAU NATIONAL HISTORICAL PARK

Once a thriving Hawaiian settlement, it includes three traditional areas for trapping and raising fish.

>> Acres: 1,160

>> Park established: Nov. 10, 1978

Kaloko-Honokohau includes three traditional areas for trapping and raising fish: the Kaloko fishpond (which features a centuries-old restored kuapa, or fishpond wall), the ‘Aimakapa fishpond and the ‘Ai‘opio fish trap, officials say. Park staff aims to eventually restore the ponds so that they might conduct seasonal fish harvests there using traditional practices, Cachola said. Historical accounts also identify the park as a possible site where the bones of Kamehameha I were hidden, he added.

“There is the spirit of our kupuna there,” Cahola said. “We are not just restoring a place; we are restoring a process of human harmony with the environment.”

But the park’s staff, along with its community and advisory groups, think climate change is damaging the resources there, Cachola said. “The constant pounding on that wall is creating almost daily repair work,” he said.

The National Park Service recently completed a study that examines climate change’s threats to Kaloko, Markham said. NPS officials were unavailable Monday to discuss that study or any other efforts to mitigate the impacts to Kaloko and Pu‘uhonua o Honaunau.

Also, a U.S. Geological Survey study is due out in the coming months that examines the freshwater levels at Kaloko, said Kari Kiser, a senior programmer with the National Parks Conservation Association, a nonprofit group that serves as a watchdog for the National Park Service. The ponds there rely on a careful balance of sea and fresh water flows, Kiser and other say.

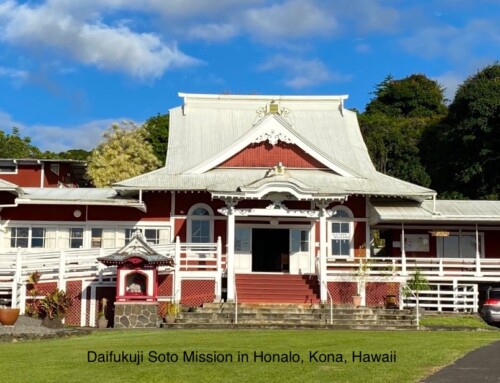

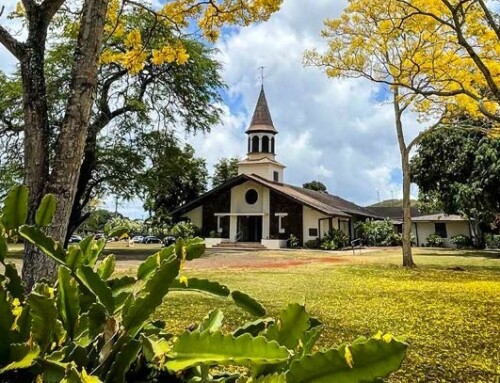

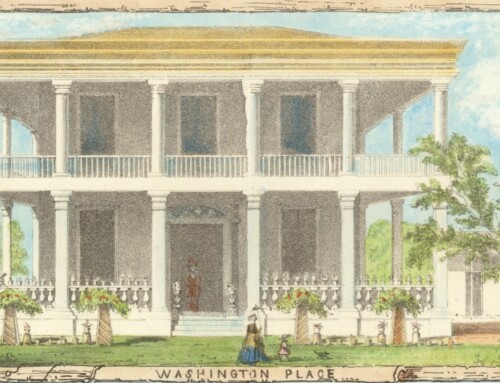

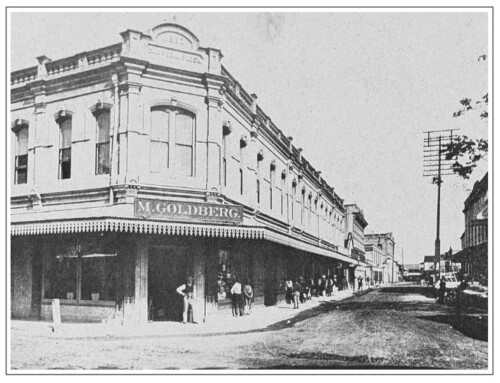

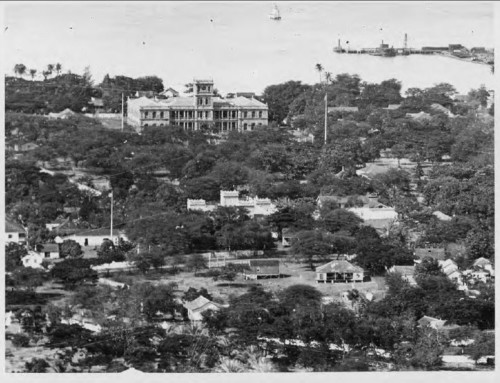

Pu‘uhonua o Honaunau once served as a site where Hawaiians who violated the local kapu (sacred laws) could go for rehabilitation, Cachola said. The UCS report further described a puuhonua generally as “a wartime place of refuge, where noncombatants and defeated warriors alike could find sanctuary.”

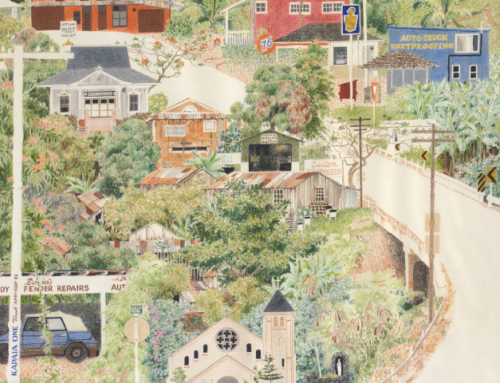

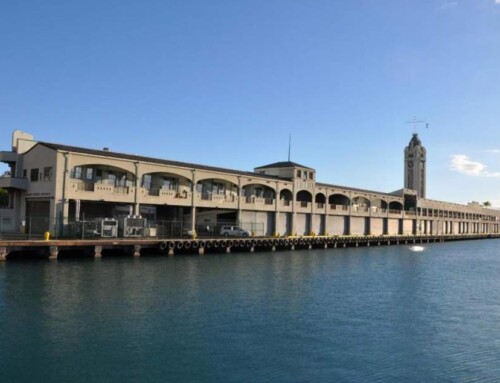

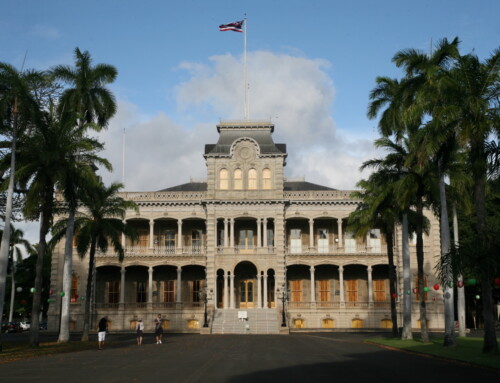

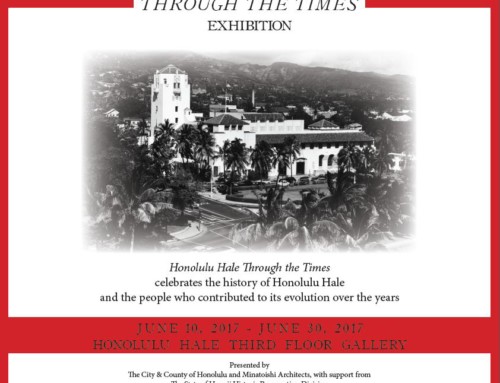

CESAR LAURE / SPECIAL TO THE HONOLULU STAR-ADVERTISER

2 .PU‘UHONUA O HONAUNAU NATIONAL HISTORICAL PARK

It contains a puuhonua, or place of refuge, which served as a sanctuary.

>> Acres: 420

>> Park established: July 1, 1961

Mauna Loa rises in the distance from the puuhonua. Last year, air samples taken at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Mauna Loa Observatory measured carbon dioxide at an average daily level of 400 parts per million — a concentration never before seen by humans.

For nearly 60 years the government-run outpost in Mauna Loa’s remote heights has provided among the best data on the world’s rising greenhouse gas levels.

Tuesday’s UCS report also highlighted various NASA testing and launching coastal sites, a historic California gold rush town, and the Statue of Liberty, which was battered in 2012 by Hurricane Sandy.

For Native Hawaiians, protecting the island’s coastal historic places from rising seas are especially critical, Cachola said. If they’re lost, “there goes not just a place, but a whole spiritual process,” he said.

__

Dire Warning

Thirty significant sites in the United States are listed as needing further protection.

____________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Historic Hawaii Foundation 1974~2014 ~ Celebrating 40 years of preservation in Hawaii!

We’re Social! Like us on Facebook Follow us on Twitter

Sign up for our E-news for the latest on preservation-related events, news and issues here in Hawai‘i & beyond.