91-1235 Alanui Mauka Street/Ewa Sugar Plantation Villages

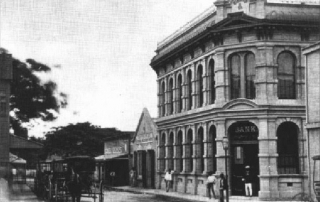

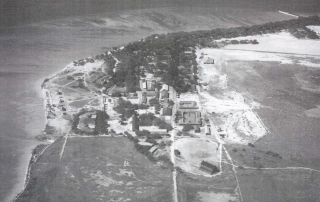

Address 1-1235 Alanui Mauka Street, ‘Ewa Beach HI 96706 TMK (1) 9-1-101:069 SHPD Historic Site Number 80-12-9786 Abstract The historic district of Ewa Sugar Plantation Villages is on the dry southwestern coast of the island of Oahu, known as the Honouliuli plain. It is significant for its association with Ewa Sugar Plantation, which played an influential role in Hawaii's economy, culture, and politics throughout most of the twentieth century. It is also significant as an historic district for its vernacular architecture. The district includes the Verona, Tenney, and Renton Villages, which are 3 of the 8 that formerly provided worker housing for the Ewa Sugar Plantation. The district includes 285 contributing structures, 1 cemetery, and 2 non-contributing buildings. Each of the distinct villages was expressive of different cultures and ethnic groups, had its own architectural and landscaping character with physical separation formerly by cane fields, now open fields. Within the villages, a grid pattern with a hierarchy of streets organizes the layout. Most of the workers’ houses are rectangular, hip-roof, single-wall construction, and sited to create maximum cross-ventilation. The plantation restricted the homes' colors to white, off white, rust, red slate, gray and green. In addition, several of the prominent buildings were designed by master architects, such as Hart Wood's administration building and William Furer's plantation store. This list of Hawaii’s historic properties is provided as a public service by Historic Hawaii Foundation. It is not the official list of properties designated on the Hawaii State Register of Historic Places. For official designations and determinations of eligibility, contact the State Historic Preservation Division of the Department of Land and Natural Resources of the State of Hawaii at [...]