Kaimuki: A Brief History

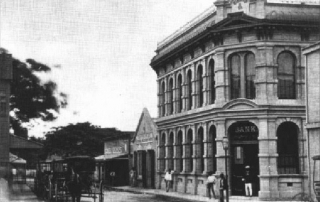

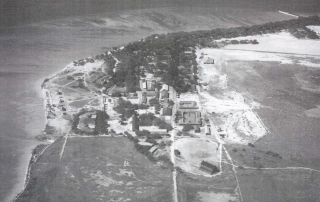

Address Honolulu, HI 96816 Built From 1898 Dry, dusty Kaimuki The observatory was an ideal place to watch Haley's Comet in 1910. Kapahulu Ave. under construction Kaimuki trolley Waialae Avenue storefronts c. 1920 Queen Theater on Waialae Ave. was an anchor in Kaimuki's business district. Kaimuki Fire Station was built in 1924 in a Spanish Mission Style designed by G.R. Miller. The former Lam residence was a landmark for over 100 years before it was demolished and replaced by a two-home compound surrounded by a six-foot wall. Photo by Jill Byus Radke Large duplexes are replacing historic homes, destroying the character of the neighborhood, which diminishes the value of neighboring homes (aka "The Teardown Trend"). Photo by Jill Byus Radke By Jill Byus Radke for Historic Hawaii Foundation Kaimuki is a classic early twentieth century neighborhood on the Koko Head side of downtown Honolulu. Kaimukī means ‘tī oven', a reference to the legend of the Menehune cooking tī roots in the area. Kaimuki is a naturally dusty, dry area that was not heavily populated during precontact times because of a lack of water. The only spring known today is on Luakaha Street near the Salvation Army. There were up to four heiau in the Kaimukī area: Maumae (Sierra Drive) Honolulu side of Kaimuki Hill Between Ocean View Drive and former Waialae Drive-In Parking lot at Lē‘ahi Hospital Early Land Uses When King Kamehemeha stationed his troops on the beaches of Waikīkī in preparation for the battle of O‘ahu, he stationed lookouts at Kaimukī to spot enemies arriving by sea. Pu‘u o [...]