Q: What is recommended for using substitute materials in historic preservation projects?

By Virginia Murison, AIA

Editor’s Note: an abridged version of this Ask an Expert article appeared in the November 2020 issue of Historic Hawai‘i News, Historic Hawai‘i Foundation’s printed newsletter.

The National Historic Preservation Act of 1966 recognized four different treatment categories for a historic property depending upon the property’s significance, existing physical condition, the extent of documentation available and interpretive goals, when applicable: Preservation, Rehabilitation, Restoration and Reconstruction (36 CFR Part 68). For the majority of historic buildings Rehabilitation is the most commonly used treatment (due in part to the Federal Historic Tax Credit program).

Rehabilitation is defined as the act or process of making possible a compatible use for a property through repair, alterations, and additions while preserving those portions or features which convey its historical, cultural, or architectural values.

Adapting a historic structure for a compatible contemporary use involves the preservation of character-defining features, and often repair work and/or selective replacement of severely damaged or missing features. It is in the repair or selective replacement of historic features and materials that the question of “substitute materials” is often considered. The practice of using substitute materials in architecture is not new, yet it continues to pose practical problems and to raise philosophical questions.

Background

The replication (imitation) of historic building materials with a material that is more readily available and/or requires less craftsmanship dates back centuries and includes materials that we consider traditional today. George Washington, for example, used wood painted with sand-impregnated paint at Mount Vernon to imitate cut ashlar stone. This technique along with scoring stucco into block patterns was fairly common in colonial America to imitate stone. (Preservation Brief 16, p1)

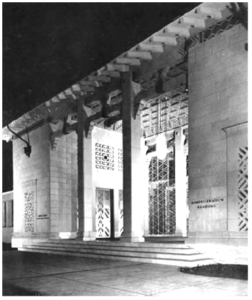

A more recent example is architectural terra cotta, a fired clay product, which was revived in the 19th century in the United States and used widely to replicate the appearance of stonework. This material is used to a high degree of design in Honolulu at both the US Immigration Station (1934) on Ala Moana Boulevard and the Alexander and Baldwin building (1929) on Bishop Street.

Another technique is cast stone made of concrete. The Dillingham Transportation Building (1930) at the Makai end of Bishop Street is an excellent local example of cast stone which was also referred to as “synthetic limestone” at the time. In each of these cases the material is a significant character-defining feature of the original construction.

“In the last few decades, however, and partly as a result of the historic preservation movement, new families of synthetic materials, such as fiberglass, acrylic polymers, and epoxy resins, have been developed and are being used as substitute materials in construction. In some respects, these newer products (often referred to as high tech materials) show great promise; in others, they are less satisfactory, since they are often difficult to integrate physically with the porous historic materials and may be too new to have established solid performance records.” (SOI Guidelines, p. 10)

SOI Standards for Rehabilitation

Standard No. 6: “Deteriorated historic features will be repaired rather than replaced. Where the severity of deterioration requires replacement of a distinctive feature, the new feature will match the old in design, color, texture and, where possible, materials. Replacement of missing features will be substantiated by documentary and physical evidence.” (emphasis added)

Under rehabilitation, repairing often includes the limited replacement “in kind” (i.e. with the same material) or with a compatible substitute material. In this case, we are not dealing with an original construction technique, but with the selective treatment of existing building components (i.e. windows, doors, roofing).

In general, four circumstances warrant the consideration of substitute materials:

- the unavailability of historic materials;

- the unavailability of skilled craftsmen;

- inherent flaws in the original materials; and

- code-required changes.

In addition, if the feature being replaced is relatively inaccessible for routine maintenance, a substitute material requiring less maintenance merits consideration.

Substitute materials must meet four basic criteria before being considered:

- they must be compatible with the historic materials in appearance;

- their physical properties must be similar to those of the historic materials, or be installed in a manner that tolerates differences; and

- they must meet certain basic performance expectations over an extended period of time.

- the closer an element is to the viewer, the more closely the material and craftsmanship must match the original.

Additionally, the closer an element is to the viewer, the more closely the material and craftsmanship must match the original.

Examples of Substitute Materials

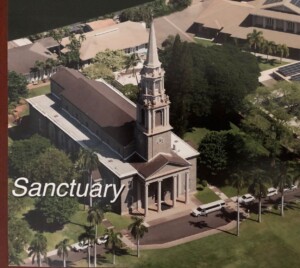

Roofing: In the storms of 2018, the original slate tile roof of Central Union Church was severely damaged which in turn caused water damage to the sanctuary walls. Structural investigation indicated that the weight of the slate was putting undue pressure on the exterior walls. Research located a substitute for the slate tiles consisting of a synthetic composite tile which exactly matched the size, face to weather and profile of the original slate. This compatible substitute, far from view from the street and grounds, was approved by the State Historic Preservation office and assisted with a Freeman Foundation Grant through Historic Hawai‘i Foundation.

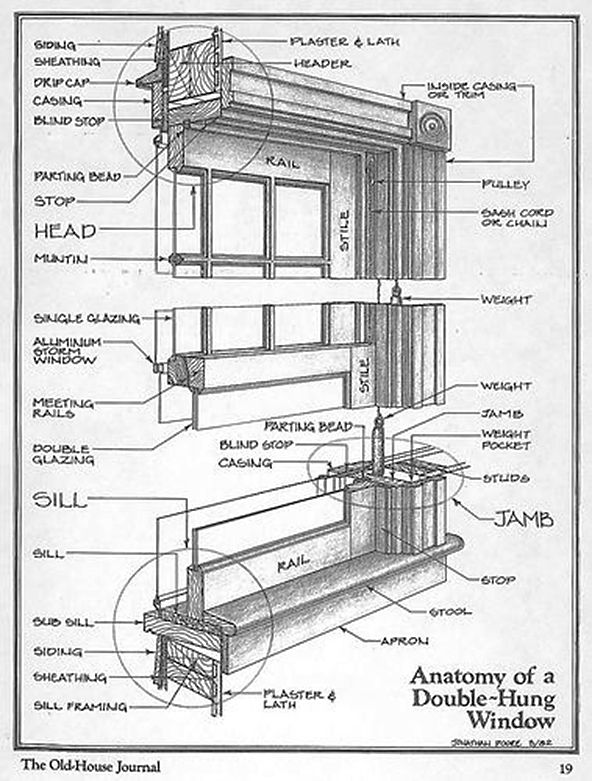

Windows: Frequently a substitute is proposed for replacement of historic wood windows. This poses different considerations as the windows are actively used by the building’s occupants and are viewed from close proximity both inside and from the exterior. Furthermore, the original wood windows are composed of components that can be individually repaired or replaced without replacing the entire window and frame. Also, the way that original windows are integrated into the exterior wall is integral to the weather enclosure of the structure.

Aluminum replacement windows do not duplicate the shape of the original wood frame and sash. Individual muntins (a bar or rigid supporting strip between panes of glass) are simulated with applied strips of metal on either the interior or exterior to simulate divided lights. And finally, vinyl and fiberglass, the most common and least expensive replacements, cannot be repaired but rather the entire window must be replaced when damage or deterioration occurs. The life expectancy of aluminum may be around 40 years and that of vinyl or fiberglass roughly 20-30 years respectively. Compare that to the original windows which still exist in the 3 buildings cited above as well as the Moana Hotel which was built in 1901 (90-115 years).

Aluminum replacement windows do not duplicate the shape of the original wood frame and sash. Individual muntins (a bar or rigid supporting strip between panes of glass) are simulated with applied strips of metal on either the interior or exterior to simulate divided lights. And finally, vinyl and fiberglass, the most common and least expensive replacements, cannot be repaired but rather the entire window must be replaced when damage or deterioration occurs. The life expectancy of aluminum may be around 40 years and that of vinyl or fiberglass roughly 20-30 years respectively. Compare that to the original windows which still exist in the 3 buildings cited above as well as the Moana Hotel which was built in 1901 (90-115 years).

Conclusion

The use of substitute materials should be limited, since replacement of historic materials on a large scale may jeopardize the integrity of a historic resource. Every means of repairing deteriorating historic materials or replacing them with identical materials should be examined before turning to substitute materials.

Because there are so many unknowns regarding the long-term performance of substitute materials, their use should not be considered without a thorough investigation into the proposed materials, the fabricator, the installer, the availability of specifications, and the use of that material in a similar situation in a similar environment.

Sources

- Secretary of the Interior’s Standards for Treatment of Historic Properties with Guidelines for Preserving, Rehabilitating, Restoring and Reconstructing Historic Buildings, National Park Service (updated 2017)

- National Park Service Preservation Brief 16 – The Use of Substitute Materials on Historic Building Exteriors by Sharon C. Park, AIA (1988)

Top photo: the U.S. Immigration Station in Honolulu. Photo credit: Joel Bradshaw, Wikimedia Commons.