Hawaiian Diacritical Marks: What are they and how are they used?

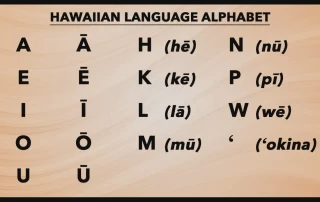

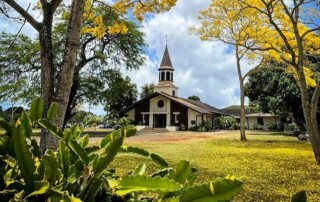

By Lilinoe Andrews Specialist, Chancellor’s Office, University of Hawaiʻi – West Oʻahu Hawaiian diacritical marks comprise just two symbols: the glottal stop (ʻokina) and the macron (kahakō). Are they important? Worth the extra time it takes to insert them into your text? That depends, so let’s discuss. Simply speaking, the two diacritical marks are a way to show how a Hawaiian word should sound to a person unfamiliar with a particular word. More importantly, those two little marks are keeping the Hawaiian language alive. In 1826, a committee of seven missionary gentlemen thought diacriticals were important enough to wrestle mightily with them in the challenge to put the once oral language to print. They decided, after doing similar work in Tahiti, that Hawaiian should have just twelve letters. The ʻokina appeared in Andrews’ dictionary in 1865 and the kahakō in Judd, Pukui, and Stokes’ dictionary and grammar in 1945. In 1978 the ʻAhahui ʻŌlelo Hawaiʻi published “Recommendations and Comments on the Hawaiian Spelling Project” and standardized the use of the ʻokina and kahakō. Not only do the ʻokina and kahakō change the sound of a word, they often end up changing its meaning. For example, these are separate words: pau=completed paʻu=soot paʻū=damp, soaked pāʻū=woman’s skirt Diacriticals are important to keeping Hawaiian (the fastest growing native language in the U.S.) alive because they help expand the lexicon and give the language the subtlety that fluent speakers know by heart. And they are helpful for those unfamiliar with the language, like little cheat marks to keep you from getting your pāʻū all paʻū. Your kumu hula would not be happy. There are a few contexts where diacriticalizing is not seen. For example, in the Niʻihau church [...]