Question: What is the estimate for the number of people supported by and lived/worked in the Kōloa area at its peak?

Dr. Hammatt: The estimated extent of what we know as Kōloa Field System was approximately 2,400 acres extending from Lawa‘i from the west and Weli Weli to the east. Based on this extent and production of the field system there were likely estimated a few thousand during pre-Contact period.

Post-Contact documentation including Judd (1932) states they “observed that the population of Kōloa must have been several thousand before European contact.” It was also stated the population in the early 1840s were “about two thousand people, including many foreigners” (James Jackson Jarves 1844), however, other sources such as a report by missionaries on Kaua‘i, the inhabitants of the ahupua‘a numbered 2,166 (cited in Palama and Stauder 1973:16; also found in the newspaper, Garden Island, 27 July 1935). However, in this census, the designation of Kōloa was used to refer to the whole area between Wahiawa and Kalapakī. An article in the Pacific Commercial Advertiser of December 21, 1867 estimated that the population in 1838 was about 3,000, though by 1867, it had been reduced to a third of that number.

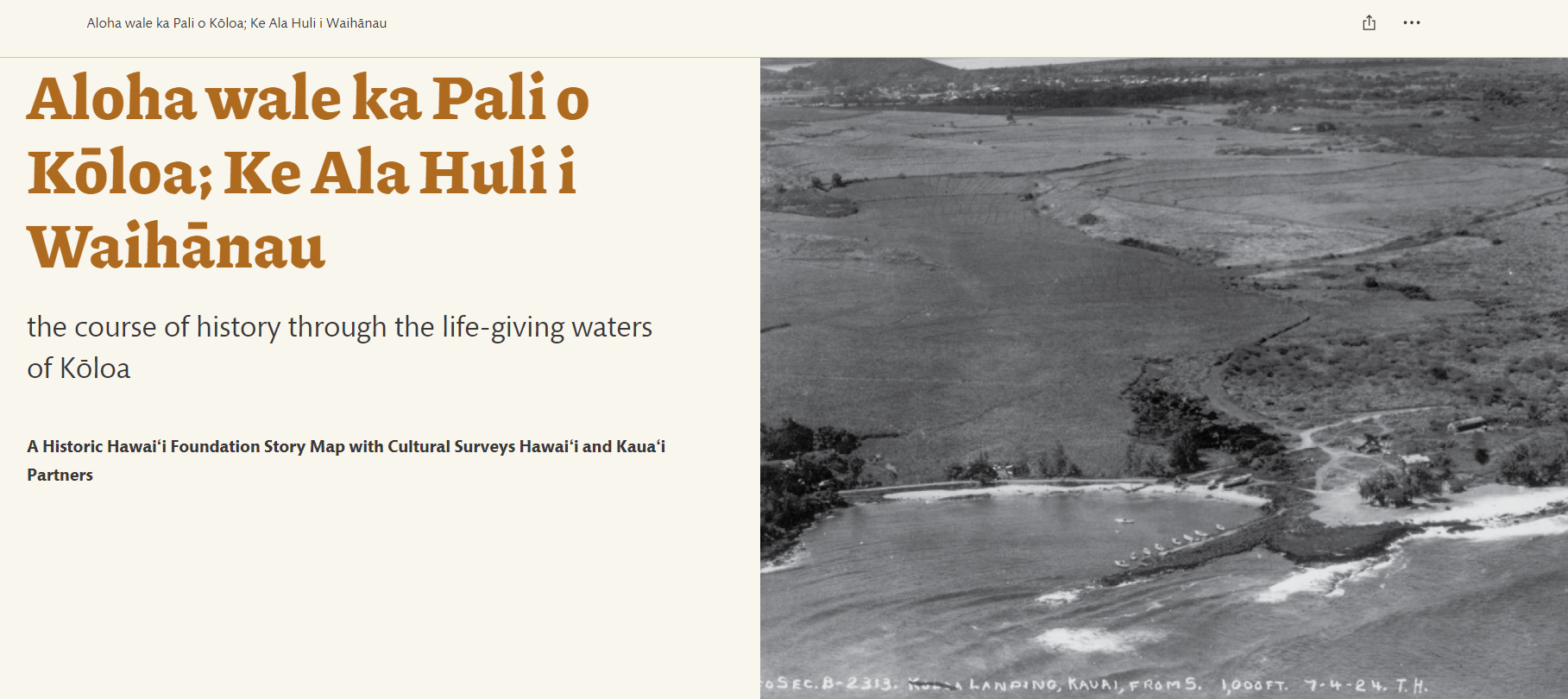

On the other hand, the advent of the Ladd and Company enterprise transformed Kōloa into a commercial center. Activity at Kōloa Landing at this time is described as: “The port of Kōloa did a remarkable amount of trade considering the fact that the roadstead was not safe except when the trade winds blew. Most vessels preferred not to anchor but to lay off during the process of loading, rather than risk the chance of being wrecked by a sudden change of wind. An estimate in 1857 stated that 10,000 barrels of sweet potatoes were grown each year at Kōloa and that the crop furnished nearly all the potatoes sent to California from Hawaii. Sugar and molasses were also chief articles of export” [Judd 1935:325-326]. This suggests the Kōloa Field System was producing more crops than needed to support residents to be able to trade and sell the fruits of their labor.

Question: How can we visit these preserves? Do we just walk on?

Dr. Hammatt: The Kiahuna archaeological preserve area 1 is open to the public and can be accessed on the makai side of the Kiahuna Golf Course parking lot. The preserve area contains a map upon entrance and signage throughout. If/when accessing, take extra care traversing on the rocky terrain and be careful not to move the pōhaku. The other four preserve areas are within private residential areas.

Question: What archaeological data suggests that they are heiau and not a cattle pen?

Dr. Hammatt: A heiau is not an enclosure. The placement of the heiau in the Kiahuna Preserve Area 2 is in a prominent place in a high point commanding views of the surrounding terrain and is massive in structure. There are three depressions on its surface which we interpret as possibly utilized for placement of ki‘i (image, idol, statue)—which is an indicator for places of worship.

Question: Is there a key that corresponds historic maps to current roads?

Dr. Hammatt: The archaeological map drawings of the Kiahuna archaeological preserve areas were digitized and do not contain reference to current roads aside from Hapa Road.

Question: Building this involved planning and design. So this must mean that Hawaiian civilization understood math, physics, engineering and hydraulics. That also means Hawaiian civilization had language to communicate about the above. Please comment Dr. Hammatt.

Dr. Hammatt: In the investigation records of the Kōloa Field System, there is no evidence of a highly stratified society, but rather discerned a social network based on cooperation, sharing of resources, fair allocation of water in close quarters with neighbors. Based on the archaeological record, the Kōloa Field System likely operated as a tightly integrated society with very distinct status and roles and likely had a well-organized social system. The Hawaiians had a great understanding of the behavior of water and hydrology. The Kōloa Field System is a result of a progressive process, which likely started in the mauka portions, expanded makai widening and extending east-west, by following the topography of the existing landscape. The goal of the design was to keep the water as high as possible as this served as the “backbone” of the Kōloa Field System. The placement of fields/lo‘i progressed with the development of the ‘auwai from mauka to makai–feeding water from the higher elevated areas to the non-irrigatable portions of the landscapes. The rocky bluffs were utilized for habitation and dryland crops such as sweet potatoes (‘uala) and banana (mai‘a).

In the concept of architects (kuhikuhipu‘uone), they likely prepared a model for each segment of the Kōloa Field System before they were constructed. The many pōhaku were likely transported to the Kōloa Field System with an assembly line strategy. The Kōloa Field System was originally a rocky landscape with no soil. Once the ‘auwai was constructed, which we believe is the first element constructed, the soil was agitated in the mauka areas and the water that fed into the ‘auwai carried soil to the makai areas. We know this from completing cross-sections of the ‘auwai which show heavy deposits of soil below the ‘auwai in addition and apart from the stone linings. The habitation areas, particularly platforms, were located in high areas on the rocky bluffs and shelters were conveniently located adjacent to the irrigated fields.

Question: Hal mentioned something about the stones being used to discourage mosquitoes. Do we know when/how mosquitos were introduced to the Islands?

Dr. Hammatt: Basalt fireplaces were often found within habitation platforms exclusively in the Kōloa Field System and were likely initially utilized for warmth and later as a mosquito deterrent introduced to Hawai‘i on post-Contact ships in the early 1800s.

Question: Did the sugar developers irrigate from the historic auwais?

Dr. Hammatt: The pre- and early post-Contact Kōloa field system’s water source was Maulili Pond, which is on the makai side of Kōloa town. From there the ‘auwai system bifurcated multiple times as they headed makai all the way to the shoreline covering all the way from the boundary of the Lawa‘i ahupua‘a to the west and to the boundary line of Kōloa and Weliweli to the east.

The sugar developers did not irrigate from the ‘auwai, as far as we know. The Kōloa field system relied on small field that were integrated into the uneven landscape as opposed to the extensive land modification involved in sugarcane cultivation that were accomplished with heavy equipment.

On the question of whether the pre-Contact ‘auwai were used for the cultivation of sugar in post-Contact times, the water source for the sugar was acquired from specifically constructed reservoirs mauka of the sugarcane fields. These reservoirs are still present today, one of which is on the east side of Maluhia Road/tree tunnel.