By Lilinoe Andrews

Specialist, Chancellor’s Office, University of Hawaiʻi – West Oʻahu

Hawaiian diacritical marks comprise just two symbols: the glottal stop (ʻokina) and the macron (kahakō). Are they important? Worth the extra time it takes to insert them into your text? That depends, so let’s discuss.

Simply speaking, the two diacritical marks are a way to show how a Hawaiian word should sound to a person unfamiliar with a particular word.

More importantly, those two little marks are keeping the Hawaiian language alive.

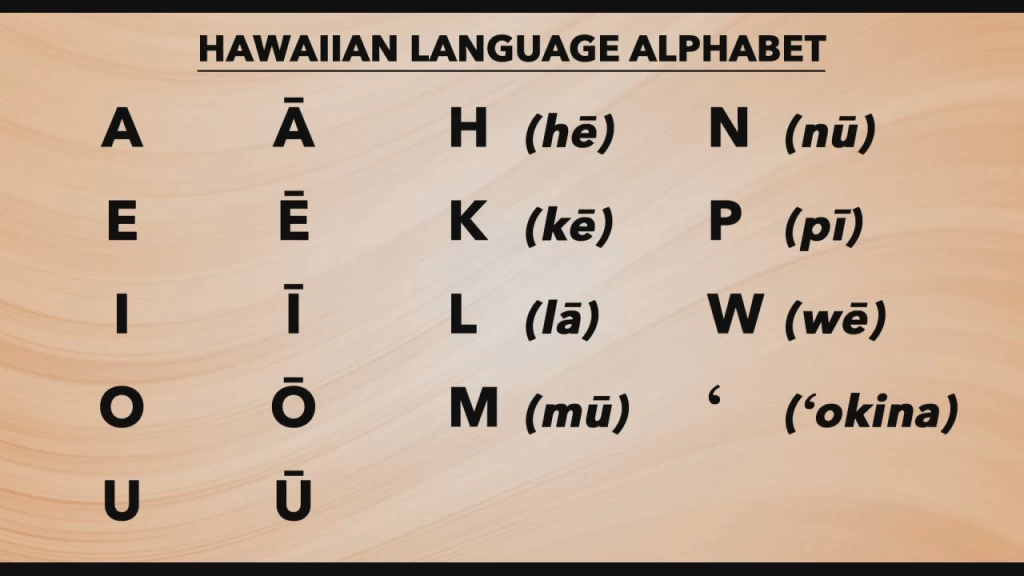

In 1826, a committee of seven missionary gentlemen thought diacriticals were important enough to wrestle mightily with them in the challenge to put the once oral language to print. They decided, after doing similar work in Tahiti, that Hawaiian should have just twelve letters. The ʻokina appeared in Andrews’ dictionary in 1865 and the kahakō in Judd, Pukui, and Stokes’ dictionary and grammar in 1945.

In 1978 the ʻAhahui ʻŌlelo Hawaiʻi published “Recommendations and Comments on the Hawaiian Spelling Project” and standardized the use of the ʻokina and kahakō.

Not only do the ʻokina and kahakō change the sound of a word, they often end up changing its meaning. For example, these are separate words:

pau=completed

paʻu=soot

paʻū=damp, soaked

pāʻū=woman’s skirt

Diacriticals are important to keeping Hawaiian (the fastest growing native language in the U.S.) alive because they help expand the lexicon and give the language the subtlety that fluent speakers know by heart. And they are helpful for those unfamiliar with the language, like little cheat marks to keep you from getting your pāʻū all paʻū. Your kumu hula would not be happy.

There are a few contexts where diacriticalizing is not seen. For example, in the Niʻihau church where the Hawaiian Bible does not include diacriticals, readings are done exactly as they appear, but all other speaking, discussion, and conversation reverts back to the Niʻihau dialect which does include the kahakō and ʻokina. Another example is in proper names: if a family (see one of the dictionary authors above) or a company does not use diacriticals, we shouldn’t add them in. This, and the other conventions mentioned here, apply even when using proper names in completely Hawaiian text.

The ʻokina is not an apostrophe. An apostrophe is shaped like a number nine with a tail that curls left. An ‘okina is like a number six whose top slants to the right. And yes, it is perfectly acceptible to use an ʻokina in close proximity to an apostrophe, as in: Hawaiʻi’s.

Typing Hawaiian is easy thanks to the early efforts of Keola Donaghy with Apple and Microsoft. First, make sure the Hawaiian keyboard is selected on your computer. For the ʻokina: PC and Mac users, simply press the apostrophe key. (For a regular apostrophe: PC users press the right-alt key; for Mac users hold the option key down and press the apostrophe/closed quotes key.)

For the kahakō to display above a vowel: PC users press the right-alt key and type a vowel; Mac users hold the option key down and type a vowel. (For upper case vowels, hold the shift key down along with the keystrokes just listed.)

Most of the fonts we use on both PCs and Macs are of the Unicode variety which means they display the same diacriticals you type no matter what kind of computer they are eventually viewed on or printed from..

RESOURCES

The Hawai‘i Tourism Authority has also developed an AutoCorrect Tool that can be installed for use with Microsoft Word. When Hawaiian words with proper diacritical marks are added to the dictionary, the system will automatically add the ‘okina and kahakō to common Hawaiian words. Download the tool.

Tools for the correct spelling of Hawaiian words abound: wehewehe.com is quick and easy, looking up words across several dictionaries at once. Bookmark or tab it on your computer. A desk reference set should include the Elbert & Pukui dictionary, Pukui’s Place Names of Hawaiʻi, and Pukui’s ʻŌlelo Noʻeau to get more nuance on your word choice and to see how it is actually used in the language.

Editor’s note: This article appeared in the January 2019 issue of Historic Hawaiʻi News.