This article, researched and written by Hawaiian Mission Houses, commemorates the Bicentennial Anniversary of Hawai‘i’s first printing press and the development of a written Hawaiian language.

‘Ōlelo Hawai‘i

For centuries, the Hawaiian language thrived in a strong oral tradition, using chant and song to record history and genealogies and share stories over generations. Recording the language in written symbols was an unfamiliar concept. ‘Ōpūkahai‘a, a native Hawaiian man who made his way to Connecticut and converted to Christianity there, began developing a system of writing the Hawaiian language that incorporated both number and letters. He died in 1818 before returning to Hawai‘i, and his system was unused.

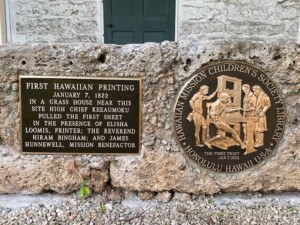

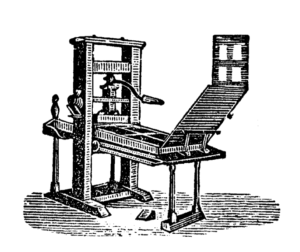

The Pioneer company brought the original Ramage printing press to Hawaiʻi in 1820. It was used to print the first written Hawaiian language documents. A replica today is in the Hawaiian Mission Houses Hale Paʻi. Image courtesy Hawaiian Mission Houses.

The missionaries of the Pioneer Company, who were inspired by ‘Ōpūkahai‘a’s life story, believed that the Bible and the ability to read it was fundamental to becoming a Christian. They were committed that the Bible be in the Hawaiian language, which meant developing the written word. The ali‘i drove this effort, with King Kamehameha II asking the missionaries to teach his people to read and write in ‘ōlelo Hawai‘i, and Queen Ka‘ahumanu later stating, “When schools are established, all the people shall learn the palapala (writing).”[1]

Work done from 1820-22 to establish a Hawaiian alphabet is not well documented, but the first printing revealed an alphabet of five vowels and twelve consonants. The codification and standardization of the written Hawaiian language took shape between 1822-26, and was a collaborative effort involving Hawaiian scholars, Tahitian missionaries, ABCFM missionaries, and others. The final alphabet included a total of twelve letters, reducing the number of consonants to seven along with five vowels.

The First Print

The Pioneer Company of missionaries, including a printer, Elisha Loomis, brought with them a Ramage printing press aboard the Thaddeus in 1820. Set up in a thatched house, it was not used until they were ready to print the first Hawaiian primer, or spelling book.

On January 7, 1822, Loomis set the type and inked the press, then asked Ke‘eaumoku, the governor of Maui, to perform the first “pull.” The second sheet was pulled by Loomis, and the third by James Hunnewell, first officer on the Thaddeus and whose name is identified in many ways with 19th century Hawaiian history.

Page 1 of the first book printed in January 1822; courtesy Hawaiian Mission Houses.

The printed page was a broadside of what would become the second and third pages of the eight-page primer. Eight additional pages were added to the primer by February, 1822, with 500 copies made then and an additional 2,000 copies by September.

A Legacy of Literacy

With the ability now to mass produce a written primer, the Hawaiian Kingdom had an unprecedented and amazing rise in literacy. In 1853 an estimated 75% of all people in the Kingdom over the age of 16 were literate, and by 1878, 80% of them were literate in Hawaiian, English, or a European language, making Hawai‘i one of the most literate nations in the world at the time.[2]

Native Hawaiians wrote and published their own works of history and culture, including newspapers, periodicals, letters, journals, and academic works, creating one of the largest indigenous-produced, native-language bodies of written literature.

A Historical Timeline of the First Printing

A Historical Timeline of the First Printing

- April 14, 1820: The Thaddeus, carrying the Pioneer Company and the Ramage printing press, anchored in Honolulu Harbor.

» Elisha Loomis, member of the Pioneer Company, was a printer by trade. His wife, Maria, became a bookbinder.

» Kānaka maoli worked with missionaries to develop the first orthography for ‘ōlelo Hawai‘i.

- January 7, 1822: the first prints of a primer for ‘ōlelo Hawai‘i were pulled on the press.

» Ke‘eaumoku, governor of Maui, pulled the first sheet. Loomis struck the second, and James Hunnewell, first officer of the Thaddeus and Mission benefactor, pulled the third.

- Commemorative plaques installed in front of the print shop

- Photos courtesy of Hawaiian Mission Houses

“Here is my word to you…There are many people, but few letters. I want you to send eight hundred Hawaiian letters. We want literacy, it may make us wise.”

– Ka‘ahumanu letter to Kamamalu, July 1822

Hawaiian Mission Houses cares for thousands of these pieces and many other writings from the mid-1800s. Members of the general public are welcome to visit its Archives either in person or via its website at https://www.missionhouses.org.

[1] Charles S. Stewart, Journal of Residence in the Sandwich Islands in the years 1823, 1824, and 1825. London, H. Fisher and Son and Jackson, 1828. Pg. 321.

[2] Demographic Statistics of Hawai‘i 1778-1965. Robert C. Schmitt. Pg. 12. University of Hawai‘i Press, Honolulu. 1968.

This article is republished with permission from Hawaiian Mission Houses. The opinions or views expressed in this article are those of Hawaiian Mission Houses and do not purport to reflect the opinions or views of Historic Hawai‘i Foundation or its members.