Note from Historic Hawai‘i Foundation: Heather Leilani Kekahuna moved to Hawai‘i in 2018 to continue her studies and explore her ancestral roots. She came to volunteer with HHF through Poʻi Nā Nalu, Honolulu Community College’s oldest Native Hawaiian-serving program. When we were looking for a student volunteer to serve as a docent at our Dillingham Ranch Historic Open House event in May of 2019, we were hoping to find someone interested to research and share Hawaiian history and mo‘olelo of the site. Heather answered the call.

“Maika‘i ka hana o ka lima, ‘ono no ka a‘i a kawaha!

When the hands do good work, the mouth eats good food!

(ʻŌlelo aʻo mai kupuna Daniel Kaōpūiki Sr.)

My name is Heather Leilani Kekahuna. I was born in Southern California and returned to school in 2016 at the College of the Desert in Palm Desert to pursue my passion for history. After being introduced to anthropology, I changed my major to anthropology with a minor in history. I moved to Hawai‘i in 2018 to further my education in the place where my kūpuna lived.

I’ve always felt disconnected from my identity and wanted to learn more about where my kūpuna came from. Attending Honolulu Community College through the Hulilikekukui Native Hawaiian Center I had the opportunity to participate in a summer internship program in Ke’ei and Honaunau on Hawai‘i Island where I completed the WAHI Kūpuna Internship Program in 2018. In the spring of 2019 I researched the Waialua Ahupua‘a and told mo‘olelo as a volunteer docent at Historic Hawai‘i Foundation’s Dillingham Ranch Historic Home Open House event. After graduating from HCC with an associate’s degree, I transferred to the University of Hawai‘i at Hilo where I am president of the Anthropology Club, Ku‘ikapiko. My hope is to work in a museum one day and teach secondary education in World History.

I’ve always felt disconnected from my identity and wanted to learn more about where my kūpuna came from. Attending Honolulu Community College through the Hulilikekukui Native Hawaiian Center I had the opportunity to participate in a summer internship program in Ke’ei and Honaunau on Hawai‘i Island where I completed the WAHI Kūpuna Internship Program in 2018. In the spring of 2019 I researched the Waialua Ahupua‘a and told mo‘olelo as a volunteer docent at Historic Hawai‘i Foundation’s Dillingham Ranch Historic Home Open House event. After graduating from HCC with an associate’s degree, I transferred to the University of Hawai‘i at Hilo where I am president of the Anthropology Club, Ku‘ikapiko. My hope is to work in a museum one day and teach secondary education in World History.

When I first stepped foot on the island of Hawai‘i, my intention was to learn about Cultural Resource Management, retracing the very steps of my kūpuna, Henry E.P. Kekahuna by mapping and preserving ancestral knowledge for future generations. But through my internship in 2018, I realized there was a little bit more than just archaeology and history I was impassioned about. There was a realization of this sense of belonging and rich genealogical connection I have to this sacred ‘āina.

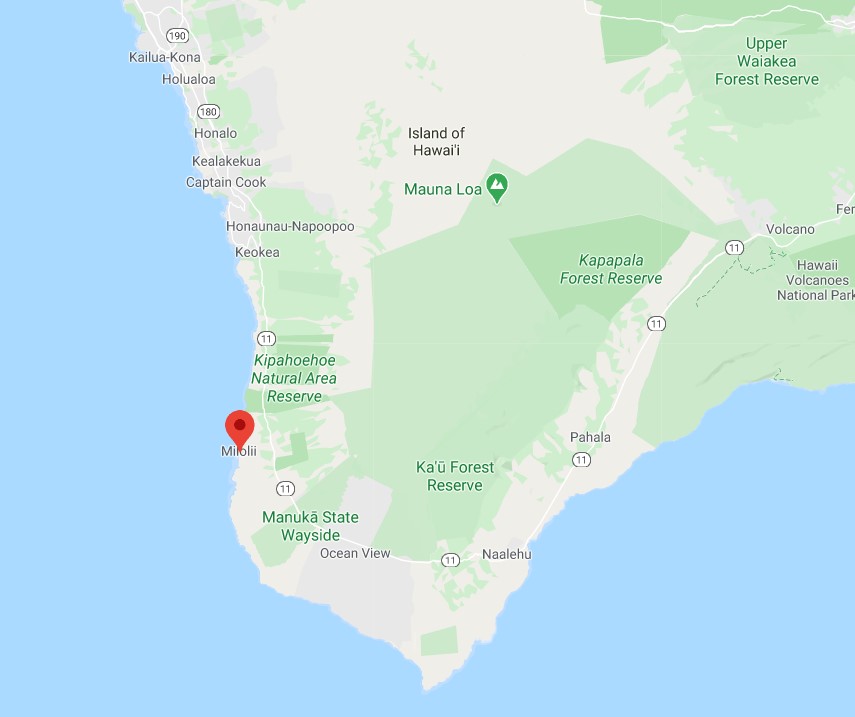

While on my return from Hawai‘i Island to O’ahu, I looked down from my window during takeoff and I thought to myself, this is exactly why I moved to Hawai‘i from California in the first place, to learn and understand the meaning of who I am, my identity, culture and the ways of my ancestors. This is something tangible I can connect to. I also understood that there is a deeper meaning behind why I must first understand who I am and where I come from before I can move forward with my studies and career so I can stay grounded in my identity throughout my college life and achieve what I am striving for. This epiphany of sorts led me to return to Hawai‘i Island and enroll at the University of Hawai‘i at Hilo. It was a step toward understanding the place my ancestors called home and why this was home. The more I learned, the more I began to understand what I wanted to learn about and how to do that. My exploration led me to ask questions about my ancestral connections to Hawai‘i. That’s when I came across my familial connection to, Miloli‘i, the last fishing village on the Island of Hawai’i.

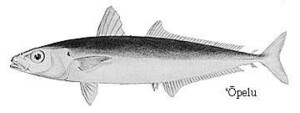

Miloli‘i is in the Ahupua‘a of Miloli‘i, District of South Kona on the Island of Hawai’i and an established coastal village settlement dating back to early Polynesians. It is the most traditional and last fishing village in Hawaiʻi nei. Miloli’i is famous for its ‘Ōpelu fishing. For many years Miloli‘i ‘ohana spent their lives catering to ‘Ōpelu fishing.

Miloli‘i is in the Ahupua‘a of Miloli‘i, District of South Kona on the Island of Hawai’i and an established coastal village settlement dating back to early Polynesians. It is the most traditional and last fishing village in Hawaiʻi nei. Miloli’i is famous for its ‘Ōpelu fishing. For many years Miloli‘i ‘ohana spent their lives catering to ‘Ōpelu fishing.

“Keiki would go to school at the schoolhouse and after school they would go with their parents to catch ‘Ōpelu.” Sarah (Kapela) Kaupiko, Miloli‘i.

Ōpelu fishing was the practice of the families who lived in this region from Miloli‘i to Kapu‘a, and the neighboring lands. ‘Ōpelu helped build local relationships.

I learned I have genealogical ties to Miloli‘i going back to my great grandmother, Tūtū Kilikina “Christine” Paulo Lohelohe Kekahuna- Hookano (1900-1960). Kilikina was the daughter of Ana Kaikuahine Kua and Paulo Kalama Lohelohe—both of whom were from Miloli‘i. Before the lava flow of 1919, Kilikina moved to Oahu and met my great grandfather Daniel I‘oane Kekahuna while he was in the military. She stayed with him for a little while on Oahu then they married and moved to the west of Maui. There she gave birth to her son, Paulo Kalama Kekahuna, my grandfather. After Kilikina’s husband passed away in Olowalu Maui, she moved to O‘ahu to live with my grandfather’s brother in Papakolea. There she met her second husband Ho‘okano.

Tūtū Kilikina never returned to Miloli‘i. She passed away in 1960 when my grandfather (Paulo) was away at war in Vietnam. My grandfather would visit Miloli‘i from time to time to be with ‘ohana. During his visits Paulo would gather mo‘olelo of his mother and spend time with cousins and uncles.

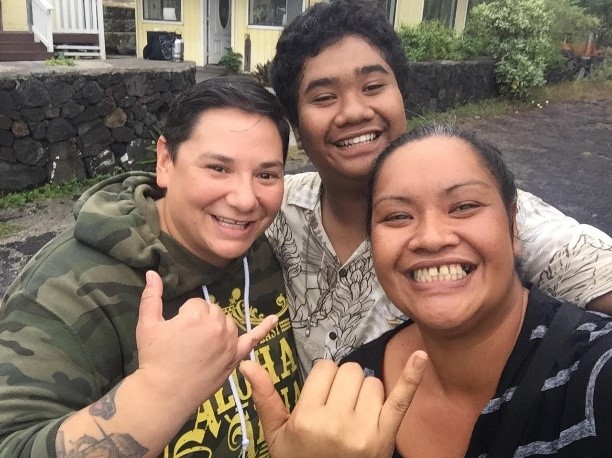

My grandfather Paulo passed in 1995 and 25 years later I found myself in Miloli‘i meeting my extended ‘ohana for the first time. I visited Miloli‘i often and attended Hau‘oli Kamana‘o Church where my tutu Kilikina was baptized and attended services every Sunday. I attended family gatherings, holiday celebrations and learned about the ahupua‘a of Miloli‘i, fishing practices and my genealogy. My grandfather Paulo and great grandmother Tūtū Kilikina would be very proud.

Hau’oli Kamana’o (happy is the thought) Church in Miloliʻi. In 1868, a tsunami triggered by an earthquake in Chile moved the Hau‘oli Kamaha‘o Church about 300 yards inland with little or no damage. The original location of the church is now underwater. There was no loss of life and missing children were led to safety in caves and rescued 5 days later. (Huapala)

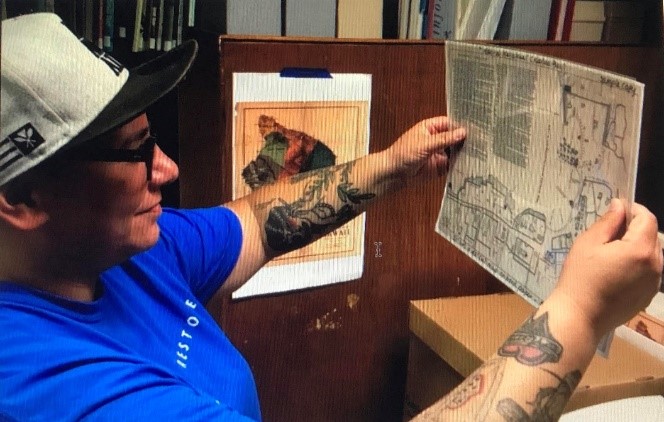

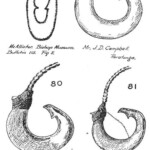

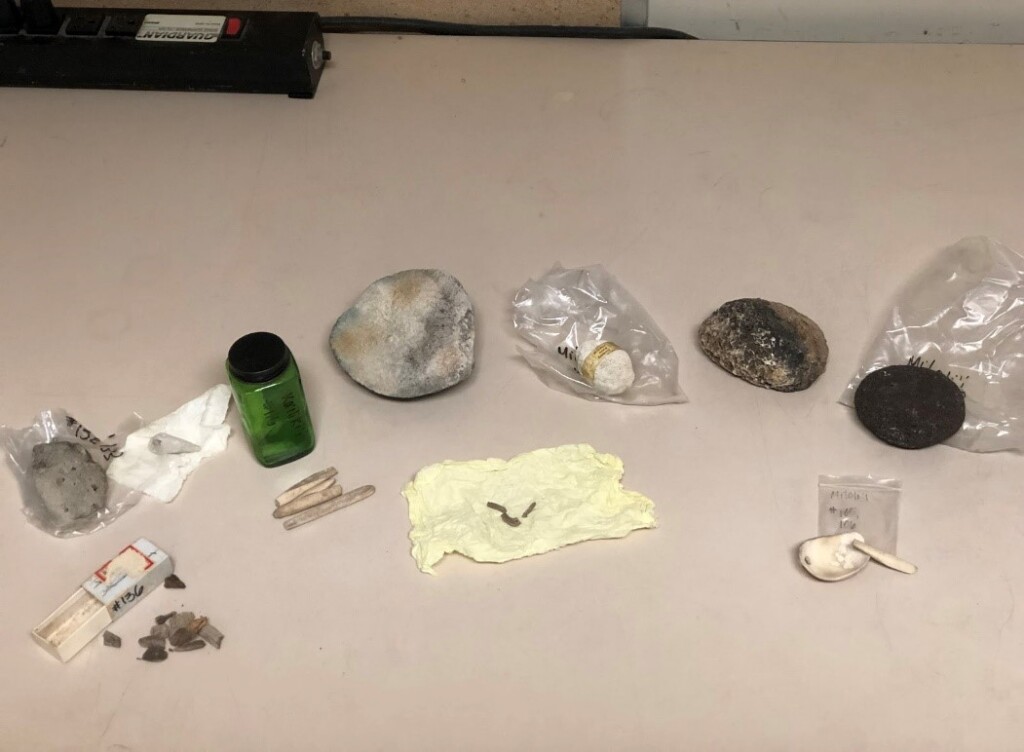

The discovery of my lineage and connection to Miloli‘i informed the project I chose for my Museology 470 class at UH Hilo this past semester. Through serendipity, I found a box in the Anthropology Department Collections Room in a far back corner of a cabinet. The box was labelled Miloli‘i. It was a surprise to me because that was the only box with artifacts that UH Hilo had of Miloli‘i. It was as if it was calling to me! When I opened the box, I found fishing tools in fairly good condition. I wrote up a condition report and started my research. It was wonderful because prior to this finding, I was intent on building my connections with Miloli‘i and the community I come from. I was getting to know the place my Tūtū Kilikina was from and it became of personal importance to take on this project.

Fishing tools from Miloli’i, part of the University of Hawai’i at Hilo Anthropology Department collections room. Artifacts are in good-fair condition. Broken in 3 pieces is a fish hook, a modified stone coral, modified pohaku, sea shell, possible wood, animal bones and fossilized sea urchin.

I began researching the ancestral knowledge of Miloli‘i related to ‘Ōpelu fishing.

“Too many fish but no money. We would dry the fish and exchange in Honolulu. We didn’t take money”– Sarah (Kapela) Kaupiko, Miloli’i

My research led me to Miloli‘i fishing mo‘olelo and I found this this description of the village from the early 1900s:

“This region is seldom visited. Its chief points of interest are the remains of a heiau, mauka of the Catholic church at Miloli‘i, some fine papa konane at the south end of the same village, a well preserved kuula where fishermen offer offerings of fruit to insure a good catch, by the beach south of Miloli‘i, where the Honomalino Ranch fence crosses the trail; while all along the trail are smaller kuulas, and at many points the foundations of villages, where old implements may still be found.” (Maly and Maly, 2003).

I discovered that fishing mo‘olelo are told all over Oceania by Pacific Islander cultures and that there are different versions of these stories shared in different places and many are very famous. One well known mo’olelo is told below.

In Hawaii there is a mo‘olelo about the star line Scorpius as being the demigod Maui’s Fishhook. According to the Hawaiian Astronomical Society, one day Maui went fishing with his brothers in their outrigger canoe. He brought with him a magic fishhook, instructing his brothers that whatever he caught with it, they were to continue paddling and never look back. Maui caught a huge object and asked his brothers to paddle harder while he pulled the line. As Maui hauled, many rocks appeared. The more he pulled, the more rocks appeared. Finally, he pulled hard enough that the large chunks of land surfaced from the ocean. His brothers, tired from all the rowing, and curious about Maui’s catch, looked back. One of the brothers called out, “Look, Maui is pulling up land!” Furious, Maui responded, “Fools! Had you not looked back; these islands would have been a great land.” We now know these islands as Hawai‘i. In Aotearoa they tell a similar story about Maui and their land.

There are other legends describing the use of human bone used to make fishhooks. A mo‘olelo related to the origin of the names of two villages in the Kapalilua region speaks to this. The mo‘olelo shares that a number of years ago while out fishing, some fishermen of the first village consulted about how they might take two helpless old men who lived along the same land inland from the shore and make fish hooks of their bones! Thence the village was called ‘Ōlelo moana or “word of the ocean.” However, the two old men learned beforehand of the designs of their neighbors and left their dwelling. Not being able to walk due to their age, they crawled to the next houses in the nearby area. That village is presently known as “Kolo” meaning to “crawl”.

In October 1836, missionary Cochran Forbes traveled by canoe from Keālia along the coast of Kapalilua to Kapuʻa. He then traveled north by foot and canoe along the coast to various villages back towards Keālia. His letter, describing the journey provides readers with descriptions of the region, and nature of the scattered settlements along the coast as well as the use of bones to make fishhooks.

“It was the custom to make fishhooks of human bones in old times, especially of the bones of those offered in sacrifice, whose flesh was also taken for bait! …We next came to Kaohe a small village as inaccessible as Opihali…” [Forbes October 1836, in the collection of Hawaiian Mission Children’s Library].

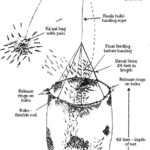

Hawaiians used many fishing methods and even used plants to poison the fish. Many Hawaiians used spears to fish in the coastal shallows along rocky ledges, or even in underwater sea to catch rockfish. Bait that was used just like today depending on the type of fish; woven traps woven like baskets to catch smaller fish and shrimp, nets, Koki`o dye, a noose used for Shark hunting.

Hawaiians made Fishhook cordage from strips of bark from the olonā plant because it is resistant to water and doesn’t stretch and used for fishing in shallow waters.

I also discovered there is a famed mele of Miloli‘i written after the tsunami in 1868 that is still being sung today. It was also sung in the village by a kūpuna, Diane Aki and the famous singer Israel Kamakawiwo‘ole.

La `Elima (Na Elizabeth Kuahaia) La `elima o Pepeluali Waimaka helele(he`e nei)`i ke alanui Paiki pu`olo pa`a i ka lima (Maika pu olo a`a ika lima) Waimaka helele `i i ke alanui! (Ae maka hele he`e nui ike alanui Penei pepe `alala nei (He nei pepe ala`a nei) He hu`i ma`e`ele kou nui kino (E`u ima e hele kou lui kino) Ha`ina `ia mai ana ka puana He mele he inoa no Miloli`i (E mele he noe no Miloli`i)

Today, there are many conservation efforts led by the village.

ʻŌpelu Fisherman / Ocean and Marine Conservationist Uncle Willy Kaupiko is from Miloliʻi and a Vietnam war veteran. Uncle Willy is a advocate for the protection of the precious resources of Miloliʻi, especially the ocean.

Kaimi Namaielua Kaupiko is a native son of the Last Hawaiian Fishing Village of Miloliʻi. He has been working with youth educational programs for the past 15 years in Miloliʻi.

You can learn more about some of the conservation efforts:

The Malolo Project http://paaponomilolii.org

Miloliʻi ʻŌpelu Project https://www.kalanihale.com

“Until today we use the word holoholo. Holoholo means fishing we never speak the word. It’s holoholo.” Hinano Rodrigues (Cousin)

References

(2020). Retrieved 25 April 2020, from https://www.kalanihale.com/

Bishop Museum – Ethnobotany Database. (2020). Retrieved 26 April 2020, from http://data.bishopmuseum.org/ethnobotanydb/ethnobotany.php?b=d&ID=kauila_A

Fishing with Traditional Plant Poisons. (2020). Retrieved 26 April 2020, from https://www.primitiveways.com/fish_toxins.html

Fornander, Abraham. Fornander collection of Hawaiian antiquities and folk-lore. Bishop Museum Press. 1918

Hawaiian Astronomical Society – Scorpius. (2020). Retrieved 25 April 2020, from http://www.hawastsoc.org/deepsky/sco/

Hawaiian Fishing – Haleakalā National Park (U.S. National Park Service). (2020). Retrieved 24 April 2020, from https://www.nps.gov/hale/learn/historyculture/hawaiian-fishing.htm

Hawaiian Lure. (2020). Retrieved 24 April 2020, from https://ocean.si.edu/human-connections/hawaiian-lure

Hawaiian Star Lines. (2020). Retrieved 25 April 2020, from http://archive.hokulea.com/ike/hookele/hawaiian_star_lines.html Home. (2020). Retrieved 25 April 2020, from http://paaponomilolii.org/

Makuakane. Miloliʻi aku nei aʻu la / I ke kau ʻēkake (or, kēkake) la (mele). Kimo Alama Keaulana Collection. Bishop Museum Archives. Date Unknown.

Project Aloha ‘Āina – Ahupuaʻa. (2020). Retrieved 26 April 2020, from http://ulukau.org/gsdl2.81/cgi-bin/cbalohaaina4?a=d&d=D0.9.2>=2&e=010off–00-1–0–010—4——-0-1l–11haw—–00-3-1-000–0-0-11000

ResearchGate | Find and share research. (2020). Retrieved 25 April 2020, from https://www.researchgate.net/

Ulukau: A collection of historical accounts and oral history interviews with elder kamaʻāina fisher-people from the Kapalilua region of South Kona, island of Hawaiʻi (He wahi moʻolelo no na lawaiʻa ma Kapalilua, Kona Hema, Hawaiʻi). (2020). Retrieved 25 April 2020, from http://www.ulukau.org/elib/cgi-bin/library?e=d-0maly5-000Sec–11en-50-20-frameset-book–1-010escapewin&a=d&d=D0&toc=0