By Mindy Pennybacker

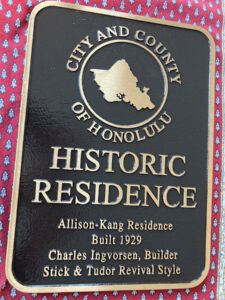

It began with plaque envy. In 2015, after my husband, Don Wallace, and I had purchased 3052 Hibiscus Drive from my four brothers, we noticed that more than a dozen homes in our neighborhood boasted elegant, bronze plaques identifying them as City and County Historic Residences. We wanted a plaque of our own for three reasons.

We wanted to commemorate my late grandparents, Lawrence and Mary Kang, who had bought the house in 1951, and my mother, Dolly Kang Lott, who maintained it with care and resided in it until she died. At times, it had housed up to nine family members from four generations. It is filled with memories of loved ones and big parties, and Don still cooks Korean barbecue on the cinderblock grill my grandfather built.

Don and I had a big mortgage and small salaries, and the city’s property tax exemption for historically designated homes would help us afford to keep the house in the family.

My family has always been proud of the tall, three-story, white wooden house with its peaked, gable roofs and big, double-hung windows admitting air and light from all directions. Don and I thought its age and unique style deserved recognition. It was built in 1929, and the architect was Swedish, my grandfather had said, although he couldn’t recollect the name.

Neighbors said they’d hired architectural specialists who did all the research and filled out the historical designation nomination forms submitted to the Hawai‘i State Historic Preservation Division, known as SHPD. But we heard they charged thousands of dollars. Impecunious and underpaid journalists who prided ourselves on our research skills, we decided to do it ourselves.

We quickly realized we would need lots of help.

Our primary resource was Historic Hawai‘i Foundation. I read dozens of profiles of historic residences on HHF’s website, as well as their guidelines to nomination based on the criterion of architectural significance. We also participated in an HHF online seminar that included homeowners who’d had their houses listed on the historic register and preservation professionals who helped research and write nominations.

We realized our house might meet the criterion of having been owned and inhabited by people who played significant roles in the Honolulu community. My grandparents, the Hawai‘i-born children of Asian immigrants, left the sugar and pineapple plantations where their parents had worked, and started their own business in town. They owned and operated Halm’s Enterprises for 30 years, producing what became Hawai‘i’s best-selling kim chee. The first non-Caucasians to buy a house on Upper Diamond Head Terrace, they worked with their neighbors and The Outdoor Circle to protest a city zoning change that allowed the construction of high-rise apartment buildings along the shoreline of Lower Diamond Head Terrace, on grounds the tall buildings blocked public views of Diamond Head, a historic and culturally significant landmark. The zoning was changed back to single-family. Along the way, the alliance also won the first environmental conservation case in the Hawai‘i courts.

I submitted newspaper articles about Honolulu’s Korean Golf Club, co-founded by my grandfather, and a column by Bob Krauss calling him “the Kim Chee King.”

In 2019, a new plaque appeared on the white picket fence of a wooden cottage on Hibiscus Drive owned by Russell and Ellen Freeman. Ellen, whom I’d known since childhood, had been raised in the house. Russell had done their submission and insisted we could, too. He shared his research with us. He added that, contrary to popular assumption, you didn’t have to prove that your house was designed by a specific architect in order to meet the criterion of architectural significance. He had only been able to identify the builder of his house. “You have to go down to the state tax office and the Bureau of Conveyances to trace your chain of title back in the deed book,” Russell said. “You don’t mind a little dust, do you?”

I took my asthma inhaler and drove downtown, armed with our Tax Map Key number (listed on real property tax assessments) and a diagram of our block with the coordinates for lot, provided by the title company when we applied for our mortgage. Leafing through heavy, dusty black ledgers, I searched backwards in time through title records and building permits.

It was a thrill to find a February, 1872 document written entirely in Hawaiian, in which King Lot, Kamehameha V, granted a tract of royal lands in Waikīkī to Iona Pehu of Palolo. In 1885, the parcel was granted to James Campbell, and in 1921, it was developed by the Waterhouse Co. and became Diamond Head Terrace. In 1924, our lot was purchased by Charles Ingvorsen, a Danish immigrant who built our house in 1929– not Swedish, as my grandfather had thought, but pretty close.

Another thrill was finding the name of the man who’d sold the house to my grandparents in 1951. He was Dr. Samuel Allison, who’d moved to Honolulu in 1942 to serve as director of the bureau of venereal diseases in the Hawai‘i Department of Health during World War II.

If, like me, you’re challenged by spread sheets and filling out and uploading USGS maps and photographs to formatted, 65-page online forms (no, attachments will not be accepted), know that the sooner you accept and embrace the mind-numbing task, the less pain and frustration you will feel. Be patient when, thinking you are following the guidelines, you go to a government office and are told you are at the wrong place, or when the guidelines say photographs should be color, but you later have to go back in and change your 35 photos to black & white.

Make sure from the start, through checking with SHPD by phone or email (the staff promptly responds to both), that you are working with the most current set of guidelines and filling out the most current nomination form. At one point, when I couldn’t find the nomination submittal rules and deadlines for 2023, which hadn’t yet been posted on the SHPD website, Andrea Nandoskar of HHF reached out on my behalf and got the updated calendar.

We couldn’t have done this without the patience, good humor and support of SHPD architectural historian Mary Kodama and secretary Chandra Hirotsu, and the edits to my first draft made by division administrator Alan Downer.

I’m also grateful to architect Tonia Moy, who specializes in historic renovations, for reviewing my first submission and offering one major edit. Our house was not Colonial Revival in style, as I’d thought, but Tudor Revival, even though its façades were plain wood, without stucco coating. “It’s the visible half-beam patterning,” she said. I wanted to pay her for her time but she refused, saying I’d done 99% of the work. Tonia’s determination led to Don’s “aha” moment: our house, he said, was a rare example of Stick style, a short-lived, American adaptation of Tudor Revival.

On March 24, 2023, Don and I drove to Kapolei for the final step: giving a presentation about our house before the Hawai‘i Historic Places Review Board.

Don wore a blue aloha shirt printed with sea horses, and I wore a long orange muumuu in a bird-of-paradise print; both garments had been purchased by my grandmother in 1950 at Liberty House Waikīkī We hoped appearing in period costume would help bring our house’s history to life, but we arrived an hour late, after having gotten lost as thoroughly as if we were time travelers from before the 1977 development of Kapolei.

However, we were greeted with smiles by Dr. Downer, his staff, five members of the Historic Review Board, and the other applicants. I had emailed photos of historic homes in our neighborhood with comparable architectural styles and details to Mary Kodama, who projected them on a screen.

“This is the house that V.D. built,” Don said by way of introduction.

“Not literally,” said Review Board member William Chapman, Interim Dean, University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa, School of Architecture, and everyone laughed. Dr. Chapman then said he was delighted to find another rare example of predominantly Stick architecture in Honolulu.

Another board member, leafing through the nomination document, asked, “Who drew this sketch map?” Embarrassed, I admitted it was me. I’d tried my best to meet the requirement of a 360-degree, crow’s nest view of the house, showing its four facings with numbers correspondences to the photographs. But it looked like a crazy quilt. To my surprise, he praised it as one of the most effective and original models he’d seen.

The next surprise: the board voted on the spot to accept our nomination, and ordered that our house immediately be placed on the register of historic places. Our tax exemption will take effect in fiscal year 2024, but most valuable, to Don and me, is the deep appreciation for neighborliness and community we gained.

Mindy Pennybacker is author of “Surfing Sisterhood Hawai‘i”. Her stories have appeared in The Atlantic, The Honolulu Star-Advertiser, The New York Times, and elsewhere. Besides their home at Diamond Head, she and her husband, Don Wallace, are struggling to preserve a historic, 1830 stone cottage in Brittany, as chronicled in his book, “The French House”.