Hawai‘i Capital Historic District and the History of Postwar American Government Centers

by

Daniel M. Abramson

Professor of Architectural History and Director of Architectural Studies,

Department of History of Art & Architecture, Boston University

I am an architectural history professor at Boston University currently researching a book focused upon postwar American government complexes, including the Hawai‘i State Capitol and nearby 1960s and 1970s municipal, federal, and state buildings in the Civic Center’s landscaped setting.

In 2023, when I contacted the Hawai‘i State Archives, I was fortunate that an archivist, Carol Kellett, drew my attention to the 2019 symposium, “Democracy by Design, The Hawai‘i State Capitol at 50,” organized by a governor- and legislature-appointed task force that included the Historic Hawaii Foundation (HHF), Hawai‘i State Archives, State Foundation on Culture and the Arts, DAGS, local architects and planners, legislators and then-First Lady, Dawn Amano-Ige. The recorded presentations are available on the HHF website and YouTube.

Prior to my recent visit to the Hawai’i State Archives, I was thus able to learn from the symposium’s impressive speakers and their presentations. The talks, especially by Don Hibbard, Bettina Mehnert, David Miller, Katie Stephens, and Kelema Moses, feature invaluable information, primary sources, and extensive images about the history of the State Capitol and Civic Center planning dating back to the 1930s; the evolution of the Capitol Building design; and the cast of significant politicians, businessmen, citizens, and architects involved in the process.

The Historic Hawaii Foundation’s online Capital Historic District story map is also a fantastic resource, as is the booklet by Don Hibbard, Democracy By Design: The Planning and Development of the Hawaii State Capitol, which makes accessible much of the Symposium’s content. I was thus well prepared for the week I spent in April 2024 at the Hawai‘i State Archives, the Hawai‘i State Library, and the University of Hawai’i at Mānoa Library, and visiting the buildings and sites themselves. Governors’ and Comptrollers’ records in the Archives, plus rare, published reports in the Libraries proved particularly invaluable.

As I’ve been learning, within the context of the larger project on American government centers, the Hawai‘i Capital Historic District possesses both distinct similarities and differences. Like other major government centers in Boston, Albany, Chicago, New Orleans, Santa Ana (California), and Scottsdale (Arizona), Honolulu’s complex extended existing government districts, rather than relocate elsewhere, and involved significant urban renewal clearance of obsolete, commercial and residential structures, supported by nearby downtown real estate and business interests desirous for government economic stimulation. Modernist architecture was the default style everywhere to represent a progressive contemporaneity. When different levels of government in American federalism — local, state, and federal — each independently employed their own architects, the resulting structures appear more or less unrelated to each other, in Honolulu and elsewhere.

Besides these common traits, Honolulu’s Civic Center also possesses certain distinctive characteristics. The newest state, Hawai’i’s Capital District is also the most reflective of its history, incorporating its royal structures, unique in the United States, whose preservation, especially of the Iolani Barracks, was one of the most heated episodes of the District’s history. Particular to Hawai‘i, too, were the roles of official advisory bodies that included multi-ethnic participants and perspectives, which led to the preservation of the Palace and the relocation and reconstruction of the Barracks.

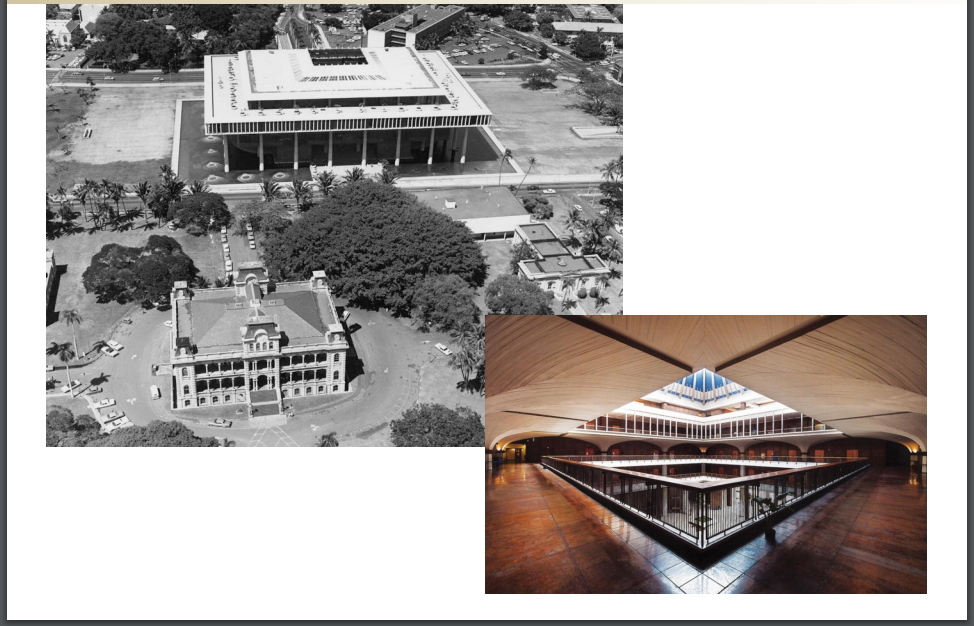

Visually, the Iolani Palace and its monumental banyan tree mask the main axis up from the harbor to the new State Capitol, which anywhere else would have been left clear. Yet this veiling works in the overall, picturesque, park-like setting of the Civic Center, master planned by the California firm of John Carl Warnecke, which also designed the Hawai‘i State Capitol. Nearly every other postwar government center mentioned earlier, featured paved plazas and open vistas, along European piazza models. Hawai‘i chose to retain and expand the existing park setting of the Iolani Palace, also deemed climatically appropriate.

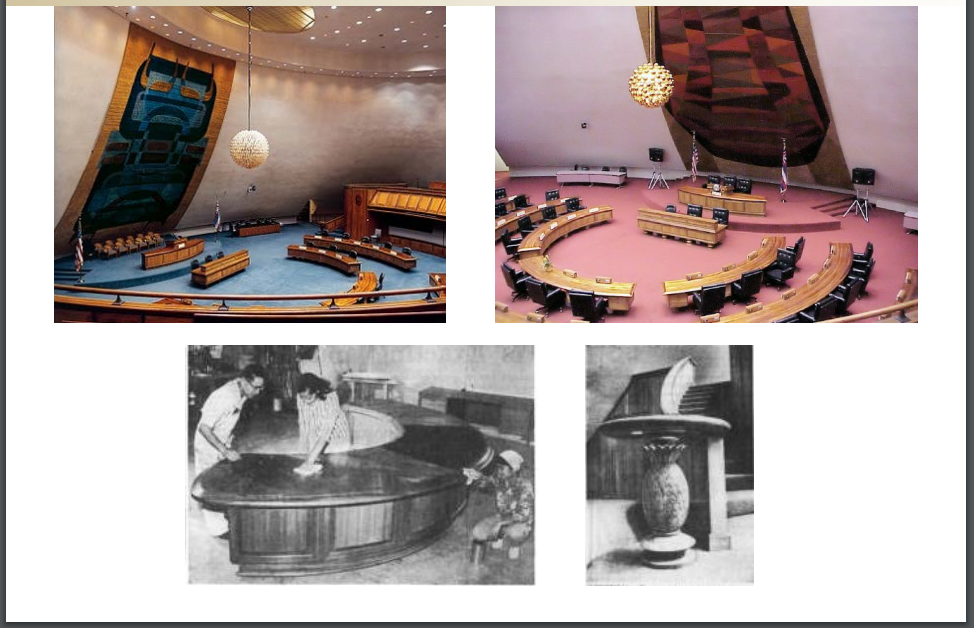

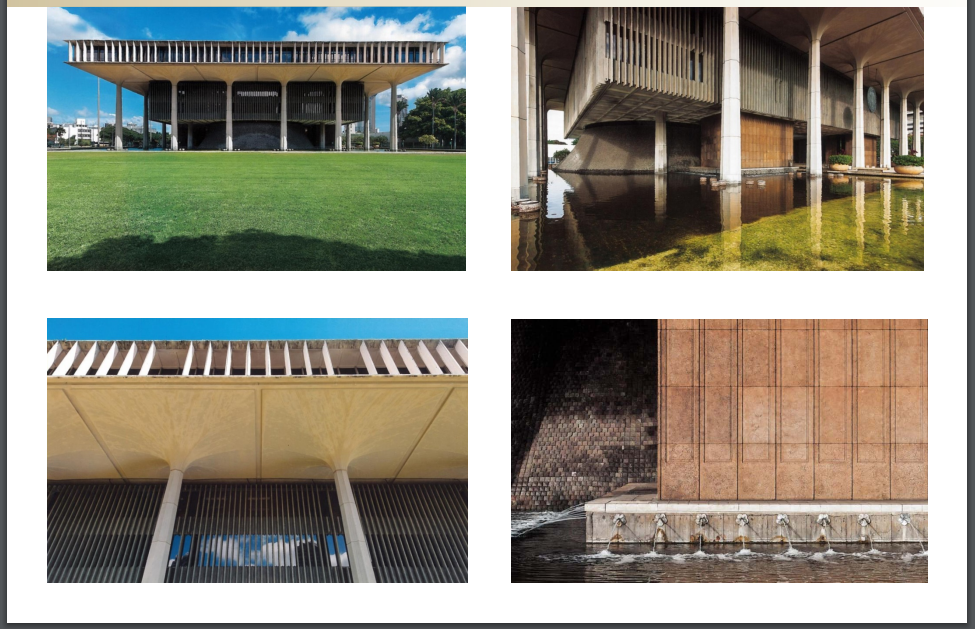

Hawai‘i’s modernist State Capitol itself is also unusually legible in its intended symbolism, compared to other abstract, modern government buildings. Historic Hawai’i Foundation’s Kiersten Faulkner demonstrated this when she introduced the Democracy by Design Symposium with slides of people’s “Favorite Features” of the building being the valued and well-understood architectural metaphors for the Hawaiian islands, palm trees, and volcanoes, as well as for American democratic openness, permeability, and transparency.

Going forward, I hope to integrate more fully the Honolulu Civic Center and its architecture into the overall story of American government centers as well as learn more about some of the Civic Center’s other main 1970s structures: the Federal Prince Kuhio Building by AHL; the Municipal Fasi Building by Naramore, Bain, Brady, and Johnson of Seattle; and the State Kalanimoku Building by Shoso Kagawa & Associates.

Editor’s Note: A free symposium in honor of the 50th anniversary of the opening of the Hawai‘i State Capitol was held on March 16, 2019 at the Capitol auditorium. Democracy by Design was the theme, exploring the role of design in fostering open government and democratic engagement. View the Symposium recordings and presentation slides HERE.

View the Hawai‘i Capital Historic District Historic Register Nomination HERE.

This article is submitted as part of a periodic series in which beneficiaries of HHF’s programs and activities share how their participation made an impact on their professional work, community service, educational attainment or personal enjoyment.

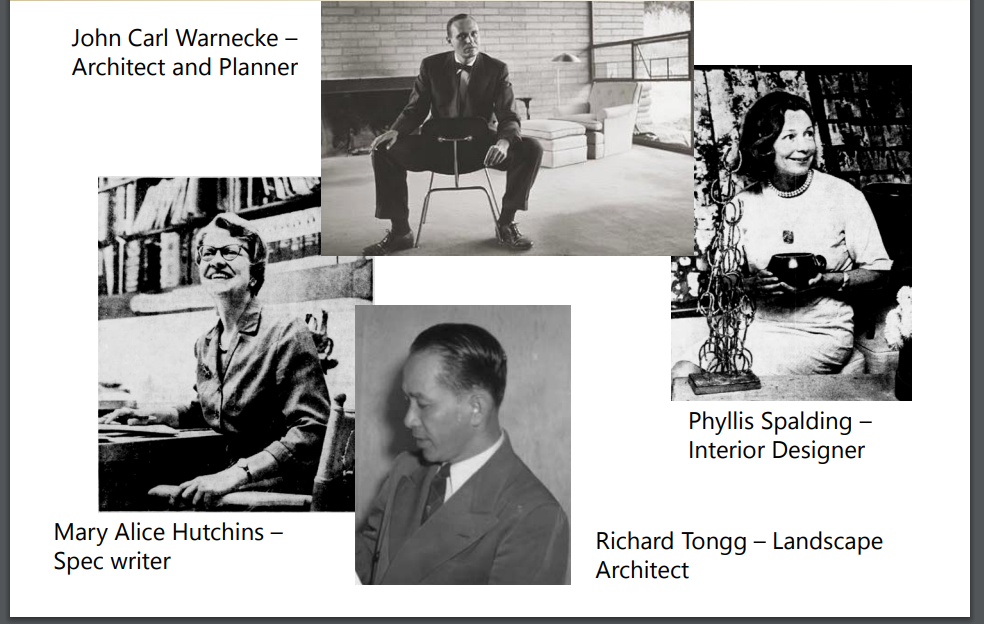

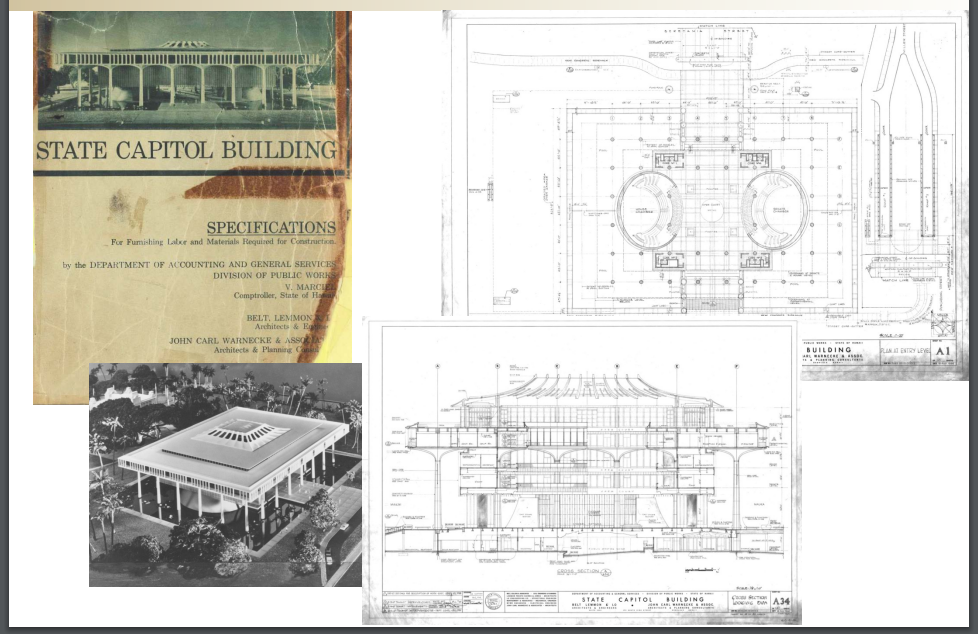

Images, top and below, are from AHL’s Symposium presentation.