If you follow the Rearview Mirror column in the Honolulu Star-Advertiser, you’re likely to be aware that columnist Bob Sigall regularly invites his readers to share their personal memories of places and times of yesteryear.

Last week, Sigall issued a call for recollections about Honolulu’s Hell’s Half Acre and Tin Can Alley, two residential areas next to downtown Honolulu where about 17,000 people resided until the 1960s. The dense neighborhoods were filled with lower-income housing punctuated by chop suey houses, cafes, beer parlors, movie theaters, a dance hall and a variety of shops. From the 1950s the area fell victim to redevelopment, in spite of resistance by preservation groups led by Nancy Bannick who argued that the two areas were significant representations of Honolulu’s unique history and culture.

Rearview Mirror: Remembering Honolulu’s Hell’s Half Acre, Tin Can Alley

By Bob Sigall

3/18/22: I’m sure most of my readers could point to where such O‘ahu neighborhoods as Waipahu, Pālama, Mānoa or Kapahulu are.

But what about Hell’s Half Acre or Tin Can Alley? Do you remember them? Eighty years ago, one-eighth of Honolulu’s population lived in them, and most everyone else knew where they were. Rents there were cheap, and you could walk to a downtown job in five to 10 minutes.

Ray Iwamoto asked me recently about the two areas. “I wonder if you could research exactly where Hell’s Half Acre and Tin Can Alley were,” he said.

“I grew up on River Street near Hotel (Diamond Head of Nu‘uanu Stream), and I thought Hell’s Half Acre was also Diamond Head of Nu‘uanu Stream.

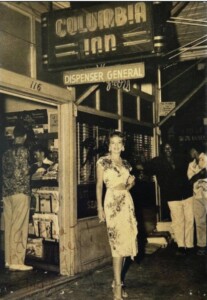

“I thought it might have been near Beretania and River and not in the Hall Street area. I also thought Beretania Follies was either in or near Hell’s Half Acre. The original Columbia Inn was nearby.”

From the 1880s to the 1960s, the area mauka of Beretania Street and up to Vineyard Boulevard was filled with low-income tenement housing. About 17,000 people, or about one-eighth of Honolulu’s 1936 population, lived in the two areas. Families could rent a three-room home for $10-$20 month. Kitchen facilities and toilets were generally outside.

From Liliha Street east to Nu‘uanu Stream was an area called Hell’s Half Acre.

From Nu‘uanu Stream continuing east to about Nu‘uanu Avenue, it was called Tin Can Alley.

Hell’s Half Acre is a term used across the United States and dates to at least 1830. Tin Can Alley may be a variation of Tin Pan Alley, a New York City region housing several music publishers and songwriters.

In 1936, a Honolulu Star-Bulletin article said, in the Tin Can Alley area, there were many thriving small businesses: five chop suey houses, 21 cafes, 11 beer parlors, two poolrooms, two movie theaters, a toy store, dance hall, five jewelry stores, two meat markets, 16 dry goods stores, one doctor and three liquor stores.

Alvin Yee, who grew up in the area, said Hell’s Half Acre was not as crime-ridden as its name implies. “I believe its name is a corruption of Hall Street, which once curved from Kukui Street to North Beretania Street, parallel to A‘ala Lane, which was straightened out during the redevelopment of the 1960s.

“Hell’s Half Acre was the community approximately between Liliha to College Walk. The Japanese temple now located at College Walk was located next door to my tenement home, but was moved to its present location in the late 1960s.”

Yee is talking about the lzumo Taisha shrine. Dozens of Japanese tourists visit it daily. It is one of the few Shinto shrines in the U.S. The first permanent structure dates to 1922, and it was moved to its current site in 1968.

“Tin Can Alley was primarily Kamanuwai Lane,” Yee continues. “The new portion of Maunakea Street from Beretania to Vineyard streets was laid in increments during the 1960s and was called Maunakea Extension.

“If one stands at the Chinese Cultural Plaza’s corner on Beretania Street, that is the approximate original location of Columbia Inn, which opened for business in December 1941.

“Look mauka and observe how the roadway declines gently, then levels off. Where it levels off and on the right was the location of the Beretania Follies theater, about where Honolulu Towers’ driveway is now located.

“Kamanuwai Lane then forked leftward through a residential area and ended about where Pauoa Stream emptied into Nuuanu Stream, just makai of Kukui Street.”

The movie “Hell’s Half Acre” was filmed in 1953. It traces a woman who is looking for her husband, who died in the Dec. 7, 1941, attack, she is told. She finds him alive and living under an assumed name, and engaged in criminal activities in Hell’s Half Acre.

‘The Gem in the Slums’

“The original Columbia Inn was located at 116 N. Beretania St.,” Gene Kaneshiro told me, “at the corner of Beretania and Maunakea streets, aka Tin Can Alley.”

“My dad, Tosh Kaneshiro, and his brother Frank opened Columbia Inn in 1941. At the time, Tosh referred to Columbia Inn, as ‘The Gem in the Slums.”‘

Gene Kaneshiro said “Hell’s Half Acre’s” location producer visited Columbia Inn while scouting the area. He wrote to ask whether Columbia Inn would close every evening after 8 p.m. to feed the cast and crew for the duration of the 1953 filming.

“The location producer’s letter was addressed, ‘The Gem in the Slums’ Honolulu, Hawaii.’ The Honolulu Post Office delivered it.

‘Tosh accepted the offer and fed actors such as Wendell Corey and Evelyn Keyes and the crew.”

Chinatown festivities

Gene Kaneshiro also told me he remembered Chinese New Year celebrations in the area in the mid-1950s.

“When I was 9-12 years old, the Chinatown New Year celebration was an event that was planned by the many Chinese societies and clubs who had cultural functions such as music, dance and mahjong.

“There were many clubs of Chinese martial arts with masters teaching different styles, which included the traditional lion dance.

“The original Columbia Inn, The Gem in the Slums,’ where the Chinese Cultural Center is today, organized a coming together of all of the clubs’ lions, musical groups (drums, cymbals and gongs), and martial arts masters and their students in front of our restaurant.

“He borrowed a flatbed truck from a produce company, decorated it with coconut fronds and flowers, attached some floodlights on the telephone pole, purchased a 100-foot-long string of firecrackers, ‘hired’ the Honolulu Fire Department’s hook and ladder truck from the Central Fire Station (I recall seeing five cases of beer on the running board) to stage a finale to the evening’s festivities.

“After parading and visiting the many Chinatown businesses, each club brought their lion and ensemble to the restaurant.

“Each martial arts master and their chosen students performed, and the finale was the lighting of the 100-foot firecracker, right in the middle of Beretania Street. Thousands of spectators gathered, covering the entire intersection of Beretania Street, Maunakea Street and Kamanuwai Lane.

“Beretania Street was closed to traffic, albeit by default. He did all that without a permit…because it could be done and it was fun! Those were the days.”

In the 1950s and 1960s, the city tore down the tenements and built Kukui Gardens, the Chinese Cultural Center and many condominiums and stores.

Preservation groups, led by Nancy Bannick, tried to slow them down. Many of the buildings were historic and told the story of “old Honolulu,” she said. They were a collection of architectural treasures and curiosities that we needed to keep Honolulu distinctive. They were significant symbols of our city’s history and culture.

It was futile. The areas called Hell’s Half Acre and Tin Can Alley were bulldozed and shiny new buildings erected in their place. They can now be seen only in our collective rearview mirrors.

The Rearview Mirror Insider is Bob Sigall’s twice-weekly free email newsletter that gives readers behind-the-scenes background, stories that wouldn’t fit in the column, and lots of interesting details. Join and be an Insider at RearviewMirrorlnsider.com.

Reprinted with permission from the author.

Additional resources:

In 2019, the John Young Museum of Art at University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa presented an exhibit of the photography of Francis Haar who lived in Honolulu until his death in 1960. His photos captured changes to the ʻAʻala (known today as Chinatown) during the 1960s. Also see: Francis Haar’s Documentation of a Changing Urban Community by John Williams.

Join HHF on April 7, 2022 for a presentation and panel discussion about The Preservation of the Nancy Bannick Collection at the Hawai‘i State Archives including a slideshow of Bannick’s photographs of old Hawai‘i.