This post is a transcript of the interview, “Leading Preservation Architect Takes Us on a Historical Tour of Chinatown” by journalist Noe Tanigawa which aired on Hawaii Public Radio’s The Aloha Friday Conversation on January, 28, 2022. The transcript is printed with her permission.

Noe Tanigawa: Glenn Mason is the principal at MASON Architects in Honolulu. They’ve got offices on Merchant Street and specialize in historic preservation.

Mason is also an American Institute of Architects Fellow and has worked on many of Hawaiʻi’s most important historic sites such as ʻIolani Palace and Kawaiahaʻo Church. He agreed to take us on a tour of Chinatown to open our eyes to some of its charms.

Glenn Mason: We moved into Chinatown in 1982. When we moved there, (chuckles) I’m not sure it was at its nadir, but it was pretty low-down. About a year after we moved into Chinatown the last restaurant that was open in all of downtown Honolulu closed. And for one year there was not a single restaurant open in Chinatown or downtown at night.

NT: Are you kidding?!

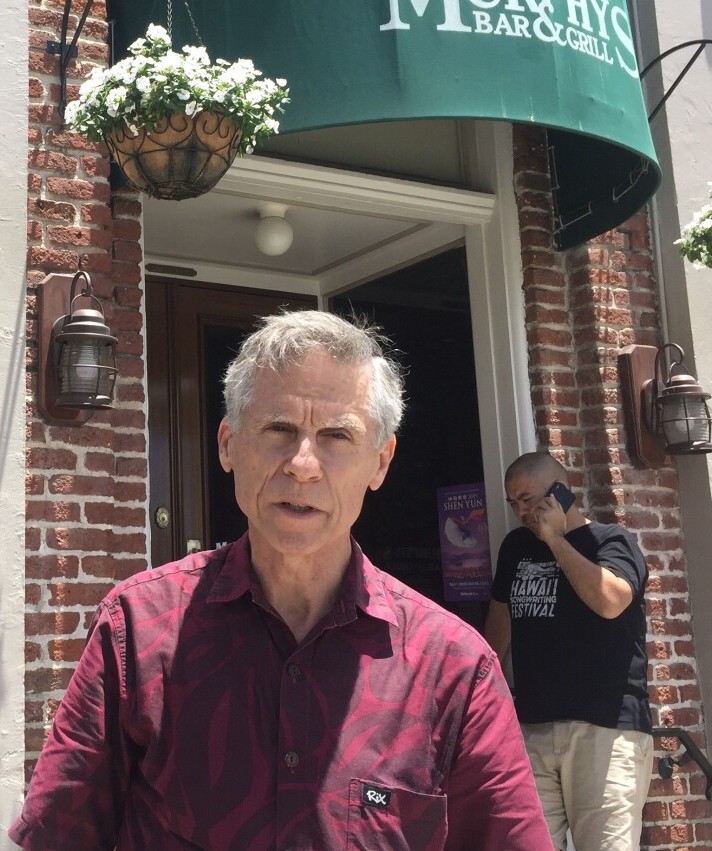

Local architect Glenn Mason in front of Murphy’s Bar & Grill © Noe Tanigawa, HPR

GM: It’s hard to believe. This was probably ’83, maybe ’84. There were no restaurants open at night. None.

Chinatown developed primarily because of the harbor. It was very harbor-oriented at the time it was developed.

So, we are right…when you get to where Murphy’s is, that’s in Chinatown.

NT: Ah ha.

GM: So now we’ve just walked into Chinatown.

(NT giggles)

GM: Murphy’s has this–they’ve got all these Chinese pavers. They’re granite, they’re probably about four inches thick, set as pavement. These came over as ballast in ships from China because in the very beginning we were shipping out lots of things like sandalwood, we basically raped our forests, in order to get sandalwood to ship to the East and when the ships came back they were empty and one of the things that they did was they used stones as ballast when they came back. This is all left over from the pre-1900 paving.

The Nippu Jiji Building © Joel Bradshaw via Wikimedia Commons.

This is called the Foster Block actually.

NT: Wow, the Foster Block with O’Tooles there, the Nippu Jiji Building.

GM: Exactly. That entire brick building and the small bldg. behind it actually survived the fire. This is as far down as the fire got. There was a terrible fire in 1886 and then another one in 1900. As a result, many of the buildings that were built after 1900 were built with brick or stone. Most of the buildings that we’re looking date in Chinatown date from that time period. Now they built some wood buildings at the same time because they were cheap, they were easy to put up. Almost all, maybe all of those buildings, are gone now.

So, the remarkable thing about Chinatown is its scale. I mean, almost every building is two stories. There’s a few three-story buildings, and an occasional building that’s four stories, except for the newer developments that the City has made with, by inserting housing into Chinatown, which actually is a good trade off because it actually brought life back into Chinatown. I mean, before there was a substantial amount of housing in Chinatown, it was dead at night. I mean there just wasn’t very much…Except again when we moved into Chinatown there probably six porno movie theaters or porno arcades in Chinatown and t was a place that people went for bars, to drink, and find drugs, or go to porno movie theaters. And so that was it. Now you walk around and you don’t see any of that which is great.

NT: Aww…

GM: And lot of that came from not only individual developers coming in and fixing up buildings, but I do attribute some of it to the City bringing people into Chinatown, people who live in Chinatown.

NT: That was what they trying to do, right?

GM: Exactly.

NT: They got HUD money to put people right there in the Gateway Plaza.

GM: Well, every one of the City’s projects where they’ve developed these high-rise housing areas, or even mid-range housing, those were parking lots. Harbor Court was a parking lot. It actually, believe it or not, Harbor Court, that site, when they did the archaeological investigations they found that that site was the site of Kamehameha the First’s house site when he was on O‘ahu. The history of the use of this harbor goes back at least a couple hundred years that we know of.

NT: When they built these buildings what are they in the style of?

GM: Well, I think you have to look at eras. Let’s assume that you look at things from the time of the fire on. For the next 25-30 years, people were building buildings that looked like buildings elsewhere in the United States.

Wo Fat Building circa 2018 HHF photo.

Starting in the mid-20s there was a very strong drive to try to come up with an architecture, a design style that was individual to Hawai‘i, called Hawaiian Regionalism. And there are buildings in Chinatown like Wo Fats which definitely try to say, we’re unique to Hawai‘i, we’re unique to this place.

![]()

![]()

The thing is that you know, we call it Chinatown, and of course it had a very high proportion of Chinese Chinese living in it and working in it. But the peak of Chinese residents in Chinatown was probably fifty-six percent right after the fire, and then of course it decreased gradually from that point on. And today when you walk you around Chinatown it’s filled with Vietnamese and Filipinos and…I mean the food itself is from all over, it’s all over the Pacific and so you know that’s just the nature of Chinatown. It’s always been a center for non-native community, I think if you want to call it that.

One of the things that I think is really important to talk about, and this is partially my interpretation; what makes Chinatown special is scale, of course the history, but how does the history get expressed? We tend to think of historic districts like this as individual buildings and that’s not really what it’s about. It’s about the buildings, but it’s also about the street pattern, the view planes and everything else. It’s a composite of everything.

We’re walking along here under a canopy. There are blocks in Chinatown you can walk around the entire block when it’s pouring rain and not get wet. This is a characteristic of Chinatown.

NT: Oh, you’re right, it makes it so nice to walk up this street. We’re not in the sun!

GM: Right, we’re not in the sun, and when it’s raining we’re protected. When you look around, that’s a characteristic of Chinatown, right? Again it’s everything, lava rock curb stones and I can see the mountains looking up Nu‘uanu Avenue. That’s important.

NT: I can see the ocean! I see the harbor!

GM: Right. Exactly!

NT: On this one street I see the harbor, the ocean and I see the mountains.

GM: That’s so easily lost with the design of canopies. You see the break in the decorative element at the edge there. These canopies were designed at a time when everything was a little shorter. So now they have great big delivery trucks that come by and they bang into the canopies. The canopies extend out to and sometimes even slightly beyond the curb, but do you want to whack them all back?

By and large what’s happened is the building owners in Chinatown have really fixed up their properties. I mean you go in Brick Fire Tavern, and all these places we’re coming up here, they’re pretty nice buildings. The owners have done a really nice job fixing up the buildings on the inside and so I’m actually very optimistic.

NT: What is with this bizarre Chinatown architecture where you go inside the building, you walk up two floors towards the back, you come out to a veranda over a garden. What kind of Chinatown architecture is this?

GM: Oh yeah. Look, if the lot is big enough, remember all of these buildings were designed to be naturally ventilated, they couldn’t be big blocks of buildings and so they’re all relatively thin. If you have a deep lot, you’re not going to build the building the full depth of the lot because then you’ll have no air. When you look at a building like the Mendonca Building that has a nice courtyard, that courtyard was built partially because after about fifty feet deep you have no ventilation. And so, all the buildings that were built in downtown Honolulu and elsewhere, they all tried to say relatively thin and that’s the only way that human comfort was even remotely possible until we air conditioned the living daylights out of everything.

Again, there was not a lot of creative architecture here. People were building buildings that were kind of, I would just say, normal buildings. But there’s a certain amount of, the modularity of brick, the modularity of stone…

NT: What do you mean by modularity?

GM: Well, one of the nice things about brick is that the shape and size of brick is a module that’s very easy to understand and grasp and, um, or even a stone that’s a little bit larger, that modularity creates a certain texture that is more human scale than a building of plaster that’s completely plastered flat. I think that modularity that is expressed in brick and stone and some other materials is actually one of the things that appeals to people. It gives a building a certain texture.

Slate Pavers on Hotel Steer are remnants from the 1800s © Noe Tanigawa, HPR.

The scale is not only the height of the buildings, it’s the scale and modularity of the materials they’re made out of. Even the sidewalks, when you look at…this is actually the only–we’re standing outside of the old Club Hubba Hubba building—it’s is the only place where there’s actually a remnant slate sidewalk, and it goes back to the old Chinese granite pavers.

NT: You know you’re pointing out to me also that there’re so many textures that I’m seeing here and you know they’re worn; they’re not brand spankin’ new.

GM: One of things about Chinatown, even the signage in Chinatown is much more exuberant. Part of that is that you have all these different storefronts one after another, right? But part of it is,–that’s the nature of Chinatown. I’m hoping that eventually more of the signs will be saved because they tell the history of the place, again as much as the buildings do.

NT: Yeah!

GM: There are all these little things, idiosyncratic things, they’re interesting, but they lend depth to our existence, frankly…and that depth, that knowledge about our past is really important.

I don’t care whether you’re talking about Hawaiian history, or the history of Japanese in Hawai‘i, or the history of Chinese in Hawaii, all of that layers together to create the place that we live in. And if we don’t, if we’re not sensitive to this stuff, then I mean, why are we here? We aren’t New York City, we aren’t even San Francisco, you know, we are our own place. I think knowing the history of this place and why it, you know, what’s special about it is really important to understanding who we are.

Maybe it’s a biased view. Anyway, it’s just kind of interesting.

NT: What would you call the center of downtown?

GM: I think Bishop Street is the center of downtown, but I mean…

NT: So, would you say Bishop and King?

GM: Oh, if you had to pick a spot? Yeah, I’d probably pick that. You’d have to pick that intersection because it’s the intersection of the two major streets in Honolulu and also I mean some major public open spaces focus on that space.

That’s true, but I mean clearly the civic center is the center of government in Honolulu and it always has been. I mean that area between Mission Houses and really Richards Street is where our government has been focused. You have Kawaiahao Church, it’s a National Historic Landmark, the first missionaries were there, and it goes all the way up through Statehood and today being an important government center. You have Washington Place that Lili‘uokalani lived in; you have St. Andrew’s Cathedral which started in 1864. When you start to look at the age of the buildings and what they represent, that civic center is huge in our history.

We just celebrated the 50th anniversary of the building of the State Capitol. That’s 50 years old. That’s the threshold typically for determining a historic building. And that thing, that has been there for 50 years. If you look at and think about all the other buildings in the civic center, it’s actually a wonderful environment to walk around in and to talk about because the architecture that is in our civic center is really very interesting.

NT: Really? Is it something to be proud of?

GM: Oh I think so…Yeah! I don’t care what you’re interested in, whether it’s architecture, social history or political history, our civic center actually has it all.

NT: Glenn Mason of MASON Architects in Honolulu led us gallantly through Chinatown and on to ‘Iolani Palace.

Further reading and listening:

In 2016, HHF gave a special tour of some Chinatown’s beautifully renovated and repurposed buildings. See photos of the tour: Chinatown Upstairs: An Exclusive Discovery of History, Architecture & Food

Chinatown Historic District National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form

The Aloha Friday Conversation: A tour of Chinatown and Iolani Palace

- Anton Krucky, the director of the Honolulu City & County Department of Community Services, explains the strategy for improving conditions in Chinatown | Downtown-Chinatown NB Meeting | Full Article

- ʻIolani Palace’s historian Zita Cup Choy takes us back to the 1890s when Honolulu was a bustling international seaport | White Glove Tour | Full Segment

- Mark Gabbay, an investment manager on Kauaʻi, discusses the art center he’s developing in Līhuʻe | Full Segment