By Donne Dawson, HHF Trustee

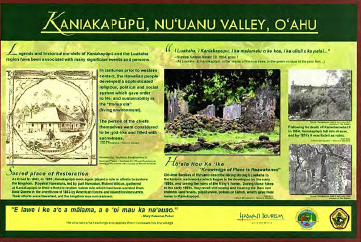

At this year’s Preservation Honor Awards, Historic Hawai‘i Foundation honored a protection measures project installed at the beloved and very fragile Kaniakapūpū, the 176-year-old summer home in Nu‘uanu Valley of King Kamehameha III, Kauikeaouli, and his queen, Kalama.

Kauikeaouli was the second son of Kamehameha the Great and the longest reigning monarch in the Hawaiian Kingdom. His majestic 12-foot tall statue stands today in Thomas Square in Honolulu in honor of Lā Ho‘i Ho‘i Ea, one of the first national holidays of the Hawaiian Kingdom when Admiral Richard Thomas was sent by England’s Queen Victoria to restore the Hawaiian Kingdom after rogue agents of the British Crown temporarily seized control of the Hawaiian government. Kauikeaouli proclaimed these now famous words, Ua mau ke Ea o ka ‘āina i ka pono, “the sovereignty of the Hawaiian Nation is restored by righteousness,” as the Hae Hawai‘i, the Hawaiian flag, was raised again supplanting the Union Jack. A lū’au is said to have happened at Kaniakapūpū where 10,000 people marched up Nu‘uanu Valley to the King’s summer estate to celebrate the return of the Hawaiian Kingdom. Since Kaniakapūpū was built prior to the lush Nu‘uanu forest we know today, it’s likely that the giant Hae Hawai‘i–atop what was probably a 100-foot flagpole–was the most prominent feature of the 18-acre site, visible from Honolulu Harbor a mere 4 ½ miles away.

The Preservation Award was given to Kaniakapūpū in recognition of recent mitigating efforts by the State Department of Land and Natural Resources’ Division of Forestry and Wildlife; Honua Consulting, LLC; Omizu Architecture and ‘Ahahui Mālama o Kaniakapūpū—kahu ‘āina of the area led by Dr. Baron Ching, Kapukini Kalahiki, Dr. Lynette Cruz and others who are intent on protecting and preserving the site that has endured so much over the years.

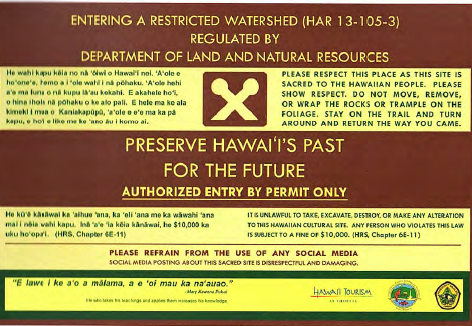

As an effort to prevent trespassing at Kaniakapūpū, the project included included installation of pathways, signage, and felling of large trees that are considered threats to the historic structure and site features. Kapu signage was mounted near the entrance to indicate that the area is a restricted site regulated by the State Department of Land and Natural Resources and access is available by permit only. Additional signage near the actual ruins explain the archaeological, historic and cultural significance of Kaniakapūpū to prompt a sense of respect and caution and to deter further loitering and damage to the ruins.

Kaniakapūpū is listed on the State and National Register of Historic Places. It is also situated within Restricted Watershed and by law is closed to the public. The cottage structure itself at Kaniakapūpū was constructed from 1843-1845, however, some features on the property may date as far back as the pre-contact era. As the nomination reads, “Kaniakapūpū has maintained high integrity for its location overlooking Nu‘uanu Valley, its complex architectural design which molded both traditional Hawaiian aspects as well as foreign architectural elements, the preserved setting on undeveloped land, original materials, high craftsmanship, a feeling of lasting Hawaiian history and culture, and an association with high ranking members of Hawaiian society and history.”

Hard to believe that it was 50 years ago that I first visited Kaniakapūpū as a young child with my mother. Growing up less than half a mile from this wahi kapu or sacred place, I’ve always felt a kuleana to protect it. Over the years I have witnessed the natural degradation of the site due to the passage of time, but most alarming has been seeing the dramatic increase of visitors over the years, most of whom are tourists who show no appreciation for the fragile structure or its significance to our people and our culture.

I’ve had to step out of my comfort zone more than once to reprimand children for climbing on the already crumbling walls of the Kaniakapūpū structure while their parents ignore such behavior. I’ve also seen the aftermath of graffiti spray painted on the walls of the sacred structure and have cleaned areas where inappropriate “gifts” have been left at the site like random food items, rocks wrapped in ti leaves or orchid lei with plastic ribbons that looked like they were left over from someone’s arrival at the airport. Well-intentioned as these gifts might be, leaving them there at the foot of this sacred place encourages others to do the same. I’ve even discouraged people over the years who have stopped me on the road asking for “directions to the ruins” in an effort to spare Kaniakapūpū from one more group of tourists.

Dr. Baron Ching, an internal medicine physician, takes protection a step further–a huge step further. Whenever he holds a service day to mālama Kaniakapūpū on the first Sunday of each month, he uninhibitedly ropes in unassuming visitors to lend a hand as they wander into the area.

“Hey you, did you know you guys are illegal?” He brusquely shouts out to folks looking at the posted warnings and interpretive signage. “You wanna GET legal? Then you gotta work!”

Dr. Baron Ching sharing the history of the site while visitors help care for it. Photo courtesy Donne Dawson.

In the two hours that I was there observing his tactics, I witnessed 4-5 small groups of visitors, totaling about 25 people, pick up gardening tools that Dr. Ching had on site and follow his instructions on what to do, all the while listening to his stories about the history and significance of this place. Not one person responded negatively or walked away. They all pitched in to work. Dr. Ching learned much of what he knows from the late Mel Kalahiki.

The Sunday I also met Uncle Mel’s granddaughter Kapukini Kalahiki and her three boys– Nathanael, Roman and Matthias–who came to work as well. “I come up here not knowing anything,” Kalahiki says. “(Baron) teaches me stuff and I teach my kids stuff.” (Truth is, Kapukini knows a ton, from all the years coming to Kaniakapūpū with her grandpa Mel since she was a young child.) “Literally (Baron) is my source right now,” Kapukini says. “He passes his knowledge to everyone who comes through here…People are getting educated.”

Trisha Kehaulani Watson PhD, a cultural consultant who nominated the protection project for a Preservation Award, says education is the key. She, too, feels a strong sense of kuleana to preserve and protect this sacred site.

“The selfishness and disrespect I have witnessed over the years is truly painful,” Watson says. “As a people, we Hawaiians have already lost so much. We must preserve what we have left and create opportunities to learn from these sites and restore them. We must move toward restoring customary practices at sacred sites in a manner that is both consistent with tradition and mindful of our living culture.”

“As a home to our beloved ali‘i, there is an exceptional importance to this site,” continues Watson. “It was selected by our kūpuna with great intention. The stones throughout the site were placed with great care. As lifelong learners, we still have so much to learn from and about this site. This is why any damage to the structures or displacement of features is so destructive to both the tangible and intangible elements of the landscape. Any time a feature is modified or destroyed it’s like we are burning down a wing of a library.”

Ryan Peralta, Forest Management Supervisor for the DLNR’s Forestry Division also feels a special kuleana for Kaniakapūpū. The site falls under DLNR’s jurisdiction and Peralta also has family connections in Nu‘uanu Valley that date back decades. Peralta shares the frustration that even though the area is Restricted Watershed and closed to the public, visitors continue to come in disconcertingly high numbers.

“To protect Kaniakapūpū, DLNR’s Forestry Division installed some ‘Kapu’ signage,” Peralta says. “However, as people constantly disregard the ‘Do Not Enter’ signs we had to install low-impact barriers made out of natural materials around the site itself to encourage people to stay on the footpath and view the structure from a distance. We installed informational and educational signs to educate visitors about the significance of the site to instill a sense of respect in the visitors and to help protect against vandalism and disrespectful behavior.”

Kapu signage at the site entrance and interpretive markers help improve awareness and discourage trespassing. Photos courtesy Honua Consulting.

So what does the future hold for Kaniakapūpū in light of all this damaging exposure to the public? All of these committed preservationists have ideas that separately and collectively help protect the fragile site for future generations while limiting the number of visitors.

Most immediately, Dr. Ching would like to see a protective cover over the site to protect against further weather erosion. Falling trees in close proximity of Kaniakapūpū have already taken down large portions of the crumbling structure. There’s another very tall dead tree that is precariously close to the structure and will take down another corner of Kaniakapūpū during the next big storm if some preemptive action is not taken.

If money were not an issue, Watson would like to see the entire site surveyed, mapped, and fully restored. “I’d want to see the boundaries of the site extended throughout more of the watershed such that it reflected the traditional cultural landscape that is Kaniakapūpū and Luakaha. I’d make it a cultural preserve and protected area that was closed to recreation or the public but open and welcoming to cultural practitioners and those who want to work with us to mālama the area. I’d love to see regular enforcement as part of the site management and substantial fines for trespassers and vandals with the funding from these fines going to the ongoing care and preservation of the site. And I’d love to see title for the entire watershed turned over to a Hawaiian organization dedicated to protecting and managing the site, as well as uplifting the legacies of Keaweaweʻula Kīwalaʻō Kauikeaouli Kaleiopapa and his Queen Kalama.”

Ryan Peralta would like to use digital technology and creativity to protect Kaniakapūpū. He has the excellent idea to create a virtual tour of the actual site in its present-day condition. To further enrich that experience (and create something that in-person visitors cannot see), it would be great if that virtual tour could include augmented reality or architectural rendering of what Kaniakapūpū and the surrounding area looked like when it was first constructed nearly 180 years ago. Peralta is enthusiastic about the prospect of people being able to “visit” Kaniakapūpū without actually going there. “This is an important piece of Hawai‘i’s history and the history of the Hawaiian people,” Peralta says. “Not everything is meant for us to have, hold, touch, and feel. One’s desire to experience Kaniakapūpū and share it on social media may not be in the best interest of Kaniakapūpū, its protection and its symbolic value to the Hawaiian people who have endured so much.”

Kapukini Kalahiki puts it this way: “We need these places for our children to come and see, so they know that our history is real; so they know that these people actually lived here. If we lose (Kaniakapūpū) then it’s just a story. This is an actual physical piece of our history that is still here,” Kalahiki says. “For us to educate people and then they want to visit because they want to care for this place…Now that’s the goal.”

I for one would love to see more in-flight educational videos played for visitors coming to our Islands to let them know before they seek out these sacred and fragile places and explain why we hold them so dear. That way, they can endeavor to be part of a solution rather than being party to an ongoing and growing problem.

Kapukini Kalahiki and her three sons with Dr. Baron Ching. Photo courtesy Donne Dawson.

Photo at top courtesy of Honua Consulting.

Kaniakapūpū was designated a Most Endangered Place by Historic Hawaiʻi Foundation in 2016. HHF supported stabilization efforts for the site that began in 1998. The Kaniakapūpū Site Protection Measures project received a Preservation Honor Award in 2021 for its efforts to protect the archaeological, historic and cultural significance of Kaniakapūpū.

Donne Dawson has served as a trustee of Historic Hawaiʻi Foundation since 2015. She heads the State of Hawai‘i Film Office as the state film commissioner and is a board director of Hawaiian Native Corporation, the parent organization of DAWSON. Donne served on the Preservation Honor Awards Selection Committee in 2021.