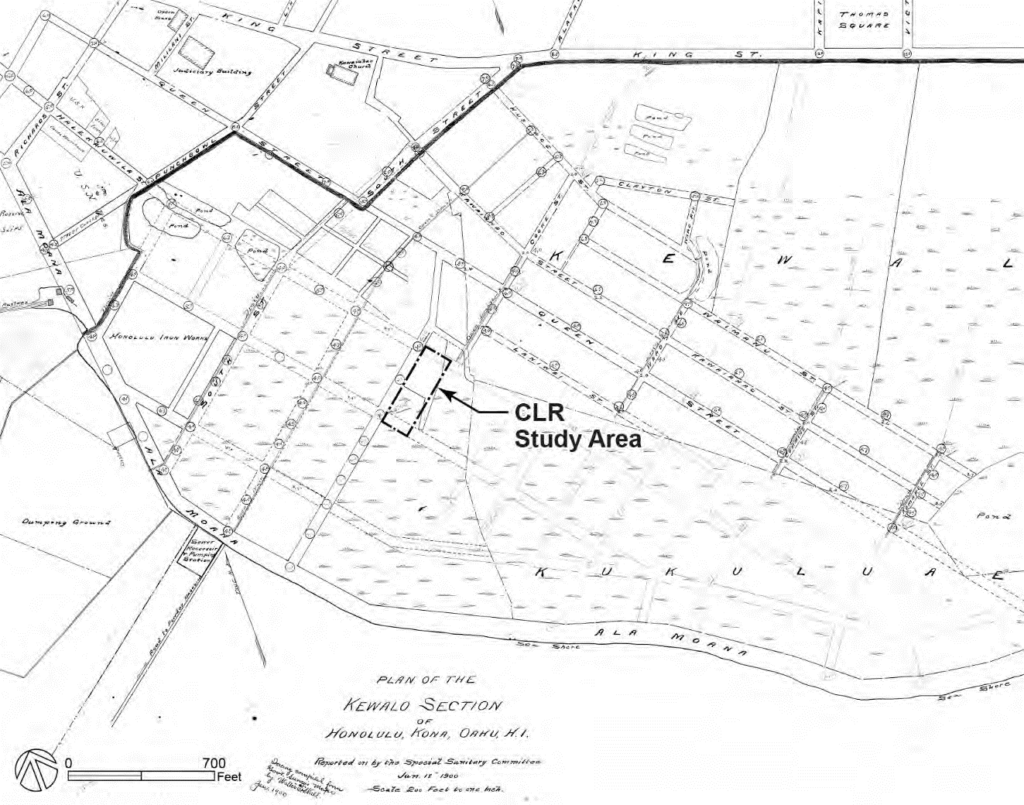

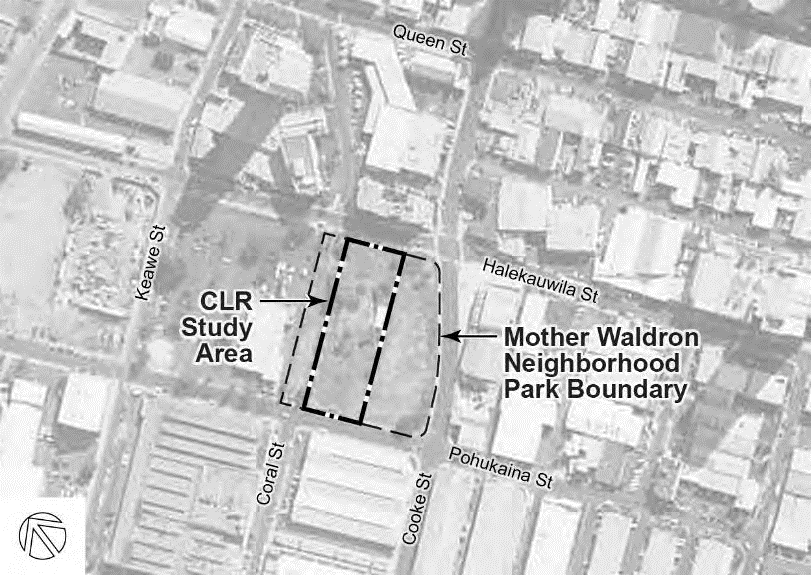

The Mother Waldron Playground Cultural Landscape Report (CLR) is a historic preservation treatment document and long-term management tool for the historically significant playground. It is one of three CLRs required by the Rail Transit’s Historic Preservation Programmatic Agreement mandated by the 1966 National Historic Preservation Act. The report was prepared by HHF Planners for the Honolulu Authority for Rapid Transportation (HART) and Jacobs (formerly CH2M) in association with the Honolulu Rail Transit Project (HRTP).

The Mother Waldron Playground Cultural Landscape Report (CLR) is a historic preservation treatment document and long-term management tool for the historically significant playground. It is one of three CLRs required by the Rail Transit’s Historic Preservation Programmatic Agreement mandated by the 1966 National Historic Preservation Act. The report was prepared by HHF Planners for the Honolulu Authority for Rapid Transportation (HART) and Jacobs (formerly CH2M) in association with the Honolulu Rail Transit Project (HRTP).

The Mother Waldron Playground CLR was recognized with a Preservation Programmatic Award as a successful documentation of the history and significance of the Mother Waldron Playground’s designed landscape and as an excellent evaluation of the site’s integrity, followed with long-term landscape treatment recommendations. The report establishes preservation goals for the playground’s cultural landscape that can serve as the basis for making sound decisions about the management, preservation treatment, and use of the site following The Secretary of Interior’s Standards for The Treatment of Historic Properties with Guidelines for the Treatment of Cultural Landscapes (1996) and other relevant provisions.

The report includes informative chapters on the historic context of the site and with the permission of HHF Planners we are delighted to share excerpts here. (Please note, the chapters are not published here in full; resource citation has been omitted.)

Excerpts from Chapter 2.0 Site History from Mother Waldron Playground Cultural Landscape Report

The physical history for this Cultural Landscape Report (CLR) is divided into three periods. These periods are defined based on changes that occurred within the Mother Waldron Playground CLR study area and its immediate surroundings, as well as larger historical trends and events that influenced the shape and form of the cultural landscape. The periods are broadly defined as follows:

- Early Land Use and Development (to 1920)

- Urbanization and Playground Development (1920 to 1950)

- Playground Renovations and Urban Redevelopment (1950-2015)

This chapter is organized chronologically by period. Each period is introduced by a narrative discussion focusing on the historic context and development known to have occurred during that period.

2.1 EARLY LAND USE AND DEVELOPMENT (TO 1920)

HISTORIC CONTEXT

Human occupation in the Hawaiian archipelago began with the arrival of Polynesians whose ancestry has been traced to the Marquesas Islands. Archaeological evidence has supported the hypothesis that Polynesians occupied and settled Hawai‘i by A.D 600.14 British sea captain James Cook’s arrival to the Hawaiian Islands in 1778 initiated the post-Contact period. The time prior to his arrival is generally referred to as the pre-Contact period.

During pre-Contact times, portions of the eight major islands of Hawai‘i existed as independent kingdoms. By right of conquest, each king bestowed control over portions of land in his jurisdiction to loyal warrior chiefs. The chiefs, in turn, granted the use and responsibilities of productivity for various lands to individuals of lower rank. By the mid-seventeenth century, Native Hawaiians were implementing a complex system of land use that divided each island into ahupua‘a. Inhabitants had access to resources within the boundaries of an ahupua‘a that might have been comprised of anywhere from a few hundred to over 100,000 acres. The ideal ahupua‘a was a wedge-shaped portion of land bounded by ridgelines or rivers that extended from the upper mountains to the sea that enabled inhabitants to have access to a full range of island resources. Ahupua‘a were often divided into ‘ili, or smaller portions of land.

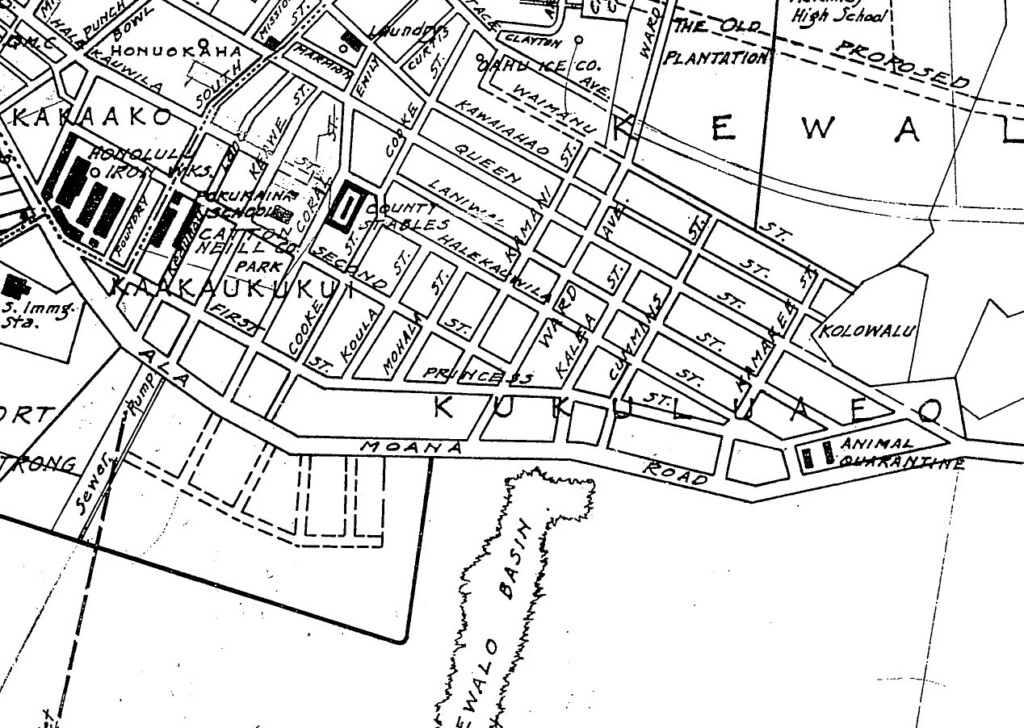

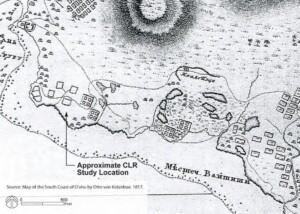

The contemporary urban district of Kaka‘ako is larger than the traditional ‘ili of the same name. Mid- nineteenth-century records indicate that “Kaka‘ako” was a relatively small ‘ili inhabited by fishermen and situated on the coastal plain between Honolulu and Waikīkī near the present day location of Punchbowl and South Streets. The CLR study area is located within the traditional boundaries of Pu‘unui and Ka‘akaukukui ‘Ili in the Makiki Ahupua‘a.

By 1795, King Kamehameha I had established sovereign authority over most of the major Hawaiian Islands and a period of relative peace prevailed. The king built royal residences at Waikīkī and Kou (close to present-day downtown Honolulu) and both areas were more densely populated than the intervening coastal plain.

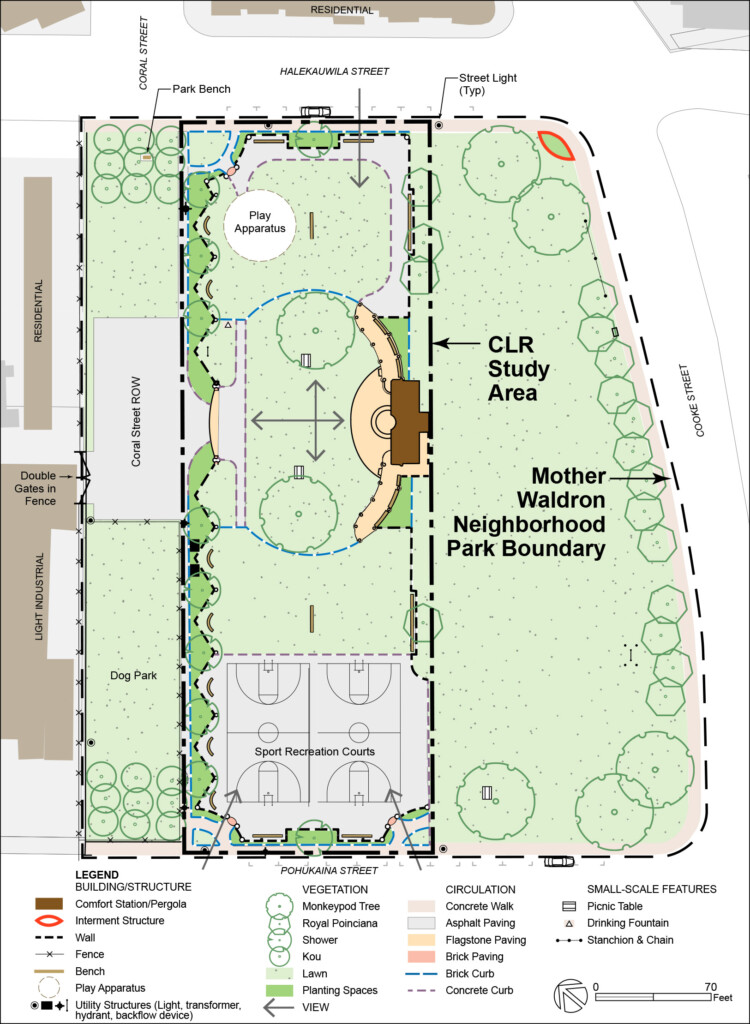

During his reign, the coastal plain between Honolulu and Waikīkī was used for “fishing, landing canoes, producing salt, cultivating taro, and practicing religion.” An 1817 map of the coastal plain between Honolulu and Waikīkī depicts a number of traditional native dwellings near the coastline, fishponds, and salt pans, as well as pedestrian trails that connected Honolulu and Waikīkī (Figure 2.1).

Figure 2.1: The coastal plain between Honolulu and Waikīkī, 1817. (Base Map: South Coast of O‘ahu, 1817, by Otto von Kotzebue. (Source: Appendix D, Cultural Impact Assessment for the Kaka‘ako Community Development District Mauka Area Plan, 2008)

Following the death of King Kamehameha I in 1819, social and cultural traditions in the Hawaiian Kingdom underwent a period of rapid change. The effect of a massive death rate among the Native Hawaiian population due to a lack of immunity to foreign diseases, coupled with the political and economic influence of foreign missionaries and other westerners, brought added pressure to bear on the monarchy for land reform to enable individual fee ownership of land.

In the mid-nineteenth century, Kamehameha III implemented a new land ownership system that was based on a capitalist system of individual fee title. Under the provisions of the Mahele of 1848, the Board of Commissioners to Quiet Land Titles awarded Land Commission Awards (LCAs) to a number of individuals. Through the Mahele process, land was apportioned between the King, the government of Hawai‘i, and various chiefs or members of the ali‘i or ruling class. The Commission also issued fee simple title land awards to a number of native tenants under the provisions of the Kuleana Act of 1850. Upon issuance of the final LCAs, the ancient land tenure system of Hawai‘i ended.

By the time of the Mahele, Honolulu had become the well-established capital of the Hawaiian Islands. The city’s boundaries had begun to include adjacent areas like Kaka‘ako, making the marginal swamp and intertidal lands of Kaka‘ako much more valuable. As a consequence, much of the acreage in Kaka‘ako was awarded to “the royal family, loyal retainers, and other important people.” By the end of the nineteenth century, however, land in the Kaka‘ako district was largely owned either by the Government of Hawai‘i or prominent people and large estate trusts including Queen Emma, Victoria Kamamalu, Bishop Estate, Victoria Ward, Magoon, and Cooke (Figure 2.2).

Figure 2.2_Land Ownership and Traditional Location of Pu‘unui and Ka‘akaukukui ‘ili, 1884. (Base Map: Map of Honolulu, Kewalo Section, S.E. Bishop, 1884. Registered Map 1090. Source: Hawai‘i State Land Survey Division)

Throughout most of the nineteenth century, Kaka‘ako remained a sparsely settled area located between the more populous central Honolulu and Waikīkī areas. However, its location near the edge of the town made it convenient for “cemeteries, burial grounds, and for the quarantine of contagious patients.” During the 1853 smallpox epidemic, patients were quarantined at a hospital in Kaka‘ako and victims were buried nearby. In 1881, a hospital and receiving station for people suspected of having Hansen’s Disease was also established. Contemporary archaeological projects in the area have documented several large cemeteries that date to Pre- and Post- Contact periods.

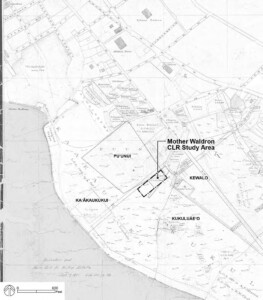

Land reclamation activities, drainage and infrastructure improvements began in the late 1800s and continued through the early twentieth century. Material dredged during the construction of the Ala Wai Canal (1928), Kewalo Basin (1929), and other near-shore projects, as well as material generated by the city garbage incinerator, continued to be used to fill low-lying and shoreline areas in Kaka‘ako. All of the ponds and low-lying areas in Kaka‘ako were filled in and additional land seaward (makai) of the beach road was created from dredged material (Figure 2.3).

Figure 2.3: Marshland, ponds, planned drainage and street system in the vicinity of CLR study area, 1900. (Base map: Kewalo Section Registered Map 1090, dated 1900)

Continued growth in Honolulu spurred changes in the Kaka‘ako district from a sparsely populated industrial area to a densely populated residential and commercial district. Kaka‘ako developed into an urbanized district comprised of small-scale wood frame dwellings and tenements, and low-rise commercial and industrial buildings. Many of the residents in the community worked as fishermen or in the nearby commercial and industrial operations, and Kaka‘ako became well known for its residential enclaves of working families of Hawaiian, Japanese, Portuguese, Filipino, and Puerto Rican descent.

The original Pohukaina School

In 1913, Pohukaina Elementary School was constructed between Coral and Keawe Streets. Kaka‘ako was a prime location for industrial operations such as the Honolulu Iron Works, lumber yards, and draying companies that needed large spaces for stables, feed lots, and wagon sheds. By 1914, the City and County of Honolulu built a public works stable across Coral Street from the elementary school, on the site that would later become Mother Waldron Playground.

PHYSICAL LANDSCAPE

Natural Features and Responses to Natural Environment

Kaka‘ako is situated on a portion of the low-lying coastal plain of the Makiki Ahupua‘a in the southeast part of the island of O‘ahu. Makiki Ahupua‘a lacked a perennial stream that could provide an abundant supply of fresh water to the coastal plain, which impacted its settlement pattern. Throughout much of the nineteenth century, the coastal plain of the Makiki Ahupua‘a remained a marshland comprised of “exposed coral flats dotted with salt pans and fish ponds.” By the latter part of the nineteenth century, material from nearby marine-related dredging projects and the ash and ferrous material from the city garbage incinerator was used to fill low-lying portions of Kaka‘ako in response to perceived hazards associated with mosquitos and pond areas as well as the desire to create more land suitable for development. By 1900, government plans had also been drawn up to improve drainage and develop a road system into the Kaka‘ako area (Refer to Figure 2.3).

In 1910, the Territorial Board of Health undertook the Kewalo Reclamation Project in the area bounded by the present-day alignments of Ward Avenue, Ala Moana Boulevard, South Street, and King Street. The low-lying marshlands, tidal flats, fishponds and exposed coral reefs of Kaka‘ako were filled through improvement projects and involved the construction of drainage projects in conjunction with the deposition of fill material.

Spatial Organization and Land Patterns

Throughout the nineteenth century, the low-lying coastal plain of the Makiki Ahupua‘a remained an expansive, undeveloped marshland with scattered dwellings along the coastline and near ponds and trails (Figure 2.5). Its relative isolation and proximity to central Honolulu caused the Kaka‘ako area to become a convenient location for “cemeteries, burial grounds, and for the quarantine of contagious patients.” As land was drained and filled in the first two decades of the twentieth century, the gridded road network was expanded between Queen Street and Ala Moana (compare Figures 2.3 and 2.6). The resulting rectangular blocks were developed with a mixture of public facilities, densely clustered wood- frame dwellings, tenements, and commercial buildings, and large lot industrial uses such as the Honolulu Iron Works.

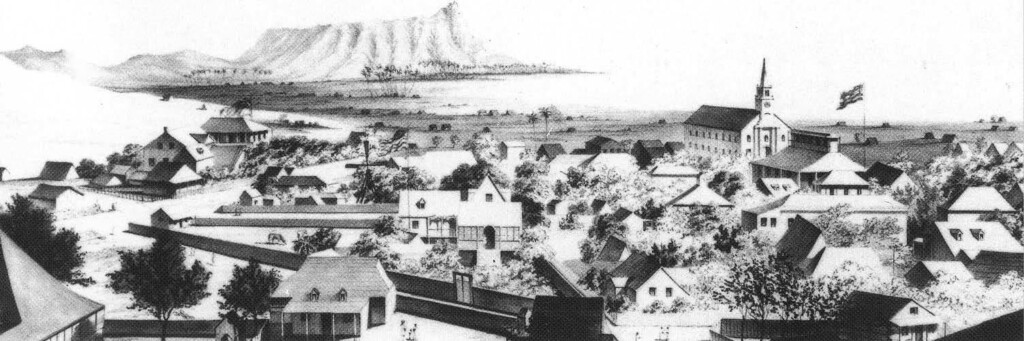

Figure 2.5: 1850 sketch by Paul Emmert depicting the sparsely settled coastal plain between Honolulu and Waikīkī.

(Source: Hawaiian Historical Society; reprinted in Grant et al. 2000:5)

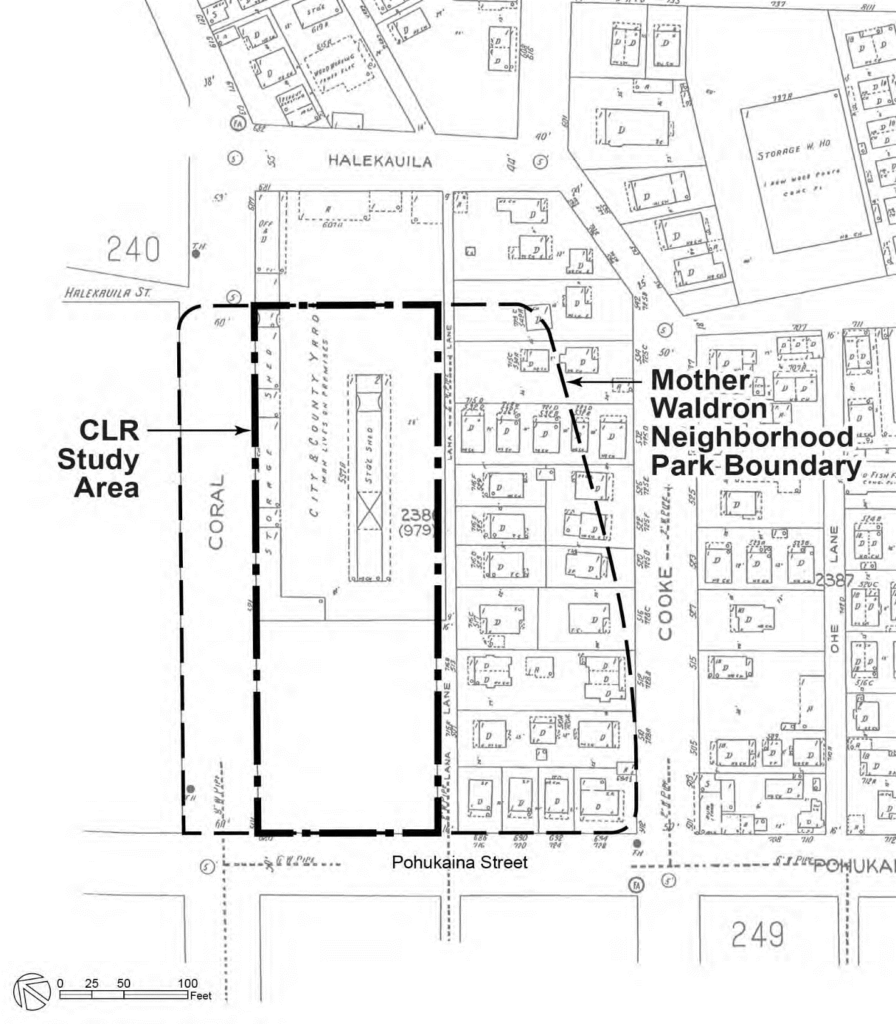

In 1901, the County built government stables on vacant fill land along Coral Street and Second Street (later Pohukaina Street), land that is now a portion of the CLR study area. Ancillary buildings appear to have been located along the edges of the site, enclosing the stable building and yard. By 1913, most of the city block across Coral Street from the stable and defined by Keawe and Second Streets was encumbered by Pohukaina Elementary School and the generous open space around it. The surrounding blocks were densely developed with small residential and commercial structures arranged in linear patterns reflecting the street grid.

- Figure 2.6: Hawaii State Survey Office, Registered Map showing government stables site and Kaka‘ako street system. (Source: portion of “Honolulu, Territory of Hawaii,” Monsarrat, 1920)

- Figure 2.7: CLR Study Area, 1927. (Base Map: 1927 Sandborn map)

Circulation

In pre-contact times, trails through the low-lying coastal plain connected the more populous area of Kou (Honolulu) and Waikīkī. By the late 1800s, the major vehicular corridors between central Honolulu and Waikīkī were King Street, Queen Street and the Beach Road. The Queen Street alignment, which was planned to connect to the beach road near Waikīkī, appears to have followed the route of the traditional trail from Kou (Honolulu) to Waikīkī as described by John Papa ‘Ii in Fragments of Hawaiian History, 1959.

By 1911, Coral Street was the farthest road east of downtown Honolulu that connected the Beach Road with Queen Street until one reached Ward Avenue. Over the next decade, the street grid was expanded across the recently filled lands bounded by Queen Street, Beach Road, Coral Street, Ward Avenue. First and Second Streets (later named Auahi and Pohukaina Streets, respectively) were extended eastward toward Ward Avenue. Cooke, Koula, Mohala and Kamani Streets were added as mauka-makai roads between Halekauwila and First Streets; only Cooke Street continued to the Beach Road, named Ala Moana Road by 1920. The northern edge of the stable site was bordered by a short road segment that dated to 1900, which by the 1920s was considered part of the Halekauwila Street, although it was offset from the new road’s alignment. A narrow drive, Lana Lane, bordered the eastern edge of the stables site, separating it from the adjacent residences.

Views and Vantage Points

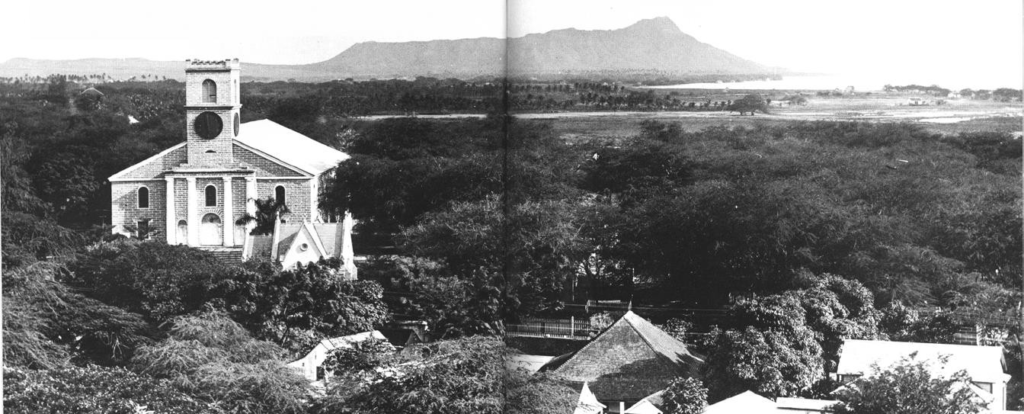

Throughout the nineteenth century, Kaka‘ako’s flat expanse of open and relatively undeveloped marshlands afforded panoramic views in all directions. Key visual landmarks from the district included Punchbowl Crater and the Ko‘olau Mountains to the north, Diamond Head to the east, and the steeple of Kawaiha‘o Church rising above low-rise urban development to the west, and the ocean to the south (Figure 2.9).

Figure 2.9: Circa 1887 photograph looking east across the lowlands of Kaka‘ako and Waikīkī to Diamond Head; Kawaiaha‘o Church in left foreground. (Source: Hawai‘i State Archives, Henry L. Chase Collection; reprinted in Stone 1983:84-85)

2.2 URBANIZATION AND PLAYGROUND DEVELOPMENT (1920 TO 1950)

Kaka‘ako continued to grow and densify as an industrial district. Workers, many of whom were Native Hawaiians, immigrant Asians, Europeans, or Euro-Americans, occupied inexpensive wood-frame dwellings in the surrounding neighborhoods while working at Honolulu Ironworks, the harbor, machine shops, shipbuilding and repair industries, lumberyards, and small neighborhood shops and businesses. By the 1920s and 1930s, the Kaka‘ako district was comprised of a mixture of one-story cottages, two- and three-story tenements, and a number of ethnic “camps” interspersed with commercial, industrial, and public facility buildings.

In response to similar mixed-use and housing conditions in urban areas nationally, influential and well- organized groups of citizens sought to effect social change through the physical transformation of American cities. At the turn of the twentieth century, the national Playground Movement developed in response to public concerns about the physical and social welfare of underprivileged children living in congested urban areas. Reform-minded women were often at the forefront of local efforts that resulted in the creation of hundreds of municipal playgrounds and schoolyards, public athletic fields, and outdoor play spaces for children.

Unlike the scenic open-space parks of the nineteenth century, municipal playgrounds constructed during the 1920s and 1930s were modest in size and designed and operated to provide safe, organized, and supervised recreation for children in urban neighborhoods. Playground supervisors organized and monitored children’s games, sports teams, and other recreational activities. One of their primary tasks was to ensure that each playground was free from bullying, “adult loafers,” and gang activities. Moreover, supervisors acted as role models to help in the socialization and Americanization of immigrant children.

Early efforts at the national level focused on convincing city officials that public recreation was a municipal responsibility. In Honolulu, the privately funded Free Kindergarten and Children’s Aid Association (FKCAA) initiated the development and operation of some of the city’s first playgrounds. The group established playgrounds in Chinatown, at A‘ala Park, Kamamalu, and Atkinson Playground in Kaka‘ako (across Foundry (now Pohukaina) Street from Pohukaina School. In 1922, the Honolulu Parks Commission was established and headed by Julie Judd Swanzy, prominent citizen and president of the FKCAA. Influenced, at least in part, by concerns about the welfare of children from poor or immigrant families, the commission, set about developing and operating new municipal playgrounds. By 1936, the commission supervised some forty playgrounds and social centers throughout Honolulu.

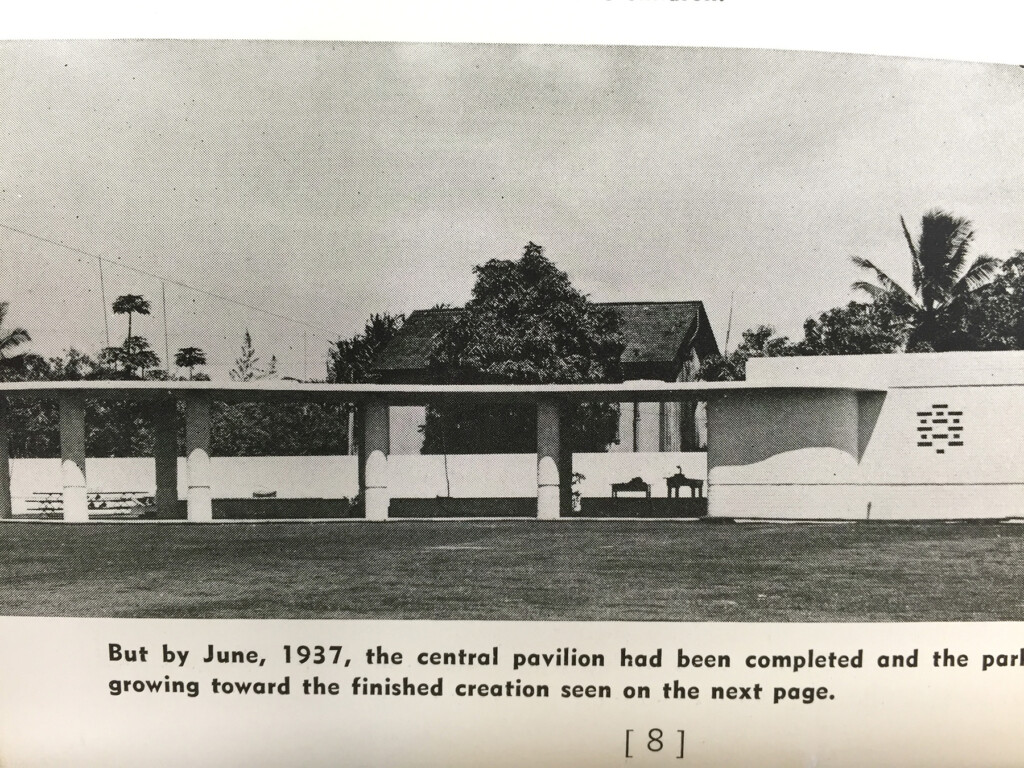

During the 1930s, Honolulu officials utilized federal funds through Roosevelt’s New Deal programs to employ workers in public works projects and to supervise playground activities. Honolulu Park Board chairman Lester McCoy employed architect Harry Sims Bent to design and supervise construction of the city’s public parks. Bent had arrived in Honolulu in the late 1920s to supervise construction of the Academy of Arts for the firm Bertram Goodhue Associates. Following this work, Bent stayed in Hawai‘i, eventually opening his own practice. He worked on nearly all public park projects in Honolulu during the 1930s, including Ala Moana Park (1934), Kawananakoa Playground (1937), Mother Waldron Playground (1937), and others. His work is particularly noteworthy for the creative use of simple materials in creating Art Deco and Art Moderne architectural design elements. Projects constructed during the collaboration between McCoy and Bent are examples of the “golden age” of park building in Honolulu.

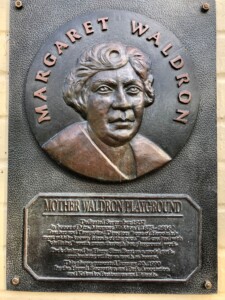

The 1.76-acre site that included the City and County Stables was transferred from the territorial government to the city in 1930 and 1931. Its central location within densely-developed Kaka‘ako and across Coral Street from Pohukaina Elementary School was optimal for a new playground. The site was first proposed to be named for Margaret “Mother” Waldron at this time, but she refused the honor. Several years later, Bent’s plans for this playground were approved by the Park Board in 1936, and Mother Waldron’s name was given to the park following her death that same year. Margaret Waldron began her career teaching fourth grade at Pohukaina School. Outside of education, she was the volunteer playground director at nearby Atkinson Park and a welfare worker in Kaka‘ako. She was credited with nearly single-handedly ridding Kaka‘ako of its gangs and turning their members into model citizens through her organized activities for the district’s youth. In 1937, Mother Waldron Playground was constructed for a total cost of $50,000. The City funded approximately $32,000, while the federal Works Progress Administration funded the balance, including labor. The park opened on September 20, 1937, to much fanfare with city officials and over 2,000 others in attendance, and a performance by the Royal Hawaiian Band. At the time, the playground was heralded as one of the most modern recreational facilities in Honolulu.

The 1.76-acre site that included the City and County Stables was transferred from the territorial government to the city in 1930 and 1931. Its central location within densely-developed Kaka‘ako and across Coral Street from Pohukaina Elementary School was optimal for a new playground. The site was first proposed to be named for Margaret “Mother” Waldron at this time, but she refused the honor. Several years later, Bent’s plans for this playground were approved by the Park Board in 1936, and Mother Waldron’s name was given to the park following her death that same year. Margaret Waldron began her career teaching fourth grade at Pohukaina School. Outside of education, she was the volunteer playground director at nearby Atkinson Park and a welfare worker in Kaka‘ako. She was credited with nearly single-handedly ridding Kaka‘ako of its gangs and turning their members into model citizens through her organized activities for the district’s youth. In 1937, Mother Waldron Playground was constructed for a total cost of $50,000. The City funded approximately $32,000, while the federal Works Progress Administration funded the balance, including labor. The park opened on September 20, 1937, to much fanfare with city officials and over 2,000 others in attendance, and a performance by the Royal Hawaiian Band. At the time, the playground was heralded as one of the most modern recreational facilities in Honolulu.

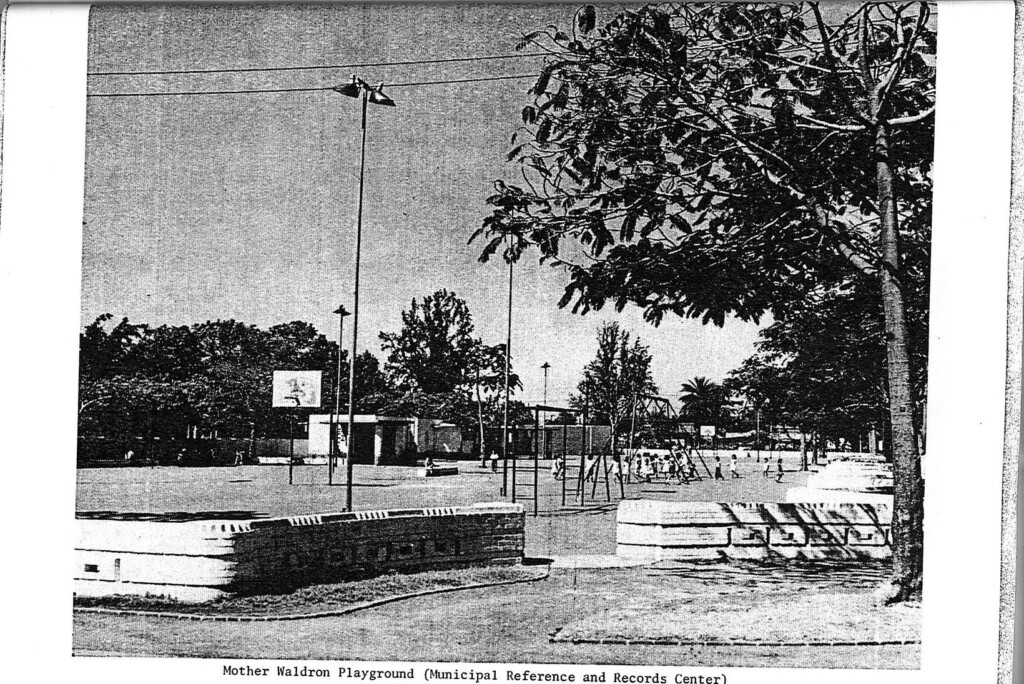

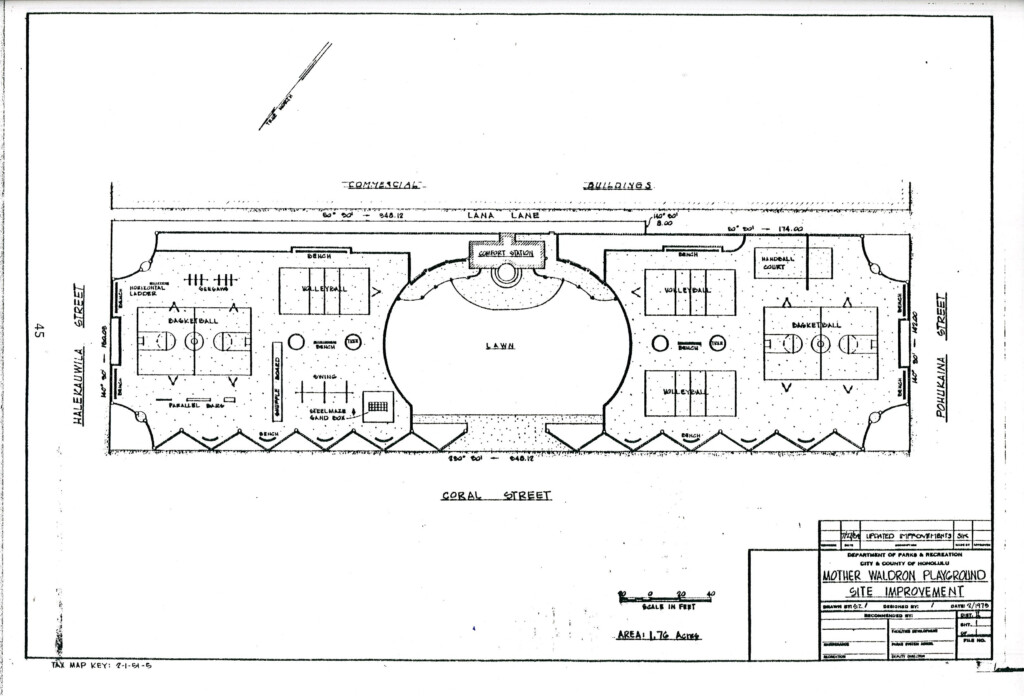

Bent’s symmetrical plan featured a central comfort station with curved pergolas, a broad open lawn, and numerous play courts. The comfort station and lawn separated the junior and senior children’s play areas that contained volleyball and basketball courts. The senior playground also had handball courts, while the junior playground had playground equipment.

Bent delineated the playground from the surrounding streets with 3-foot-high, zigzag-shaped walls. The design of the walls featured courses of concrete brick with horizontal and vertical perforated openings and a decorative horizontal band. Each corner of the park contained a curved entry wall with rounded piers at the pedestrian openings. The landscape design was symmetrical as well as aesthetic and functional.

Upon completion, children and adults in the community used the playground on a regular basis. Students at Pohukaina Elementary School played there during recess and lunch breaks. Adults used the play courts for nighttime recreation and social activities such as bon dances, music and dance performances, and even political rallies. Street parking around the perimeter of the park provided easy access for residents as well as visitors. In 1941, 60,000 persons were reported as having used the park during the daytime and another 26,000 used the site for evening sports and social gatherings.

In the 1940s, Honolulu, like many cites in the United States, reorganized playground administration and operations under municipal parks and recreation departments. The Honolulu Park Board merged with the Recreation Commission to form the Board of Public Parks and Recreation. After World War II, the board focused on restoring and rehabilitating municipal parks that had been used, and in some cases damaged, by the military during wartime defense operations. By the end of the 1940s, the focus of playground planning efforts had changed in favor of providing play equipment that promoted children’s free play and imagination rather than the structured and supervised playground environments developed during the two previous decades.

As Honolulu continued to grow, land near the urban core became increasingly valuable. In Kaka‘ako, residential lots were consolidated and redeveloped with warehouses and light industrial uses while many residents moved to suburban communities. In some cases, the low-cost housing of an earlier era was determined “dangerous and unfit for human habitation” resulting in families being subjected to evictions to facilitate the demolition of housing and expansion of warehouses and other facilities.

By 1950, lot consolidation and redevelopment had begun to change the historic development patterns and spatial organization of the Kaka‘ako district. The residential lots between Mother Waldron Playground and Cooke Street remained virtually unchanged, however, even though residential lots makai of Pohukaina Street were cleared, consolidated, and redeveloped as warehouses. Fire insurance maps indicate that in the surrounding community, a number of small land parcels were consolidated and redeveloped, while some single-family dwellings were converted into duplexes.

Figure 2.14: Photo of the junior playground from the main entrance of Mother Waldron Playground along Coral Street, ca. 1938. Young tree plantings are protected within the lattice cages. The Ko‘olau Mountains are prominent in the background. (Source: Honolulu Park Board, Your Parks: Annual Report for 1938)

2.3 PLAYGROUND RENOVATIONS AND URBAN REDEVELOPMENT (1950-2015)

HISTORICAL CONTEXT

In the second half of the twentieth century, Honolulu’s urban core, like those of many cities throughout the country, experienced a decline in population levels and a decrease in the level of private economic reinvestment. Federal funding in the form of credit and home loan assistance for military veterans in concert with government investment in major transportation and infrastructure projects helped to promote growth and development in outlying suburban districts. Public concerns about blight and urban decay prompted the Territorial Legislature to create the Honolulu Redevelopment Agency (HRA) to focus on urban renewal. Early efforts by HRA focused on clearing dilapidated structures and urban blight in Kalihi, central parts of the city closest to the west side of downtown, and the Kapahulu areas. As the aging building and housing stock of earlier eras deteriorated, a number of residents either voluntarily moved or were required to relocate to other areas to facilitate new commercial development in Kaka‘ako.

Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, many Honolulu residents migrated from the older, ethnically distinct residential districts in favor of subdivisions in outlying areas that tended to be homogenous in terms of age and income rather than race. Neighborhood stores and shops once scattered throughout the city and operated by immigrant families gradually started to disappear due, at least in part, to the combined effects of young educated family members entering into higher-paying occupations and the increased use of the automobile to meet family shopping needs. By the 1960s, the urban core of Honolulu had taken on a “positively lonely appearance after dark and on holidays.” The population decline in Kaka‘ako resulted in the few remaining students leaving Pohukaina Elementary School after 1966 for Royal and Lincoln Elementary Schools. The Pohukaina building then became a special education facility. In 1967, the Honolulu City Council considered a proposal to replace Mother Waldron Playground with a city parking garage. At the time, proponents cited the widespread belief that Kaka‘ako was an industrial area without permanent residents.

In an effort to reverse the general state of decline in older urban neighborhoods, both the State of Hawai‘i and the City and County of Honolulu focused on stimulating redevelopment and economic reinvestment activities. Legislators believed that certain underused and deteriorating areas had the potential to improve investment opportunities and provide economic benefits to the citizens of Hawai‘i once redeveloped. In 1976, the Hawai‘i State Legislature created the Hawai‘i Community Development Authority (HCDA). HCDA was tasked with supplementing ongoing redevelopment efforts by promoting and coordinating public and private sector development in designated Community Development Districts. Kaka‘ako was designated as the Authority’s first Community Development District and the Authority undertook plans to revitalize the area into a vibrant, mixed-use district of housing, parks, and commercial and industrial uses.

Figure 2.18: This Dept. of Parks and Recreation sketch of Mother Waldron Playground reflects conditions in 1975. (Source: Weyeneth and Yoklavich, 1987, p 45; at MRRC)

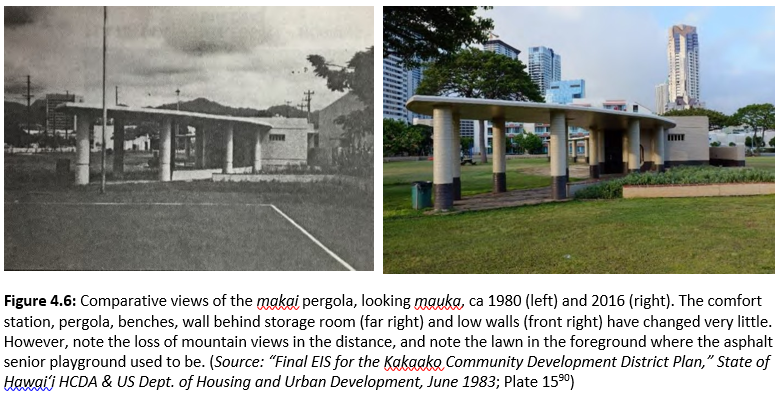

From the time of its initial construction and through the 1980s, Mother Waldron Playground underwent periodic maintenance and renovation with limited effect on the original land area and design of the playground. Records on file with the City indicate that plans were approved in 1967 to add a linear strip of asphalt pavement inside the main entrance to the playground. At some time prior to 1969, a wide, curved swath of flagstone pavement was installed in front of the comfort station to connect the pergola walkways. In 1969, plans were prepared by the City Department of Parks and Recreation to renovate the comfort station, replace damaged or missing tile caps on various benches and walls, repair flagstone pavement near the comfort station, replace missing trees, and add or adjust play apparatuses on the junior side of the playground. Sprinklers were designed for the planting space along the Lana Lane wall about 1972, and the play courts were resurfaced in 1978 (Figure 2.18). Although the full extent to which planned renovations and improvements were implemented is uncertain, documents from later decades indicate that changes to the original design of the park were generally minor through the 1980s.

As Kaka‘ako became more industrial in nature, and the Pohukaina School building continued to deteriorate, the school’s program (serving just 95 special education students in 1979) was transferred to Kaimuki Intermediate’s campus in 1981, and the Pohukaina School buildings were demolished.

One of the major factors that hindered redevelopment in the Kaka‘ako district was an aging infrastructure system. In the 1980s, HCDA began plans to support revitalization of Kaka‘ako, including road reconfigurations to improve vehicular circulation. In the early 1990s, Pohukaina Street was widened and related infrastructure improvements installed. The expanded right-of-way encroached slightly into the older children’s playground but did not affect recreation features. The Pohukaina perimeter wall and benches were removed and reconstructed approximately 5-10 feet mauka of their original locations. Trees and vegetation were removed and replaced, and a new gutter, concrete curb, and sidewalk were installed.

Between 1991–93, Halekauwila Street was realigned and widened (Figure 2.19). The project entailed the removal and reconstruction of the playground’s Halekauwila Street perimeter wall, Halekauwila/Coral Street pedestrian entryway, and relocation of two benches to approximately 90 feet makai of their original site. The pedestrian entryway near Lana Lane was eliminated because the reconstructed Halekauwila wall was extended to join the Lana Lane perimeter wall. The basketball court was also eliminated due to the road realignment. A new sidewalk, concrete curb, gutter, box drains, street lights, and planting areas were installed. In total, approximately 12,700 square feet of the playground was lost to the street realignment.

Figure 2.19: Aerial photograph from 2000 depicts the Mother Waldron Neighborhood Park following realignment of Halekauwila Street and the incorporation of Coral Street right-of-way and land area to Cooke Street as part of the park. It also shows redevelopment of the former school site and lands mauka of Halekauwila Street. (Source: http://magis.manoa.hawaii.edu/remotes ensing/GeoserverFiles/ShpFiles/Oahu/018

/jpegs/930)

Following the realignment of Halekauwila Street, the City created Mother Waldron Neighborhood Park by incorporating land in the ‘Ewa and Diamond Head directions of the original playground. As part of the HCDA Kaka‘ako Improvement District Project (1994 Cooke Street Expansion Project), the Lana Lane right-of-way and the vacant parcel between the lane and Cooke Street were added to the playground. The warehouses and other buildings formerly located on this parcel had been razed before the project was initiated. Also as a part of this project, the Lana Lane perimeter wall and the handball court wall were removed.

In conjunction with the Halekauwila Street widening project and other nearby development projects, a number of human remains dating from the late pre-historic or early historic periods were uncovered. Cooperation between HCDA, the State Historic Preservation Division, the O‘ahu Burial Council, and other interested parties resulted in the installation of a re-interment vault near the intersection of Halekauwila and Cooke Streets. The vault, designed in 1994 as part of the Cooke Street expansion, mark the final resting place of Native Hawaiian iwi kūpuna (human bones) that were uncovered.

In 1994–95, the Coral Street right-of way between Halekauwila and Pohukaina Streets was closed and approximately 25,800 square feet was added to the park. A grove of kou trees was planted at each end of the right-of-way and grass replaced the street pavement, except for a relatively small rectangular portion near the Coral Street entrance to the original playground.

The 1994 Cooke Street Expansion Project drawings still referred to the 1937 1.7-acre playground site and the land between the playground and Cooke Street as Mother Waldron Playground. However, the 1994, City Dept. of Parks and Recreation project for the “Demolition, Irrigation & Grassing” of Coral Street was called “Mother Waldron Park Expansion.” Various City drawings for site improvements between 1995 and the 2004 consistently refer to the 3.4-acre CLR study area as “Mother Waldron Neighborhood Park” rather than “playground.”

In late 2013, the City and County prepared plans for several site improvements, which were likely implemented in 2014. Missing trees within the wall alcoves were replaced and groundcovers planted. Most notable was the removal of historical recreational pavement and the addition of lawn in its place.

- Figure 2.20: View across the junior playground from Halekauwila Street near Coral Street. Note the large royal poinciana tree in the entry planting island at right and canopies of the mature trees along Coral Street beyond it. Royal Poinciana trees along the Lana Lane wall are visible at left. (Source: Weyeneth & Yoklavich, 1987, from Municipal Reference and Records Center)

- The perimeter wall in 2016.

- Comparative views of the comfort station and mauka pergola in 1937 (left) and 2016 (right).

- Note the modified block openings in the restroom wall and the two-color paint scheme.

Historic Hawai‘i Foundation’s Preservation Programmatic Award recognizes excellence in advocacy, educational, programmatic, or other activities that promote site-specific or broad-based preservation efforts. The 2021 Preservation Honor Awards Virtual Ceremony was held on Friday, May 21st. Click here to watch the recording.