Beatrice K.H. Krauss, PhD

Ethnobotanist, Teacher, Activist and much more…

(August 4, 1903 – March 5, 1998)

By HHF volunteer Rona Holub

Beatrice Krauss was born in Honolulu on August 4, 1903 on the grounds of the original Kamehameha School in Kapālama (while her father was a teacher there). Her parents, transplants to Hawai‘i from San Francisco, later settled in Mānoa. Krauss graduated from Punahou School, received her graduate degree at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa, and later studied at the University of Berlin and Cornell University. She spent a large part of her career in research at the Pineapple Research Institute for over forty years, then became an educator.

Her interest in the care of the land and most particularly in plants, was influenced by her father, Frederick Krauss, a professor of agriculture at the University (after whom Krauss Hall is named). Beatrice Krauss attended the University majoring in agriculture and became the first woman to attain a degree in that discipline. Records show that at her research job at the Pineapple Research Institute, she served as an assistant physiologist in the 1930s and was part of an unusually diverse team of professionals for the time, housed in buildings adjacent to the UH campus. Throughout her career at the Institute, she worked as a plant physiologist and morphologist. As such, she would have conducted research in the physiology, breeding, and yield of pineapple crops with expert knowledge of the physiology, anatomy and form of plants.

At UH, Beatrice Krauss taught ethnobotany, the study of native people and their plants. Her class became one of the most popular, so much so that it grew from one section to six. She received no salary for teaching, however, because she refused to sign the compulsory loyalty oath, a requirement that had been instituted for the second time in 1941, at the start of World War II when the loyalty of Hawai’i residents of Japanese ancestry was questioned.

The first loyalty oath, concerning the loyalty of German Americans, was enforced during World War I and a period of widespread anti-German sentiment. The Krauss family, who spoke German at home, lived on Maui at this time. Beatrice’s father was required to travel back and forth to Honolulu to assert that they were not German spies and proclaim his loyalty to the United States. Not surprisingly, they flew the Stars and Stripes over their home at all times. This experience clearly influenced Beatrice Krauss’s later staunch opposition to government coercion.

Krauss, a woman of strong principle and social justice, opposed such measures for anyone. In 1948, amidst a looming tension of post-war anti-communism, Krauss was one of four people who testified in defense of John Reinecke, a labor leader and teacher, accused of being a communist. The school where he taught sought to ouster and revoke the teaching licenses of both he and his wife, Aiko. Krauss stated that even if they were Communists, their beliefs had nothing to do with their abilities as teachers. When asked if she had ever asked the Reineckes if they were communists, she retorted, “Why should I?”.

In 1953, Reinecke and six others, including labor leader Jack Wayne Hall, also known as the Hawai‘i 7, were convicted under the Smith Act which made it a criminal offense to advocate the violent overthrow of the government or belong to a group that advocated the same. They were each sentenced to 5 years in prison and a $5,000 fine; after an appeal, however, a district court overturned the conviction. Beatrice Krauss opposed and protested the entire proceeding.

Beatrice Krauss was truly her own person–unconventional, independent, adventurous and bold. It seemed that very little phased her. She traveled abroad for a year, including a stint in the Canary Islands studying pineapple culture and wound up stranded in the Azores for two and a half months as steamships stopped their regular runs at the outbreak of World War II in Europe. She returned to Honolulu in 1939 aboard the Lurline.

While Krauss taught at the University, she would tell her stunned (and presumably grateful) students that she gave no exams and gave everyone an A or B. “This is my way of thumbing my nose at the grading system,” she remarked. Krauss noted that the administration never bothered her about any of it, calling her a “character” and accepting her way of doing things. Perhaps the fact that her class enrollment shot up from 50 to 550 played in her favor!

In 1973 Krauss led a group that tried to save Gilmore Hall and neighboring trees on the UH campus from demolition. Though she helped place the building on the Hawai‘i Register of Historic Places, the Hall was torn down to make way for a new art building. A balbao tree was saved after Krauss reportedly chained herself to it in protest.

In 1974, in response to an invitation from Dr. Yoneo Sagawa, director of the Lyon Arboretum from 1976-1991, Krauss became a full-time volunteer there. Together they formed the Lyon Aboretum Association as a support group which allowed them to offer classes to the public. For twenty years, she helped develop classes on plant propagation, plant care, cooking, and even tours of Chinatown. To honor her in 1987, the Aboretum established the Beatrice H. Krauss Hawaiian Ethnobotanical Garden which houses the largest collection of Hawaiian cultural plants on O’ahu.

A life-long resident of the Mānoa Valley, Krauss initiated the Mānoa History Project which led to the development of the book, Mānoa, The Story of a Valley, a rich collection of primary source material from long-time residents of the valley.

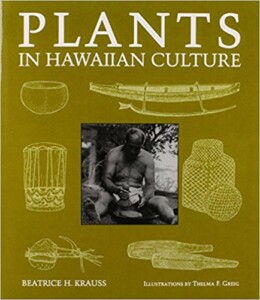

Beatrice Krauss dedicated her life to the study and sharing of knowledge about plant life in Hawai‘i and the significant and important ways in which native Hawaiians used plants in everyday life. She is remembered for her deep respect for the native culture and for her generosity as a lifelong educator and active community member.

Her significant work on plants in the Hawaiian Islands includes Plants in Hawaiian Culture, Ethnobotany of the Hawaiians, and Plants in Hawaiian Medicine.

Her significant work on plants in the Hawaiian Islands includes Plants in Hawaiian Culture, Ethnobotany of the Hawaiians, and Plants in Hawaiian Medicine.

Mahalo to Lila Gardner who did the oral histories of Beatrice Krauss for Malama Mānoa and provided support for this article.

Resources for further reading:

http://malamaomanoa.org/wp-content/uploads/Krauss-Beatrixe-Vol.-1-.pdf

https://www.blueplanetjourney.com/2018/02/beatrice-kapuaokalani-hilmer-krauss.html

Oral History Video of Beatrice Krauss:

http://uluulu.hawaii.edu/titles/12356

Photos of Beatrice courtesy of Blueplanetjourney.com.