Article Written By: Katrina Valcourt

What is it?

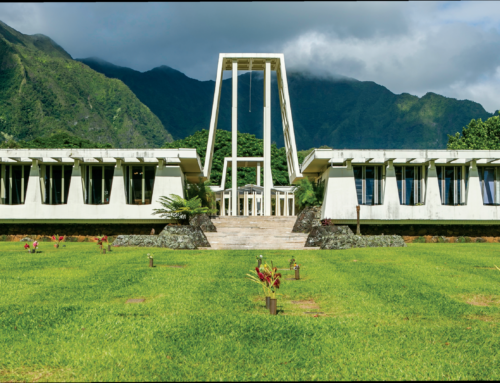

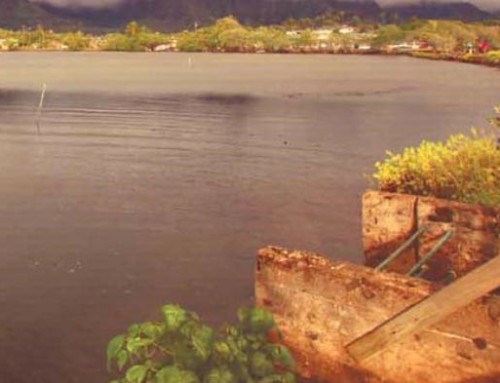

Kamehameha III’s summer home, Kaniakapupu, built in the 1840s, is one of the last sites associated with Kauikeaouli and may be where part of the Great Mahele was written. That’s according to Baron Ching, vice chair for Ahahui Malama o Kaniakapupu. It also served as a chief’s children’s school. “Every single high-ruling king or queen was within the walls of Kaniakapupu,” Ching says. A plaque at the site declares there was once a luau held there in honor of Hawaiian Restoration Day, with 10,000 people in attendance, but not much is known about its use after 1847.

Though many people hike to the ruins, the area is part of a restricted watershed and is off-limits to the public.

What threatens it?

Erosion remains a constant treat. In June, someone etched crosses into three of the walls, damaging the stone blocks and the integrity of the structure, as well as desecrating this important cultural site. (This is not the first time it’s been vandalized, either.) Since then, others have attempted to scratch the crosses off, further degrading the 180-year-old palace. Google and Instagram searches reveal photos of people doing photo shoots, leaning on walls, and even climbing and sitting above the doorway.

The Department of Land and Natural Resources has asked more than a dozen blogs to remove information and directions leading people to this restricted area, but social media make it accessible despite DLNR efforts.

What can be done?

“Over the years, we’ve discussed a lot of things,” Ching says, including putting up a fence encircling the ruins, putting up more signs explaining their cultural significance and installing video cameras in the parking area. “Ultimately what needs to happen is we need the state to send somebody up there, like a ranger or somebody, to actually watch the place during daytime hours…something that DLNR doesn’t have money for.” The Ahuhui comprises about half a dozen regular volunteers, but “we all gotta pay our rent,” Ching says; they can’t afford to be up there 24/7. They’re hopeful that more education about why the place is significant and possible interns form other organizations can help protect it since, once it’s damages, it cannot be repaired.

DLNR’s senior communications manager, Dan Dennison, says, “Certainly fencing and signage are two of the options under consideration.”

- Photos Courtesy of DLNR