1877: King David Kalakaua designates Crown land at the foot of Diamond Head to be “a place of innocent refreshment for all who wish to leave the dust of the town street.” This area now includes Kapiolani Park, the Waikiki Zoo, the Waikiki War Memorial Natatorium and the Waikiki Aquarium.

1877: King David Kalakaua designates Crown land at the foot of Diamond Head to be “a place of innocent refreshment for all who wish to leave the dust of the town street.” This area now includes Kapiolani Park, the Waikiki Zoo, the Waikiki War Memorial Natatorium and the Waikiki Aquarium.

1896: After the the overthrow of the Hawaiian Monarchy, trustees of the Kapiolani Park Association deeded the major portion of the park to the Republic. Parcels were then carved out as fee simple land, including a parcel to Kapiolani Park Trustee, W.G. Irwin.

1914: World War I begins.

1919: World War I ends with the signing of the treaty of Versailles.

1919: The Territorial Legislature under Governor McCarthy appropriates $200,000 to purchase 6.4 acres of the W. G. Irwin land makai (seaward) of the Kapiolani Park boundary through Act 191 (P. 257 – S.L. 1919) specifying that the land should be designated as the “Memorial Park.”

May 17, 1920: Governor C. J. McCarthy’s Executive Order No. 73 set aside the 6.4 acre site for park purposes, “The same to be cared for managed and controlled by the city and county of Honolulu, until the Legislature shall otherwise provide.”

1921: The Hawai‘i Chapter of the American Legion forwards a request to the Hawai‘i Territorial Legislature to build a memorial to the men and women who served in World War I.

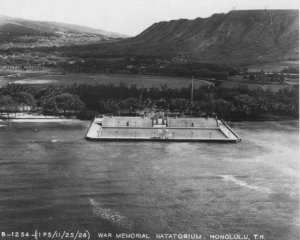

1921: Act 15 (P.21- S.L. 1921) appropriated $250,000.00 “to provide a memorial to the men and women of Hawai‘i who served during the Great War.” A bond issue authorized in the amount to be payable by the three counties and the City. This act also authorized the Governor to appoint a “Territorial War Memorial Commission of three members to conduct an architectural competition for the design of the memorial. The plans shall include a swimming course at least 100 meters in length.” $10,000 was appropriated from the general fund for the expenses, including the awarding of prizes by the commission. Mr. Lewis P. Hobart, Architect, won the design competition.

1923: Act 14 (P. 11 – S.L. 1923) amended Section 4 Act 15 to allow counties to raise tax rate to repay bonds.

1925: Act 111 (P. 129- S.L. 1925) amended Act 15 directing that the Natatorium to be built within appropriation.

1927: The Natatorium, constructed by Mr. T. L. Cliff, was completed. See the original architectural plans (large PDF).

August 24, 1927: Natatorium officially opens on the birthday of Duke Kahanamoku, who dives in as the inaugural swimmer to a roaring of applause from the large audience.

June 7, 1929: Honolulu Star-Bulletin article “When Will Something be Done?” describing the deplorable conditions of the Natatorium and grounds under the supervision of the City and County of Honolulu.

June 17, 1929: Governor Farrington’s Executive Order 359 cancels Governor McCarthy’s Executive Order No. 73 (1920) which gave the City and County of Honolulu management and control of the Natatorium site.

Governor Farrington issues Executive Order 360 transfer the maintenance of the Natatorium to site to the Territory of Hawai‘i under the Department of Public Works.

Act 255 (S.L. 1929) provides for the transfer and maintenance of the Natatorium site to the Territory of Hawaii Department of Public Works

1929: Contract awarded to T.L. Cliff to dredge and enlarge deep section of pool.

1941–1943: U.S. Army uses the Natatorium for training.

1949: United Construction Company repairs and refurbishes the Natatorium for $81,886.

Returning the Management Back to the City and County of Honolulu

July 1, 1949: Act 6 (S.B. 66 – S.L. 1949) transfers the management and appropriations for the Waikiki War Memorial Natatorium to the City and County of Honolulu Board of Parks and Recreation.

June 14, 1951: Governor Long’s Executive Order No. 1445 cancels Governor Farrington’s 1929 Executive Order No. 360 and Executive Order No. 1446 transfers the management and operation of the Natatorium back to the City and County of Honolulu pursuant to Act 6 (S.B. 66 – S.L. 1949).

November 25, 1952: Governor Long’s Executive Order No. 1536 withdraws 2.3 acres from the Natatorium Memorial Park land to be used for U.H. Waikīkī Aquarium site.

1959: Hawaii becomes the 50th State.

April 23, 1963: Natatorium was closed due to poor water quality (Source: Honolulu Advertiser, May 7, 1963).

September 9, 1963: City and County Building Department reports on the hazardous conditions of the structure.

April 15, 1965: Donald Wolbrink & Associates, Inc. releases study of the hazardous conditions of the Natatorium.

June 8, 1965: Honolulu City County votes to demolish the Natatorium upon the recommendation by Mayor Neal S. Blaisdell.

1965: U.S. River and Harbor Act of 1965 authorizes Beach Erosion Control Improvements for Waikīkī Beach with plans to developed jointly by Department of Transportation, the City and County of Honolulu and U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.

1966: U.S. Congress passes the Historic Preservation Act

1972: U.S. Congress authorizes $1.3 million for Beach Erosion Control Project appropriation to be used for demolition of Natatorium and beach restoration including required groins from Sans Souci Beach to Queen’s Surf per plans developed by U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and the State Department of Transportation. Read the Draft Environmental Impact Study (1972).

February 5, 1973: The Waikīkī War Memorial Natatorium placed on the Hawai‘i Register of Historic Places.

1973: Land Board approves and recommends cancellation of Executive Order No. 1446 to allow demolition of the Natatorium.

October 1973: The Natatorium Preservation Committee filed suit in the First Circuit Court against the US. Army Corps of Engineers and the State to stop them from demolishing the Natatorium. The trial court ruled against the Natatorium Preservation Committee, but, upon appeal, the State Supreme Court ruled in favor of the Preservation Committee and reversed the Trial Court’s decision.

In response to the Hawai‘i Supreme Court’s ruling, the Land Board abandons action to cancel Executive Order No. 1446, which would have allowed for demolition of the Natatorium.

1975: Senate Bill No. 384 appropriates $500,000 to be spent by the City for the restoration of the Waikīkī War Memorial Natatorium. The Appropriation requires matching funds by the City.

1977: Act 9 passes in special session of the Hawai‘i State Legislature, appropriates $500,000 for planning of the demolition of the Natatorium.

April 25, 1979: City and County of Honolulu City Council passes City Council Resolution No 79-89 which returns the management of the Memorial Natatorium to the State of Hawai‘i, petitions the State to cancel Executive Order No. 1446 and leaves the State of Hawai‘i to determine the use and disposition of the Natatorium.

June 1979: Natatorium officially closed.

May 23, 1980: Waikīkī Memorial Natatorium placed on the National Register of Historic Places.

December 1980: Waikīkī Memorial Natatorium padlocked. The Waikiki Task Force, assembled by the Honolulu City Council, recommends the demolition of the Waikiki War Memorial Natatorium to the State Land Board.

April 1981: State Senate Resolution #209 requests DLNR report on the disposition of the Natatorium.

December 1981: Hawaii State Department of Land and Natural Resource releases study of options and recommends that the Natatorium be restored for recreation-commercial use.” Read this report.

1982: City and County of Honolulu releases Kapiolani Park Master Planning Report suggesting the Natatorium Memorial become a passive park.

1982: Hawaii State House Concurrent Resolution No. 173 resolved that the Natatorium structure “must be demolished” and that “a study is needed to analyze design options” of:

1. Complete Beach restoration following the demolition.

2. Conversion from Natatorium to landscaped peninsula.

3. Conversion of all or part of the makai walls to act as a groin for beach areas.

Editor’s Note: HCR 173 is based largely on an “ad hoc” committee’s findings. The resolution, the resulting study and the subsequent plans include no records of the information for which the committee’s conclusions were based, nor a listing of the members of this committee nor their qualifications. This is particularly important because this resolution opposes the conclusions of Department of Land and Natural’s Resources report.

$500,000 for planning and engineering were included in 1982 budget.

February 1983: DLNR reported on the costs of demolition scenarios requested in the HCR No. 173 which stated that the Natatorium structure “must be demolished.” No appropriations were made for this study, and the study notes that it was therefore based on past studies.

1983: Kapiolani Park Master Plan defines the City and County of Honolulu’s policy to create passive use of the Natatorium area.

1984: Governor Ariyoshi releases $100,000 for a planning and feasibility study of the Natatorium. The City and County of Honolulu uses these appropriated funds to contract CJS Group Architects to prepare a planning report for the Natatorium as a passive park area.

March 23, 1984: Board of Land recommends Governor Ariyoshi issue an executive order to cancel Executive Order 1446 and set aside the land for a “Memorial Park.”

May 1984: CJS Group-Architects, Ltd. contracted by the City and County of Honolulu using State appropriated funds, releases preliminary planning report to demolish the Natatorium and use the site as a passive park area.

July 11, 1984: Governor Ariyoshi issues Executive Order 3254 canceling Executive Order No. 1446. (Subject to disapproval by the state Legislature by two-thirds vote of either House or Senate or by majority of both.)

1984: Governor Ariyoshi issues Executive Order No. 3261 setting aside “Memorial Park” to be under the control of the City and County.

November 1984: City and County consultants presents alternative schemes for the Natatorium site, finalized report released in 1985.

1986: State Legislature appropriates $1.2 million for planning and design for the renovation of the Natatorium.

January 1987: Governor John Waihee released funds for planning and design. Leo A. Daly contracted to prepare planning and engineering report on all alternatives including demolition, partial and complete restoration.

1990: Per the findings of the Leo A Daly report and site-specific ocean engineering surveys, the State and the City and County determine that complete restoration should be pursued. City Council passes Ordinance 90-1 (over the Mayor’s veto) mandating the Department of Parks and Recreation Operate and maintain the Waikiki War Memorial Natatorium, including structure, facilities and grounds. Operating and maintenance funds appropriated.

1992: Dept. of Land and Natural Resources Contracts and Leo A. Daly, Alfred A. Yee Division, to draw final plans and specifications for full restoration of the Natatorium as close to its 1927 appearance as possible and to work closely with the City’s Park and Recreation department which would be maintaining the Natatorium after restoration.

1993: Inadvertent discovery of burials at the Waikiki Aquarium, the land adjacent to the War Memorial Natatorium and part of the parcel of land acquired for Memorial Park.

March 23, 1993: Environmental Impact Statement Preparation Notice for the Waikiki War Memorial and Natatorium Restorations published in the Office of Environmental Quality Control (OEQC) Bulletin. Review and comment period extended to May 6, 1993 at the request of the State of Health. Waikiki Aquarium submitted the only comment.

October 23, 1993: Draft Environmental Impact Statement for the Waikiki War Memorial and Natatorium Restoration published in the Office of Environmental Quality Control (OEQC) Bulletin with a review and comment period ending December 1993. (Comments were accepted after due date and all of the numerous comments received responses.)

Editor’s Note: The Waikīkī War Memorial Natatorium’s original design was never fully implemented during construction due to budget cuts. The resulting drainage system in the Natatorium was a constant problem resulting in poor water circulation and poor water quality. The restoration plans included vast improvements to the water circulation allowing the water quality to be that of the surrounding ocean.

1994: State Legislature appropriates $300,000 for additional planning, design and construction.

1995: The National Trust for Historic Preservation names the Waikiki War Memorial Natatorium as one of the 11 Most Endangered Historic Sites in the United States.

1998: The 1995 EIS is accepted, all permits are in place, and full funding ($11.5M) is provided by the City and County of Honolulu for complete restoration for the Natatorium.

January 5, 1999: Plaintiffs for a group identifying themselves as the “Kaimana Beach Coalition” (represented by Attorney James Bickerton), Richard Bernstein and Maile Yawata file suit against the City and County of Honolulu and the Department of Health so that the court would declare that the Natatorium to be classified as a “public swimming pool,” and to stop the City and County from developing or operating a swimming pool without a permit from the State Department of Health.

1999: Judge Gail Nakatani ruled that the pool would need a health department permit as if it were a fully enclosed fresh water pool. City attorneys said the judge’s ruling disregarded the legislative history and intent of the rules as well as state Health Director Bruce Anderson’s admission that the rules were never intended to apply to salt water.

The court decision granted the “Kaimana Beach Coalition’s” request, and a restraining order was issued to the City to halt all restoration until a State Health Permit was issued.

Note: Now that an additional permit would be required, the Shoreline Management Zone Permit, issued in 1998, was arguably no longer valid because it required all applicable permits to be obtained. To make matters worse, getting the permit from the State Health Department was not possible at the time because, as the Health Department pointed out in testimony, the rules for pool permits were not written for saltwater. So, before a permit could be granted, the State Health Department had to first develop, then implement new rules for salt water in pools.

August 4, 1999: Circuit Judge Gary Won Bae Chang lifted the temporary restraining order against the city and ruled that the city has received all the necessary permits so far for the land based portions of the restoration. The work on the pool section remained halted until the State Health Department permit was approved.

May 29, 2000: The restoration of Phase I complete.

January 29, 2001: The State Department of Health holds a public hearing regarding its draft of rules for salt water pools. At the hearing Attorney James Bickerton, an attorney for a group identified as “The Kaimana Beach Coalition,” criticized the rules for not being stringent enough and should include testing for staph infections. (The State Health Department explained that there are no standards for testing for staph infections) Rick Bernstein, President of the Kaimana Beach Coalition, requested that fecal bacteria be monitored more frequently than the proposed requirement of weekly testing.

July 15, 2002: Final State Department of Health rules for obtaining permits for saltwater pools go into effect.

May 2004: Pool deck collapses. Because the structure is built as one piece, the structural issue on the pool affected the structural safety of the restrooms. City forced to close restrooms.

2004: City & County of Honolulu contracts Wilson Okamoto Corporation to prepare a condition report for the Natatorium.

September 23, 2004: City proceeds with $6 million emergency repair of the pool walls.

October 14, 2004: Waikīkī Aquarium proposes Natatorium Site for Aquarium feature.

November 24, 2004: Attorney James Bickerton, representing a group identified as the “Kaimana Beach Coalition” files suit against the city requesting that work to the pool halt until all permits are reissued. Bickerton argued that the work to be performed is substantially different then the plans submitted to receive the original permits.

January 2, 2005: Mufi Hannemann takes office as the Mayor of the City and Council of Honolulu. He vows to fulfill his campaign promise to stop spending on the repair or restoration of the Waikīkī War Memorial.

January 3, 2005: Mayor Mufi Hannemann stops all work on the repair of the Waikiki War Memorial Natatorium.

July 2005: The Waikīkī Natatorium is listed in the inaugural list of Hawaii’s “9 Most Endangered Historic Sites” published by Honolulu Magazine.

November 2006: The city contracts The Army Corps of Engineers to provide shoreline study of area. This study will be used as part of the city’s report on alternatives for the Waikiki War Memorial Natatorium site to be completed by Wil Chee Planners. The $300,000 appropriation is approved by the City Council in December 2006.

2007: Army Corps of Engineers begins shoreline study.

July 2008: Army Corps of Engineers releases study of alternatives.

February 19, 2009: At his State of the City Address, Mayor Mufi Hannemann restates his intention to demolish the Natatorium pool. He promises to convene a working group to study options.

Summer 2009: Mayor convenes a Task Force to review the alternatives to the Natatorium’s site and states preference for demolition and rebuilding a replica of the entryway either in Kapiolani Park or elsewhere on island. Majority of Task Force members recommend this scenario. The Mayor accepts the Task Force’s recommendation of his preferred alternative.

2012: Gov. Neil Abercrombie proposes a plan to create a beach volleyball facility. Emails published online at Honolulu Civil Beat show that city and state officials had purposefully left the public unaware of what’s happening at the Natatorium. “What city officials apparently don’t want reporters or public to know is that hundreds of thousands of dollars in taxpayers’ money has likely been wasted on studies that are no longer needed,” reported Sophie Cocke in late September. Peter Apo of the nonprofit group, Friends of the Natatorium states, “We welcome Gov. Abercrombie’s initiative to reclaim the Natatorium.” “The issue of pool restoration or alternative use is yet to be addressed but we are relieved to be moving away from previous Mayor Mufi Hannemann’s public policy to demolish this national treasure.”