By Kiersten Faulkner, Executive Director, Historic Hawai‘i Foundation

As owners, stewards or development interests consider approaches to historic properties and cultural resources, they have the opportunity and responsibility to support appropriate preservation of these properties.

In many cases, a development or infrastructure project—whether done by a government agency or a private interest—has the potential to impact a historic property, either for good or for ill.

State, federal and local laws and regulations include processes that provide a systematic way to understand and address any potential harm. The process includes several basic steps:

- Define the project or undertaking;

- Define the geographic area of potential effect;

- Determine if historic properties are present;

- Determine if there is an adverse effect to those historic properties;

- Determine how to avoid, minimize or mitigate that adverse effect; and

- Document and execute the agreement.

This process may identify cases where a historic property will suffer an adverse effect from a proposed project. “Adverse” is a general category that indicates that the historic property will be diminished or harmed in a way that undermines its historic integrity or the characteristics that make it eligible for designation on the state or national registers of historic places. “Adverse effect” may include a continuum of effects that range from changes to context, inappropriate alterations, or complete demolition or destruction of the resource.

As Historic Hawai‘i Foundation participates in discussions about proposed changes that affect historic properties, HHF advocates for resolution of issues using a hierarchy of preferred actions. HHF’s priorities are to:

- Benefit the historic property through appropriate preservation treatment (preserve, restore or rehabilitate following appropriate standards and techniques), planning, use and operations.

- Avoid adverse effect on the historic property. Do not demolish, raze, relocate, inappropriately alter, or otherwise destroy the features and characteristics that comprise historic fabric, significance and integrity.

- Minimize adverse effect on the historic property. In cases where adverse effect to the historic property cannot be avoided, limit the nature of the impact to minimize the adverse effect.

- Mitigate adverse effect. In cases where the adverse effect is significant, measures to mitigate the effect should be used.

Sometimes, adverse effects to historic properties may be unavoidable to complete a project. In reaching decisions about appropriate mitigation, the property owner, government agencies and preservation stakeholders commonly weigh a variety of factors, including the significance of the historic property, its value and to whom, associated costs, and project schedules.

A plan for mitigating an adverse effect is site-specific and requires a particular approach for each historic property impacted by the project. Mitigation measures may vary widely depending on the type of historic resource, the qualities that make the property historically significant, the location of the site with respect to the project, the degree of impact, and other circumstances unique to the situation.

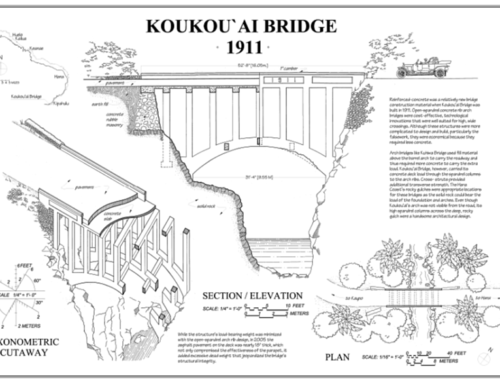

One common mitigation measure is data recovery—recording information about a property before it is destroyed by the undertaking. But many different creative mitigation approaches are possible. Mitigation should represent the broader public interest by providing knowledge, enhancing the preservation of other historic properties, or creating other beneficial outcomes.

When recommending mitigation measures in response to adverse effects on historic properties, HHF uses the following principles:

- Mitigation for adverse effects should have a nexus to the cause of the effect, such as connections between locations, type of historic resource, or type of impact with the proposed mitigation measure.

- Mitigation should be proportional to the adverse effect. Greater damage should result in greater mitigation, while minor effects can result in lesser levels of mitigation.

- Mitigation should have a benefit to the impacted parties (e.g. loss of a Native Hawaiian cultural resource should be mitigated by a benefit to Native Hawaiians; loss of a contributing structure in a district should be mitigated by a benefit to the district), and

- Mitigation should have a benefit to the larger public (e.g. improve understanding or education; provide new opportunities for preservation results; improve preservation systems to avoid future conflicts or losses).

- The goal is develop measures relevant to each site to understand, protect and celebrate its unique history, and to preserve the unique characteristics and significance for the current users and future generations.

Examples of mitigation developed for recent projects include:

- USDA Rural Housing Service Housing Project, Kunia: included an architectural inventory survey of the historic plantation camp and developing preservation plans that include maintenance, repair and design guidelines for historic structures and new buildings.

- Navy Region Hawaii Production Support Facility, Pearl Harbor: included preservation and adaptive reuse of five historic buildings and the deconstruction of an annex to one of the buildings; following preservation standards for rehabilitation of the existing buildings and design review for new buildings; salvage and reuse of historic windows and building materials; photo documentation and interpretive displays; and restoration of a historic feature within a reclaimed park.

- Hawai‘i Department of Transportation Farrington Highway Intersection Improvements, Nanakuli: included realignment and reconstruction of historic OR&L Railway tracks, and design and construction of an OR&L Depot Living Museum.

- International Marketplace Redevelopment Project, Waikiki: included preservation of exceptional trees and design to incorporate existing trees within the project; salvage, repair and re-installation of iconic entry sign; oral history project; interpretive displays on site; and publication of a book and website about the site history and context.